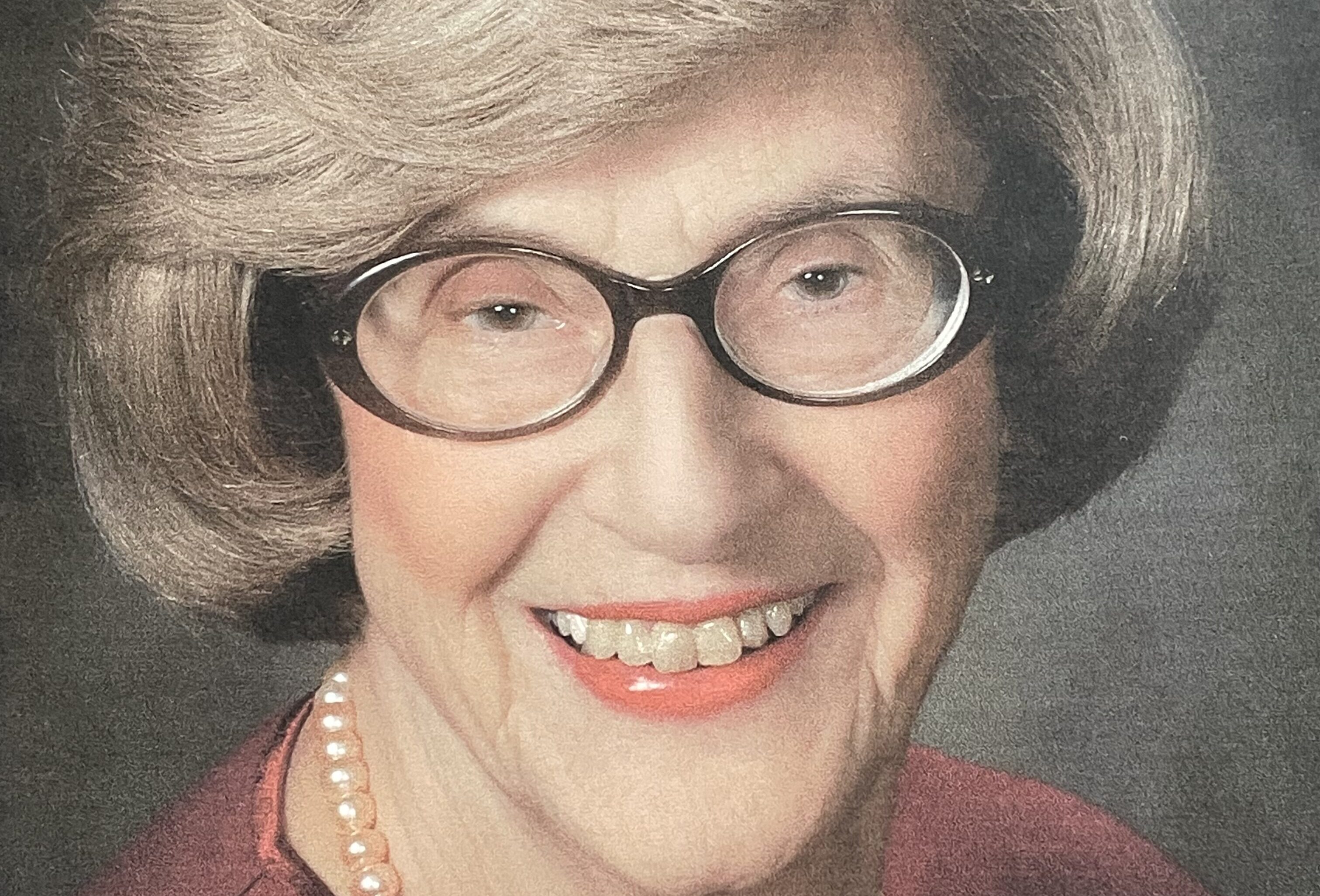

Lita-Rose Betcherman, a pioneer for women’s rights in Ontario and author of The Swastika and The Maple Leaf—the first book to explore the rise of the far-right and antisemitism in Canada died on March 9, two days after her 97th birthday.

Her pursuit of knowledge at a time when women who attended university were an anomaly gave her a unique perspective on women’s rights and fueled her passion for researching and writing—a second act in an already extraordinary career.

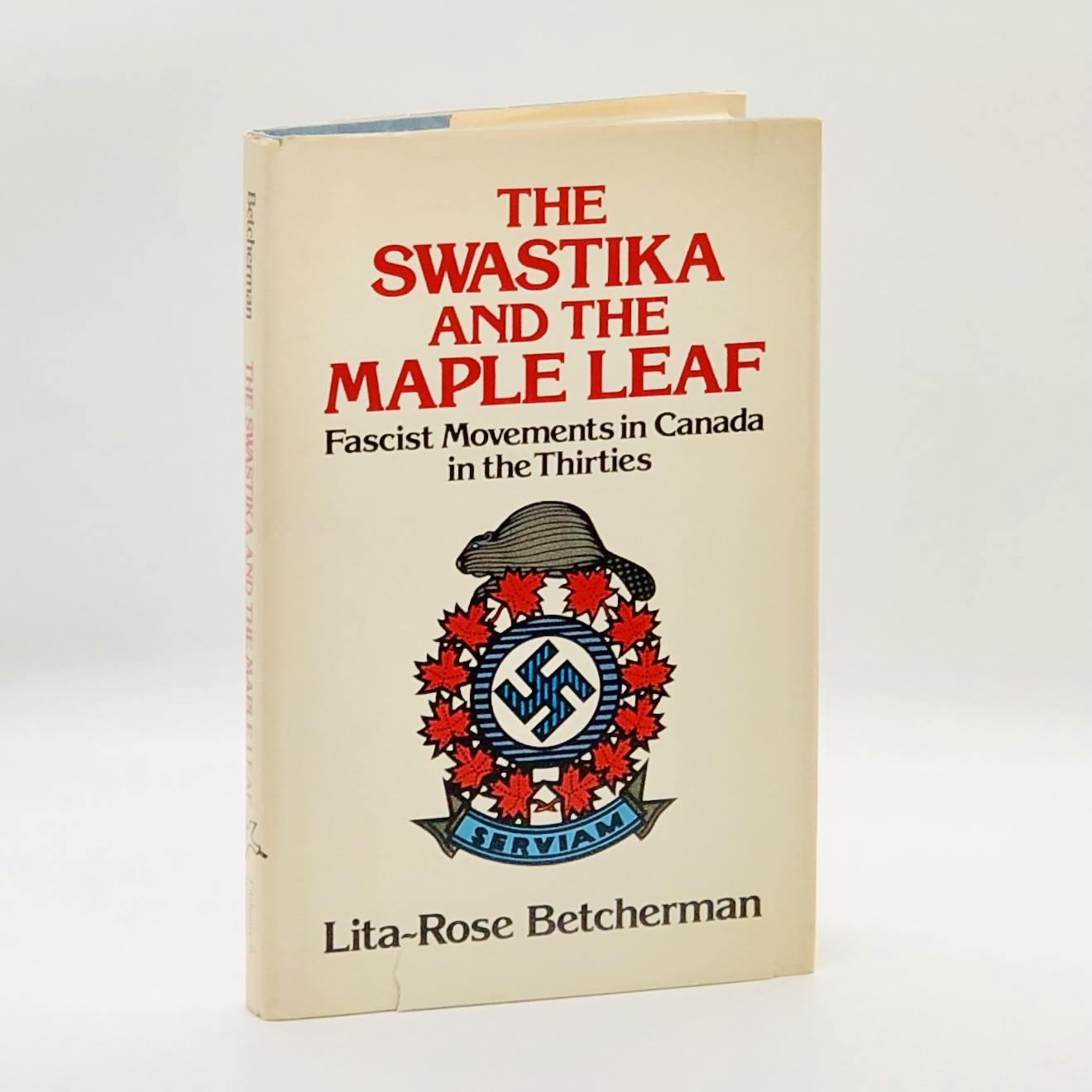

The Swastika and the Maple Leaf: Fascist Movements in Canada in the Thirties, her first book, was published in 1975 and revealed a dark period in Depression-era Canada when the fascist party in Quebec although considered fringe, was still influential.

“Our native fascists were not idealists. They were not anti-communists. They didn’t want a corporate state like Mussolini. Ours were antisemites,” Betcherman explained in an interview following the book’s publication. “And, they became influential in Quebec even before Hitler came to power.”

Betcherman was born in Montreal in 1927, and her family had first-hand experience with the movement. Her Romanian-born father was a shopkeeper and lived through the “Achat Chez Nous” campaign—an attempt by church and nationalist leaders in Quebec to institute a boycott of all foreign businesses—particularly Jewish owned ones in the province.

“Every Sunday the priest would foment against ‘The Jew’. Thankfully his parishioners were disobedient and walked out of church and into my father’s shop,” Betcherman said following the book’s publication.

When she was three years old, her family moved to Ottawa where her father, Joseph Vineberg, purchased Larocques’ department store, a fixture in Ottawa until the 1970s.

As a teenager in Ottawa, she first met her future husband Irving, then later studied history at the University of Toronto at the same time as him. They were married, returned to Ottawa and while she was raising four children she was appointed president of the Ottawa chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women and president of the Citizen’s Committee of Children. She then returned to Carleton University where she obtained an MA in 1962.

The family moved to Toronto and Betcherman returned to academia where she graduated from University of Toronto with a PhD in history despite the discouragement of her professor who expressed dismay that a woman in her 30s would pursue a PhD. “She was told to her face, don’t bother, you’re a woman,” her son Gordon Betcherman told The CJN.

Then she started her professional career. Ontario was the first province to create a Women’s Bureau at the Department of Labour in 1963 and Betcherman was their second director from 1966 to 1972.

She was the public face of the Women’s Bureau, advocating for equal working conditions and addressing pay discrimination. “She was the bureaucrat responsible for developing policies that the government put into place,” according to her son.

“It was a very invigorating time when women were just starting to make their way up in the labour force. It took a long time to change attitudes. And women themselves had been brainwashed into taking any job—usually as a secretary—while men would hold out for a good job. Part of my work was to raise women’s expectations for themselves,” she said when she left the Bureau.

Betcherman played a key role in passing the Women’s Equal Employment Opportunity Act which ensured women were given the same job opportunities as men, entrenched maternity leave as a right and banned job ads that limited positions to applicants of a specific sex.

After she left the Women’s Bureau, she was an arbitrator for nearly two decades dealing with disputes between labour and management. In addition, she served on the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the Ontario Press Council, and the Ontario Judicial Council.

Former Supreme Court Justice Rosalie Abella met Betcherman when we they were both on the Ontario Human Rights Commission in the 1970s, and shared her memories with The CJN.

“I became an ardent admirer instantly. I’d known of her pioneering work as the director of the Ontario Women’s Bureau. I also knew about how wonderful she was from my husband, who was working on his PhD at the same time she was at University of Toronto.

“Over the decades, we stayed close with her and her extraordinary family and our love and admiration for all of them grew the more we got to know them and I was dazzled by her extensive labour relations expertise when she served on the Ontario Labour Relations Board with me.”

By the 1980s, Betcherman was ready for a change. And ironically, she recognized that her work within the government agencies was limited—because she was a woman.

“My mother had incredible energy. At the same time that she was working as a labour negotiator, she started her writing career,” Gordon Betcherman said.

Although her PhD was on 17th-century British history, she decided to focus on Canadian history. She had written articles in academic journals and art magazines, but The Swastika and the Maple Leaf was her first book.

“What struck me was the depth and exhaustiveness of her research,” son Gordon said. “Her books were based on doing primary research on sources that no one else had gone through before. She had an ability to take all that material and tell a story that was much more accessible than purely academic history.”

Mordecai Richler described The Swastika and the Maple Leaf as, “A lively, readable history, the stronger for being detached and allowing the embarrassing facts to speak for themselves… It is strong , evocative stuff, a necessary reminder of how things were.”

Abella said in an email to The CJN that her late husband, Canadian historian Irving Abella found it “courageous and pathbreaking”.

As a counterpoint to The Swastika and The Maple Leaf, Betcherman published The Little Band: Clashes between the Communists and the Political and Legal Establishments in Canada, 1928-1932 in 1982.

Ernest Lapointe: Mackenzie King’s Great Quebec Lieutenant followed in 1982 and Court Lady and Country Wife: Two Noble Sisters in Seventeenth Century England was published in 2005.

Her husband of 65 years, Irving, who died in 2012 was her constant supporter.

“My dad was pretty enlightened for a Jewish businessman of his generation. He had a PhD himself, so he was oriented to the idea of research and career development. There was no culture shock for him when she got into this. He didn’t expect her to be a stay-at-home housewife,” Gordon said.

Throughout her life Betcherman was a strong supporter of the Jewish community both in Ottawa and in Toronto.

“She was exceptionally brilliant, generous, intellectually elegant and wise, and never lost her intrepid and humane spirit. I adored her,” Rosalie Abella said.

Lita-Rose Betcherman is survived by her sons, Michael, Gordon and Martin; grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She was predeceased by her husband Irving and daughter Barbara.