When Cantor Moshe Kraus of Ottawa died, on May 29 at the age of 100, he had been carrying a grudge for almost 80 years.

It was a grudge against himself.

Kraus, who was born in what was then Czechoslovakia in 1923, wound up in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp during the war. He survived because of his voice. Commandant Josef Kramer, who was nicknamed the Beast of Belsen, took a liking to Kraus’s singing. He made the young cantor perform for him every Sunday, which ensured Kraus remained protected.

The first time Kramer brought in Kraus to sing for him, he requested a German song by the renowned Jewish tenor Joseph Schmidt, whose style Kraus imitated.

“I sang it, and unbelievable, he cried. I couldn’t believe it, he can cry,” Kraus recalled in an interview from 2016 with Carleton University.

It was so unbelievable to Kraus because Kramer was so exceptionally callous otherwise.

“That murderer, that nothing–I don’t have the words—‘murderer’ is a compliment for him. For him, killing a person was like killing a fly,” he said in a Yiddish-language interview with the Yiddish Book Center from 2019. “If he was going for a walk and saw a Jew, he would shoot him. He would go to see if the bullet hit right in the middle (of the forehead). And if it wasn’t in the middle, he said a very nasty word.”

Kraus was baffled by the incongruity of the man who used Jewish lives for sport on the one hand yet could be moved to tears by a Jewish man singing for him on the other. And he was also baffled by his response when he learned of Kramer’s death by hanging in 1945, which became the source of that grudge against himself.

“When they hanged him, I cried. He saved my life,” Kraus tearfully recounts in the Carleton interview. “And I can’t forgive (myself) till today why I cried.”

Kraus’s talent didn’t just save his own life. He was granted permission to sing for prisoners at the camp, boosting their spirits. According to the description of his memoir, The Life of Moshele Der Zinger: How Singing Saved My Life, “many Bergen-Belsen survivors remember him as ‘Moshele der Zinger’ (Little Moshe, the singer), whose beautiful tenor voice and trove of Yiddish and sacred music had kept their hopes alive—and in many cases restored their faith—during the living nightmare of the Holocaust.”

Before the war, Kraus was trained as a cantor. When he was as young as nine, he would travel across Eastern Europe, leading services for Shabbat in various Jewish locales. After his bar mitzvah, he became even more sought after. By his early teens, he was making lots of money for his family–parents Myer and Henya and his eight siblings. Both of Kraus’s parents and five of his siblings were murdered in the Holocaust.

After the war, Kraus ended up in Bucharest, Romania, to serve as the Malbim shul’s chief cantor. His next stop was in Germany, where he worked for the Joint Distribution Committee, and then to what was then Palestine, where he became the first chief cantor of the Israel Defense Forces.

“There were so many funerals and memorial services to attend. I cried for the young soldiers who died defending Israel, and at the same time I shed many tears for my own immense losses,” Kraus told Mishpacha about his time in the IDF.

It was also in Israel where he met his wife of 72 years, Rivka. As soon as he saw her, Kraus knew that he wanted to marry her. They met at a crowded wedding with thousands of people, so big that it had to be held outside. The friends of the bride and groom brought food around to the guests. As a friend of the bride, Rivka, who was 16 at the time, was helping.

“And when I saw her–she was very beautiful. You can see her today, she looks like she’s 30. She’s 83,” Kraus said in his Yiddish interview. “I went over. I talked with her for half an hour. And after half an hour, I said, ‘Rivka, will you marry me?’”

Instead of immediately accepting his proposal, Rivka called him crazy. But he persisted. He would go to see her every day, and eventually she agreed to marry him.

After Israel, Kraus’s next stop was as chief cantor in Antwerp, Belgium, and then in Johannesburg, where he came face-to-face with his past.

“When I arrived in Johannesburg and became the chief cantor… I didn’t know English, so they brought a woman who speaks Yiddish that she should greet me… I go to her and thank her, I tell her how happy she made me with her speech,” Kraus said in the Carleton interview. “And she says to me, ‘you know, you remind me of Moshele the singer in Bergen-Belsen. I was in Bergen-Belsen, I remember a man came to sing for us, and he sang like you. Very similar.’ And I said to her, ‘I am Moshele the singer.’ She fainted. They brought her back, she was crying, I was crying.”

During this time, in 1964, Kraus was asked to travel behind the Iron Curtain for a three-month concert tour. Leonid Brezhnev, who led the Soviet Union at the time, wanted a Jewish act to show the world he wasn’t antisemitic. Aside from the danger of travelling across the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War, Kraus and Rivka were also asked to free some Jewish refuseniks. At one point, Kraus had to shake off his tail to carry out an undercover action. (Mishpacha magazine published a story with more details in 2017.)

The Krauses moved from Johannesburg to Mexico City, and finally settled in Ottawa, where they lived for the last 50-odd years. Kraus became a vital part of Jewish life in the city, said Heshel Teitelbaum, president of Ohev Yisroel, the shul where Kraus had been a member for the past 20 years.

Teitelbaum first met Kraus around 45 years ago, when Teitelbaum moved to the city for a teaching job at the University of Ottawa. When Teitelbaum first arrived, he knew nobody. He attended a service at Beth Shalom, where Kraus was cantor at the time.

“He immediately invited me to his home. He didn’t know me, just a stranger, but it made a big impression,” Teitelbaum said. “When hazzan Kraus did this, I said, ‘wow, I feel really at home here.’ So I got to know him, he invited me, and later, my wife to his home for shabbos. It made a fantastic impression.”

The rest of Teitelbaum’s family got to know the hazzan as well. Kraus once told Teitelbaum that he had only taught three people in his life, despite many requests from would-be cantors. However, Kraus decided that Teitelbaum’s son had a talent, so he decided to be the young boy’s teacher as well.

“When you’re standing in front of a man with such presence, you kind of feel a little bit intimidated. And my eight-year-old son, he would also feel intimidated,” Teitelbaum said. “Not that he was threatening him. But he would make one slight mistake, and the hazzan would let him know. But he stuck it out, baruch hashem… my son is a rabbi in Pittsburgh right now.”

“Still, you will get the impression that (Kraus) was extremely precise and wanted precision and no mistakes. And he made sure that my son would not make mistakes.”

It wasn’t just with his students that Kraus could be intimidating and demanding. Teitelbaum described Kraus as possessing “an apparent lack of tolerance for people who didn’t do things right.”

“He wanted perfection, not only from himself, but he wanted perfection from others. So sometimes, for example, I, the gabbai at shul, would be a little bit trembling because if I made the slightest mistake, he would let me know.”

Kraus always carried himself with dignity and authority, and that contributed to his imposing presence, Teitelbaum added.

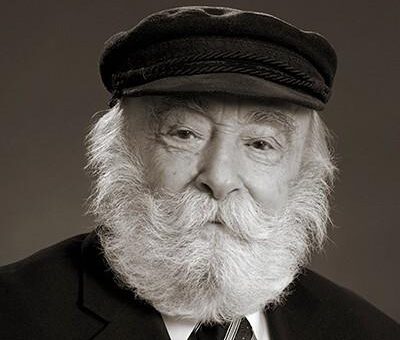

“He was a real personality. He would stand out in a crowd. First of all, he is short by stature. So you wouldn’t think that he would stand out. But he had a presence, he had an attitude. He was dressed impeccably, tailored suits. He was groomed impeccably, with his twirly moustache and his beard always trim. He was dressed royally, he would walk with a demeanour like he was a prince or something, so he would stand out.

“And his facial expression would also contribute to that aura, so people would turn when he would walk down the street.”

The congregation of Ohev Yisroel feels so strongly about commemorating Kraus’s memory that they have begun work on a feature film about his life. Donations are being accepted to help fund the production.