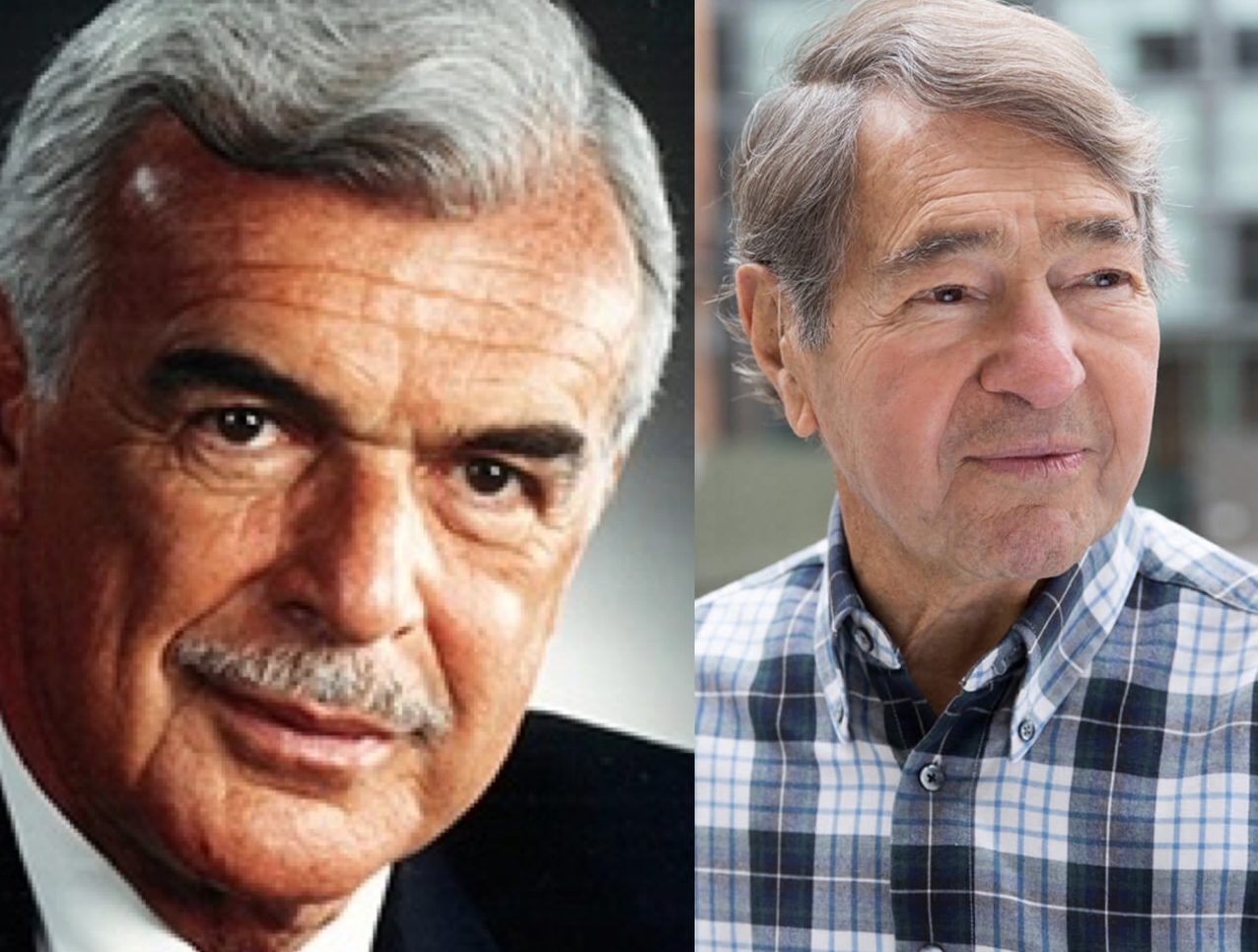

The two “Jacks” who played seminal roles in building modern Toronto—and who died within a few days of each other in October 2022—had much in common despite different personas.

Jack Diamond and John “Jack” H. Daniels were both Jewish immigrants, and a family history of persecution influenced their destiny. They became architects—a field in which Jews of their generation were sparse.

The first Jack attained international stature in that profession’s design side, while the second Jack was a builder, making a success in real estate.

Over their long lives Diamond and Daniels changed the landscape of Toronto—literally and figuratively—and leave an imprint that will last for generations.

Although different in temperament, each was an activist and ahead of his time in envisioning a more livable city and equitable society.

Abel Joseph Diamond, who died on Oct. 30 just shy of his 90th birthday, was born in South Africa into a family from Lithuania where Diamond’s grandfather was murdered in a 1917 pogrom.

Daniels, who was 96 when he passed away on Oct. 22, left Poland in 1939 at the age of 12, his family fleeing looming Nazism.

Among Diamond’s numerous achievements in Toronto are the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, Corus Quay, St. Michael’s Hospital and Holy Blossom Temple, and, elsewhere in Canada, Montreal’s Maison Symphonique and the University of British Columbia medical school.

Internationally, he designed Israel’s foreign ministry building and the Jerusalem City Hall and the Mariinsky II opera and ballet hall in St. Petersburg, Russia. One of his last projects was the United Kingdom Holocaust Memorial in London in 2016, in Victoria Tower Gardens near parliament.

After studies at the University of Cape Town and Oxford, Diamond began his practice in South Africa. He then taught at the University of Pennsylvania and, working with the towering Louis Kahn, in 1964 he established the Master of Architecture program at the University of Toronto.

Early on in his new home, Diamond made his mark as an urban planning reformer, urging the revitalization of older neighbourhoods and warning against suburban sprawl, an expertise the Ontario government would call upon in the development of the Greater Toronto Area.

Diamond was outspoken about the necessity of investing in public housing and transit.

His colleagues at Diamond Schmitt eulogized him as “one of the most significant and defining architects of his generation” and “a teacher, collaborator and mentor who shaped an exhilarating studio culture” who helped launch the careers of many architects in Canada and abroad.

Partner Don Schmitt said Diamond’s experience living in an apartheid regime was at the root of his commitment to equity. He was an Ontario Human Rights Commission appointee.

Diamond was a talented watercolourist, a lover of classical music serving as a trustee of the Canadian Opera Company, and appreciated good food. A peccadillo of his was having a soup made from scratch every day at his office by staff and himself—his way of fostering collegiality. Diamond was proud that his was the only architectural firm ever among Canada’s 50 best-managed companies.

The other Jack, who most notably built the Toronto Eaton Centre and Toronto-Dominion Centre, also had a strong social conscience, championing higher education and affordable housing.

The John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design at the University of Toronto (UofT) speaks to its benefactor’s long support for his alma mater. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in architecture in 1950.

He and his wife Myrna gave more than $30 million to the UofT, which transformed architectural education, quadrupled enrolment and raised the department’s international stature.

Starting in 2008 they donated $20 million for scholarships to gifted but needy architecture students, prioritizing those who are the first in their family to pursue post-secondary education.

Five years later they gave $10 million for a new home for the architecture school, incorporating spacious new facilities into a renovated 19th-century heritage building.

In total, Daniels and his wife gave over $200 million to educational, health care and cultural causes. One of his earliest interests was Associated Hebrew Schools of Toronto, where his father taught. The younger Daniels was its architect and fundraiser.

“A celebrated innovator in urban development, John was guided by a strong social conscience rooted in his own experience as an immigrant to this country,” said UofT president Meric Gertler.

As a high school valedictorian in 1944, Daniels expressed the ideals that would guide him: “Canada will be a home for many millions of peoples and many different races and creeds. Let us realize we are all Canadians and pride ourselves with more community consciousness.”

Daniels made his first foray into real estate development while still at UofT, building a few houses with borrowed money. He would go on to become CEO of the Cadillac Fairview Development Corporation, one of the largest real estate companies in North America.

In 1983, he left Cadillac Fairview to start the Daniels Corporation, which was behind numerous residential projects in Canada, including Erin Mills in Mississauga. The business worked with government to build thousands of non-profit rental units, founded the First Home communities geared to first-time buyers, and revitalized Toronto’s deteriorating Regent Park public housing project.

The Danielses were early investors in the Toronto International Film Festival in 1976, supporting the Bell Lightbox Theatre. Earlier, he was a founder of the Toronto Sun newspaper.

“John was a ‘city-builder’ long before the phrase became popular,” said Richard Sommer, former UofT dean of architecture. “He had a humility that could belie the sharpness of his intellect, his uncompromising will to excel, and his array of accomplishments.”