Canadians love our multicultural, fish-out-of-water stories. For Muslims, it was Little Mosque on the Prairie; for Koreans, it’s Kim’s Convenience.

For Jews – right now, anyway – it’s Schitt’s Creek.

Yes, the show is about Jews. No, it’s not overly explicit. But once you realize Schitt’s Creek – which debuted its third season on Jan. 10 – is about Jews, you’ll never watch Schitt’s Creek the same way again.

READ: HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF IN TRANSPARENT

While the CBC comedy is ostensibly about a family of former one percenters, the Roses, who lost everything except a town they bought as a joke and now have to live in called Schitt’s Creek – which seems eye-rollingly improbable until you remember Saskatchewan’s own “Land of Rape and Honey” – it feels, at times, as much about the Jewish-goyish divide as the chasms between the urban and rural, or rich and poor.

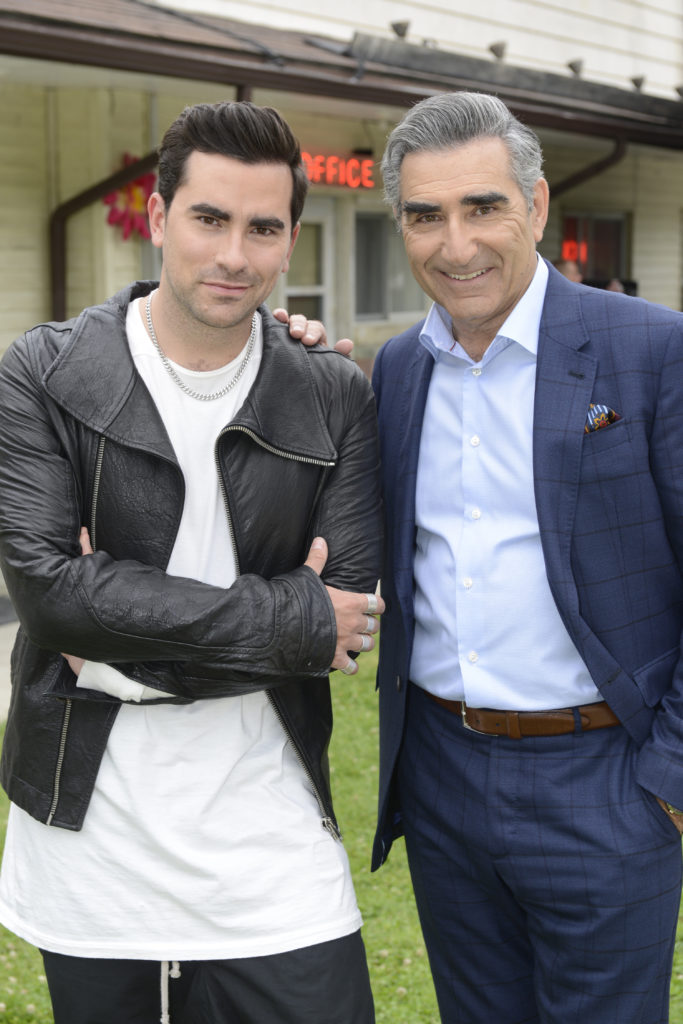

If it wasn’t immediately clear that the family is Jewish because it stars Eugene Levy and his equally-well-endowed-with-eyebrows son, Daniel (who is also the program’s hip, millennial showrunner), the writers made the good call of quietly pointing it out in a second-season episode about bagels.

Eugene Levy’s Mr. Rose, you see, is looking to kickstart a new business in this small town and needs an idea. He flippantly uses a bagel shop as an example, and an endearingly earnest neighbour takes him seriously, urging him to open the bakery.

“You’d still have considerable overhead,” Rose says, explaining why it’s a bad idea. “I mean, you’d want to make sure you’re making good bagels the real way.”

“Well,” his friend laughs, “you’d certainly know how to make them the real way, because you’re, uh…”

Rose finishes his sentence: “Jewish?”

“I didn’t know if I could say it,” the friend laughs. He later asks, “What’s the one you can’t say?”

‘Schitt’s Creek… is fundamentally about people who are uncomfortable around each other: Jews and gentiles, urban and rural, rich and poor’

Any Jew who’s been to a small town that has no Jews (which is, I believe, most small towns) knows the feeling of being some gentile’s “first.” They are sometimes surprised and, in my experience, often excited to finally meet a real-life Jew. They wonder if the stereotypes are true. They assume we’re religious.

Schitt’s Creek’s treatment of Jews works because it’s fundamentally about types of people who are uncomfortable around each other: Jews and gentiles, urban and rural, rich and poor. None of those castes are mutually exclusive. We live in a society where one of those stereotypes bleeds into the other.

The narrative of Schitt’s Creek – which is, I would argue, more modern and intelligent than many critics give it credit for being – doesn’t attempt to break down any of these stereotypes. Indeed, it leans hard into them, drawing out the idiotic nature of every character equally.

READ: FIND ME A JEWISH WOMAN WITHOUT BODY IMAGE ISSUES

Rather, the show embraces everyone’s idiocy and creates a world where every idiot has to live together. The Roses don’t get more rural or anything. They just find a way to be themselves while adapting to a new environment. (Remember how they’re Jewish?)

To be clear, Schitt’s Creek is not great TV. I generally watch it when I’m cooking. I once tried to sit down and watch it when I wasn’t cooking and did not enjoy it nearly as much. The jokes are overlong and the writers bank on awkward cringe comedy, particularly with Catherine O’Hara’s haughty matriarch, that only sometimes tracks.

But the acting is delectable, particularly by the younger Levy and Annie Murphy, who plays his sister. (Levy’s real-life sister, Sarah Levy, plays a waitress, which sounds like a snub until you see that she is also very well cast.) The comedic timing is generally there, and the subtle music cues and sparse opening shots help establish the show’s unique deadpan style, which is a relief in the CBC universe.

But more than any of that, it’s funnier than a lot of CBC comedies. Then again, maybe I’m only saying that because, in this case, I’m seeing myself as the little one on the prairie.

Author

Michael is currently the director of The CJN's podcast network, which has accumulated more than 2 million downloads since its launch in May 2021. Since joining The CJN in 2018 as an editor, he has reported on Canadian Jewish art, pop culture, international travel and national politics. He lives in Niagara Falls, Ont., where he sits on the board of the Niagara Falls Public Library.

View all posts