First, a bit of movie trivia: what New York-born Jewish actor plays an Italian-American in love with an Irish immigrant plumber in what recent film? Hint: most of it takes place in 1950s Brooklyn. The answer is Emory Cohen, who plays Tony Fiorello opposite Saoirse Ronan’s memorable Eilis Lacey in the Oscar-nominated film Brooklyn.

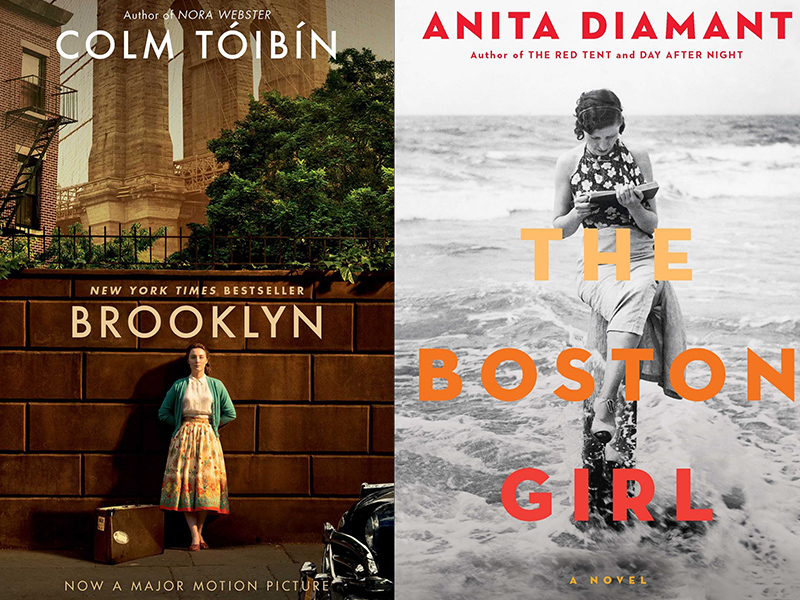

Scripted by Nick Hornby and directed by John Crowley, Brooklyn is closely based on Colm Toibin’s masterful novel of the same name, but actually improves upon a few key plot-points in the story.

Toibin’s Brooklyn, rendered with an Austenesque clarity and a satisfying depth beneath the pale outward forms of his characters, is a wonderfully realized immigrant saga involving the sleepy Irish coastal town of Enniscorthy and the bustling metropolitan New York suburb in the postwar era.

Immigrant sagas tend to make good literature and cinema, because their protagonists are shown making important decisions that affect not only themselves, but also future generations. They take or do not take the fabled road through a yellow wood, a turning that will make all the difference in their lives and those of their children and children’s children.

Another riveting family tale that stretches between Ireland and Brooklyn (and back to Ireland) is the bestseller Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, which, however, did not fare nearly so well on the big screen: in this case, the book is much better than the movie. I read Angela’s Ashes when it first appeared some 20 years ago, and its depiction of truly pathetic characters caught up in bleak fate made an indelible impression. Funny, that I think of it as a novel when it is actually an autobiography-memoir: these genres are close cousins that often seem to meld into one another.

Another bestselling immigrant saga – this time Jewish-themed – that also marks its 20th anniversary this year is The Color of Water, A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother, by James McBride. This, too, is an autobiography-memoir that is so powerful and so well put together that one might easily remember it as a novel.

The white woman referred to in the subtitle is the former Rachel Deborah Shilsky, who escapes an abusive Jewish home in Suffolk, Va. converts to Christianity, marries a black preacher, and has 12 black children by two husbands. As Ruth McBride, she never says a word about her own painful upbringing while her children are growing up. She tells them she is a “light-skinned” black when they ask why she is a different colour than they are.

“And God? What colour is God?” the children invariably ask.

“God has no colour,” she replies. “God is the colour of water.”

To their children, their energetic and faith-oriented mother is a mystery. Eventually her son, author James McBride, gets her to talk in depth about her early life. She tells him about her father, a mean-spirited rabbi and shopkeeper, and her mother, a passive, crippled woman with a heart of gold – Polish-Jewish Americans whose stories are heavily inflected with Yiddish and the flavours of the immigrant experience.

McBride’s well-crafted, uplifting and, at times, heart-breaking memoir switches in alternating chapters between his own voice and that of his outwardly ordinary yet tremendously inspiring mother. It’s true that Jewish characters are painted darkly here but, sadly, it’s all in service of the truth – at least as subjectively remembered by Ruth McBride and then filtered into narrative by her son.

Since its publication, The Color of Water has won numerous awards, been translated into 16 languages and sold more than 1.5 million copies. The book made Ruth McBride a celebrity, so much so that the New York Times published a feature obit on her when she died at age 88 in 2010. However, despite the book’s popularity, I don’t imagine that it would make a good film. Not every story can survive a transplant from the medium of literature to the medium of film.

Another memorable Jewish-themed memoir that fits into this company is The Invisible Wall by Harry Bernstein; its subtitle is “A Love Story That Broke Barriers.” Some 10 to 15 years ago, while in his mid- to late-90s, Bernstein wrote a remarkable quartet of memoirs, the first of which, The Invisible Wall, appeared in 2007, when he was 96. (Yes, there is hope for late bloomers who leave their literary aspirations to the last minute.)

Set in a Cheshire mill town on the eve of World War I, The Invisible Wall paints a grimly realistic portrait of his Jewish family, including a father who often drank and gambled away his wages. The Jews live along one side of a street in which an imagined barrier or “invisible wall” separates them from their Christian neighbours on the other side.

Bernstein narrates the story in the first-person as a young child. He recounts how his sister conducts a secret love affair with a Christian boy across the great divide and the immense ramifications of their dramatic Romeo-and-Juliet relationship. It’s yet another instance of how an episode from an ordinary family history can become the stuff of great literature.

A more recent title of note is The Boston Girl, a novel by Anita Diamant, author of the popular feminist biblical saga The Red Tent. The Boston Girl focuses on Addie Baum, a child of immigrant parents born in Boston in 1900.

Addie is an 85-year-old narrator who tells her story in the first-person as she looks back on her life. The book describes how a literary-minded American Jewish woman gets educated and finds her own voice and independence.

The Boston Girl is an impressive work, but one in which modern values and sensibilities somehow manage to seep onto the page. That is always the danger when a narrator looks back to a distant past: the sense of immediacy and authenticity may suffer as a result.