If there were a competition among non-Jews for the highest number of words written and spoken in defence of Israel since Oct. 7, it’s a safe bet British author and commentator Douglas Murray would win hands-down.

Admittedly, such a contest wouldn’t have an excess of contenders. Standing up publicly as a Zionist in recent months hasn’t exactly been a prescription for mass-appeal popularity—especially among the chattering classes.

But thanks to this topic, Murray now finds himself one of the most loved and loathed intellectuals in the English-speaking world. Despite being the object of vociferous criticism and physical threats, he isn’t easily deterred, not as long as there are people interested in his perspective.

Clearly, he has no trouble finding an audience, including a large, enthusiastic one on Feb. 28 at the Beth Avraham Yoseph of Toronto (BAYT) synagogue. Pre-registered attendees were only told of the location the night before for what was explained as a security precaution and to limit the possibility of anti-Israel protests.

For some, awareness of and interest in Murray owed something to his byline being inescapable in pro-Israel publications from the 195-year-old British publication The Spectator to Bari Weiss’s new journalism startup The Free Press, to say nothing of his many TV and podcast appearances. The author of seven books—several of them bestsellers—and the co-writer of two more, he’s long been in demand as a public speaker, with significant reach.

But for many Israel supporters, Murray first came on the radar last fall. Less than a week after the Hamas attacks on Oct. 7, a video of his speech at a British synagogue went viral. His heartfelt expression of solidarity proved almost therapeutic after the deadliest day in Jewish history since the Holocaust.

“They may come for Zionists,” he told attendees of an emergency panel discussion at the Lauderdale Road Synagogue in West London. “Very well, I am a Zionist. They may keep coming for the Israelis. Very well, I am an Israeli. they may continuously come for the Jews. Very well, I am a Jew.” He concluded the 10-minute speech with the words Am Yisrael Chai.

Since then, Murray’s public support of Israel has included multiple written dispatches from the Jewish state, frequent television appearances and social media posts, and in-person events like the one in Thornhill, Ont. As the war rages on, he’s continuously fielding requests to express his views, which he never seems to tire of sharing.

A bone-chilling night in Toronto gave Murray another stage to show his command of current events during a 90-minute Q&A session, which also served as a fundraiser for Tafsik, a new local Jewish advocacy association, whose name is derived from the Hebrew demand that someone stop how they’re behaving.

Before that, he gave The Canadian Jewish News an exclusive interview, while seemingly impervious to jet lag from a flight from Israel that arrived earlier that day. On the third floor of the synagogue, in a small anteroom, seated at a desk in a white shirt and casual blue suit, Murray looked younger than his 44 years.

Outside the door, in the hallway at the BAYT, two stern-looking, beefy bodyguards stood at the ready to keep the uninvited at bay.

Security is a going concern for Murray who’s long been the target of regular death threats from those angered by his opinions. Even before Oct. 7, he was a lightning rod for fierce controversy over statements criticizing Europe’s immigration policies, particularly what he deems a dangerous threat from Muslim immigrants.

“I’ve got to be careful about this,” says Murray, when asked about how he stays out of harm’s way. “I never talk about my personal security status but let’s just say I make sure I’m safe.”

And, whatever threats arise, he’s unintimidated.

“I don’t fear for my life,” Murray adds matter-of-factly. “But as for my critics and haters and so on, there’s a great line in Hamlet, where Hamlet says at one point, ‘Let Hercules himself do what he may, the cat will mew and dog will have his day.’ So I say, let the cats mew. You have several choices in life. One of them is to stand by your convictions and another is not. And I don’t regard ‘not’ as being an option. So I walk through any fire.”

Murray was in New York when he first learned of the invasion of Israel on Oct. 7.

“The next day, I went down to Times Square, where there was a so-called pro-Palestinian rally, which, of course, was a rally celebrating events in Israel the previous day,” he recalls. “So I already got an intimation, ‘Ah, we’re in that terrain.’ And I immediately thought I had to get to Israel as soon as I could. I knew I needed to see with my own eyes what had happened. I had an early inkling, based on previous experiences, that we were going to quickly get denial.”

That wasn’t his only concern.

“I also knew the world was going to move past Oct. 7 very swiftly,” he adds. “I knew that from the headlines in the international media on Oct. 8, the focus was already shifting to what would be Israel’s retaliation.”

Murray rushed to Israel to bear witness to the horrific scenes of slaughter and devastation in the southern communities. He interviewed scores of survivors, wounded residents in hospitals and relatives of those who had been kidnapped at gunpoint and held hostage in Gaza.

Murray was no stranger to Israel, having been to the country about a dozen times before. His first visit was in 2006, to cover the Second Lebanon War.

“Even back then, what I saw with my own eyes was not what I was reading in the media,” says Murray, who had previously travelled elsewhere in the Middle East. “That discord between what you see and what you’re told in the media is a real trigger for me. That discrepancy really increased my interest in Israel, because I’d already suspected it had been wildly defamed and lied about. And if you’re a writer or journalist, you shouldn’t like lies. And I don’t.”

Born in London in 1979 to Christian Anglican parents, and raised in an apolitical home where he grew to identify as atheist, Murray devoted his first book to the life of a British writer and poet who was the lover of Irish poet Oscar Wilde. Bosie: A Biography of Lord Alfred Douglas, published in 2000, helped launch Murray’s career while he was still an undergraduate at Magdalen College at Oxford University.

Most of his books have been topical since then: The Strange Death of Europe: Immigration, Identity and Islam, published in 2017, The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity, published in 2019, and The War on the West, published in 2022.

From the perspective of what’s happened to Israel since his first visit, Murray laments how the country is often shackled by global pressure before it can score a decisive victory in conflict with the Palestinians—and the negative consequences that ensue.

“It seems to me intolerable that Israel should have to fight a war in Gaza every two to three years, and a war in Lebanon every 15 to 20 years,” says Murray. “No other country is expected to do that. It happens because Israel keeps on being forced to a draw. The only thing that has brought to the people of Gaza and Israel are endless rounds of the same stalemate wars.”

But he won’t speculate on how this one will play out.

“Is the current Gaza war the last one or just the latest?,” he asks. “And will the next war be the last Lebanon War or the Third Lebanon War? I think everyone should hope that it’s the last in each case. But Israel is treated differently than other countries. I was in Ukraine last year, and there’s very full-throated Western support for Ukraine, which I agree with. Nobody wants that war to end in a draw. The reason the West is arming Ukraine is so it can win. But Israel is always stopped before the moment of victory by international pressure.”

Murray is concerned the current war won’t prove more conclusive.

“At some point, the war has to end,” he adds. “That means not having a ceasefire, not allowing Hamas leaders to scuttle away into Egypt but rather allowing Israel to destroy the Hamas leadership. If that happens, then victory can be declared, Gaza can start being rebuilt, and we will move to the next phase.

“But if an increasing number of international figures get their way, all that will have happened would have been that Hamas will have been throttled somewhat, and then just before the point of death, they’ll be allowed to come back to life, which isn’t desirable. Israel should be allowed to win.”

He’s also skeptical about the Western-promoted solution to the conflict, judging it, at best, dangerously premature.

“I think it’s just not happening because it’s a false paradigm,” he says. “In Israel, it’s extremely hard to find anyone these days who still believes in the two-state solution. Gaza was given to the Palestinians in 2005 [after Israel left], and they basically had a state since then and look what they did with it. They could’ve made it a Singapore. Instead of building up, they built down and created tunnels and a terror infrastructure.”

If Murray was already doubtful about the two-state solution before Oct. 7, he argues the circumstances and conditions since then make it now even more illusionary.

“I see no reason why the Palestinians should be given another state but I think there could be a way of taking incremental baby steps,” Murray says, before adding acerbically: “I’d like to see the Palestinians given, let’s say, a kindergarten to run and see if they can avoid teaching children to slaughter Jews. Or maybe they could be asked to run a hospital and we could see if they cannot stockpile weaponry in it, and then we could build out from there.”

He maintains an uncompromising reality check is much needed.

“The idea that significant portions of the West Bank should be handed over to the Palestinians for a state is for fairies,” he insists. “It relies on a fallacy which Western leaders need to believe in to have some kind of hope. What they don’t realize is the paradigm they are pushing is one of the causes of conflict, this notion that nothing in the Middle East will be solved until there is a two-state solution.

“The Abraham Accords showed that you could actually go around the Palestinians to get regional stability and normalization. The reason Western leaders say what they say about the two-state solution is due to a willful desire to have something to hold on to, but they should be more creative.”

His interaction with Palestinians also leaves him downbeat about the prospects of peace anytime soon.

“Two things need to be said about the Palestinians of the West Bank,” says Murray. “I’ve spent a lot of time around all that area. Strategically, Israel can no more hand over the hills of Judea and Samaria [the West Bank] to any Palestinian Authority, whoever it comprises at the moment, than it can give the Golan Heights to [Syrian dictator] Bashar al-Assad. It’s a strategic vantage point. I was out there again last month.

“At night, it’s even clearer than in the day. When you stand in the West Bank and look at the hills and you see the lights of Tel Aviv, Haifa and Ben Gurion Airport, knowing what we know about the Palestinians, if they get a state, as they have in Gaza, this will all be under rocket fire, or the threat of rocket fire, which is totally unacceptable.”

More sobering, according to Murray, is the support Hamas enjoys in the West Bank.

“The other reason for my doubts is due to what too few Western leaders are willing to accept,” he adds. “If there was an election tomorrow in the West Bank, Hamas would win it. So what does this tell us? It tells us we would have a terrorist state in the West Bank as well. Until the Palestinians can not produce such a terrorist state, they have no right to a state.”

Murray is similarly forthright in addressing antisemitism, especially its surge during the past five months.

“We all know that antisemitism is a light sleeper,” says Murray, who has many Jewish friends. “It wasn’t exactly dormant before Oct. 7 but since then it’s had kerosene poured on it. There are several reasons. With some of those who hate Jews, you can recognize them very easily. If somebody’s waving a placard celebrating the Oct. 7 massacres, you can say this as an antisemite.”

He’s quick to point a finger at the main sources of anti-Jewish hate.

“There are several main types of virulent antisemite in the West,” says Murray. “One is from recent Muslim immigration, which nobody in power ever wants to talk about. But if you import people from a culture which has a big antisemitism problem, you will get more antisemitism.

“Nobody needs to take my word for it. A very close enemy of mine, Mehdi Hasan, formerly of Al Jazeera and MSNBC, wrote a column 10 years ago in the left-wing New Statesman magazine, in which he said, if Muslims are honest with themselves, they know that ‘antisemitism is our dirty little secret.’ It’s always there. I believe him. He’s a Muslim. I’ve heard this from others as well. For example, many people from Pakistan, where almost no Jews live, come as immigrants with a very virulent hatred of Jewish people.”

And the hatred reaches far and wide.

“I remember being in Cairo and once entering a bookshop in the train station,” Murray recalls. “It was pretty hard to get the latest novels but very easy to get [Hitler’s] Mein Kampf and other antisemitic books like The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. That’s always been a swamp in the Middle East and in the Muslim world and it’s something they should address and stamp out. But they won’t address it until people call them out on it, but too few people do, as we’ve seen in the British government and others.”

For him, the left is also a culprit.

“Left-wing antisemitism is another main driver,” says Murray. “It became acceptable as right-wing antisemitism stopped being acceptable. Left wing antisemitism is based on a whole range of things, but one is the stupid narrative we’ve all sucked up from American campuses, which is that the world can be understood by looking at oppressor and oppressed, colonizer and colonized, perpetrator, victim and all this sort of thing. They apply that to the Middle East and lots of them get really hot because they can use that as their way to get the Jews.”

The third group is less easily labelled.

“In some ways, these antisemites are the most interesting,” Murray explains. “These are the ones who have been led into this and don’t know what fever swamps they are inhabiting. This includes many university students and others who like to think they have oriented their sense of social justice toward being anti-fascists, anti-Nazi, anti-racists,. They should pray to God they never get what they’re campaigning for because if they ever did get the Jews out from the river to the sea, they would discover they had become what they were trying to be against—the Nazis, finishing the job of Hitler.

“Those people are very misguided but they’ve been led into that by ignorance, malice, and much more. I hope they can be educated out of the evil they have been educated into.”

But for all his writing and speaking about issues tied to politics, Murray harbours little ambition to run for office.

“Any party that had me would find that on day one, I would speak my mind, and on day two, I would lose the party whip,” he says, laughing. “That doesn’t strike me as something attractive. Things would have to shake up radically in my own country before I’d even consider entering politics. I think that all of our countries in the West are in a very perilous position at the moment, with such a gap between politicians and the public.”

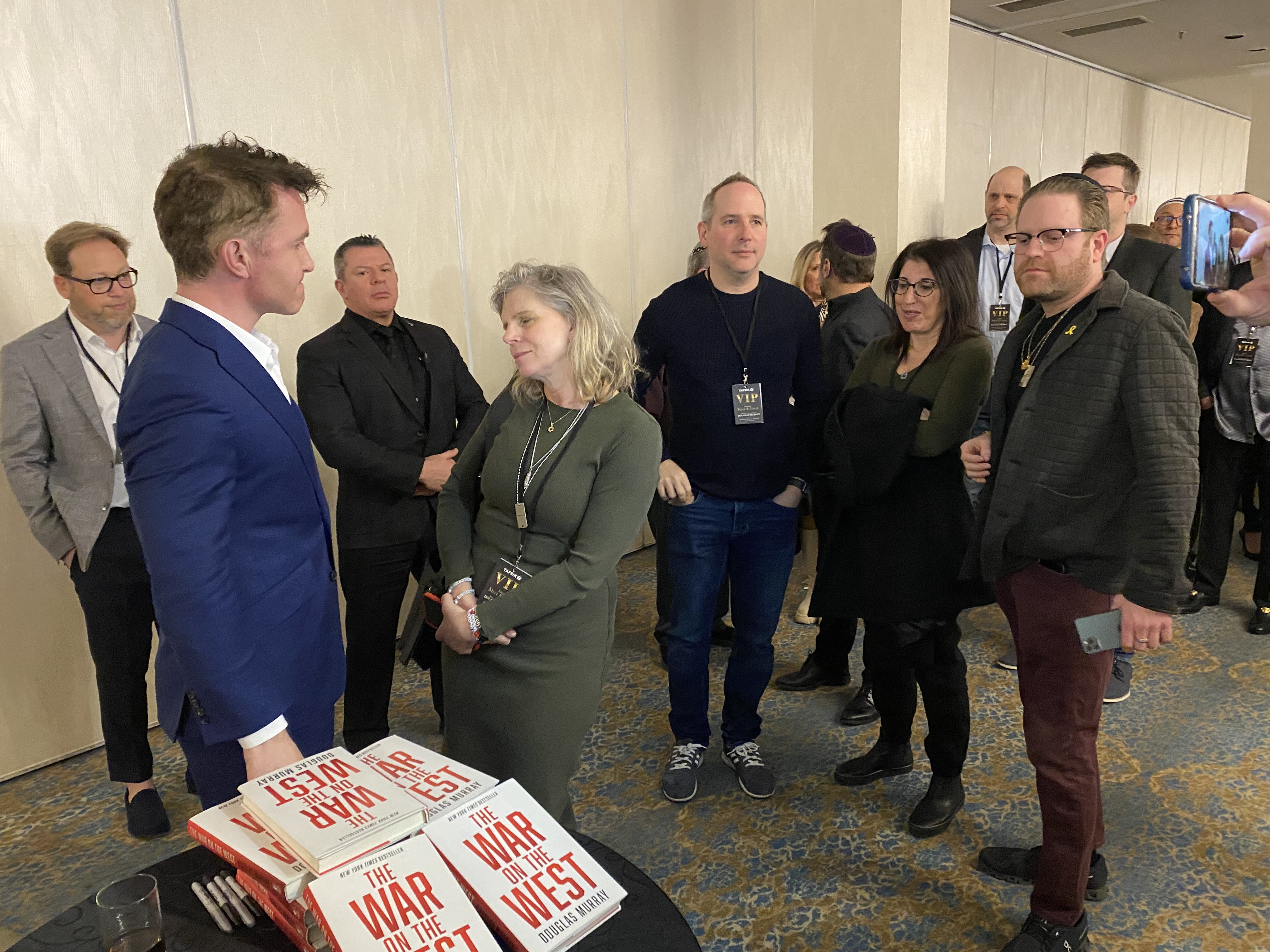

Following the interview, and before the main event, Murray descended one floor—accompanied by a bodyguard—to a VIP reception where he was warmly received by the exclusive crowd. Copies of his most recent book, The War Against the West, were on sale, and he personally signed them for guests. True to his affable manner, he cheerfully agreed to pose for selfies with them.

The feature presentation took place in a large room before a sold-out, mostly Jewish audience, which organizers said numbered 1,200—eerily about the same number of people slain by Hamas on Oct. 7. The crowd repeatedly broke into emphatic cheers and applause, as Murray delivered what they wanted to hear while speaking with astute conviction, even if he’s said the same things countless times before.

Given his steadfast and outspoken support for Israel, it’s clear to see how he became the darling of audiences there, too. He notes that his Israeli friends suggest that’s where he should actually be running for office.

“It means a lot to me,” he says. “I’m enormously moved but saddened by it because I think it’s a reflection, in part, of the fact that a lot of Israelis and Jews feel alone, that they don’t have many friends around the world. I hope it’s not the case.”

Murray says his personal philosophy is to “meet with triumph and disaster and to treat those imposters just the same,” a quotation from the 1895 poem “If” by Rudyard Kipling.

“I find that with praise and attacks,” he says,” “one can’t listen too much to others—you have to march to the beat of your own drum.”

Robert Sarner is a veteran Toronto-based journalist who regularly contributes to The Times of Israel and currently works as Senior Writer and Editor at Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Center.