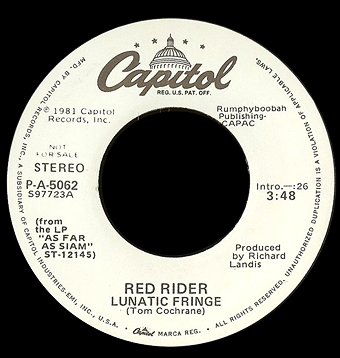

In the late summer of 1981, Toronto-based quintet Red Rider were climbing the pop charts on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border with the release of their sophomore record, As Far as Siam. The album’s lead single, “Lunatic Fringe”, would hover just outside the Billboard rock radio airplay top 10 as late as December of that year, on its way to becoming the band’s biggest hit, and achieving an undeniable place in Canadian rock lore.

Forty years later, Red Rider lead singer Tom Cochrane, a Canadian music legend in his own right, is getting ready to head back out on the road. “We’ll be playing again, making people smile, sing and think,” he says on the phone. “We just have to be careful” with COVID, he adds, which is why he and his band will be performing for crowds of maybe 4,000-5,000 instead of 12,000 or more in safer times. He is concerned about all the misinformation out there right now, and he sees how it is destroying lives and families.

Truth is, he’s been worried about that subject for a long time.

“I was a pretty good history student,” he explains, “and one of the most impactful things in my life for sure was the knowledge I got through reading writers like Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel.

“All through history, we see how violent people and regimes get their way by suppressing people and committing genocide. But nowhere in the modern era is it more obvious than what happened in Germany in the 1930s and ‘40s.

“These things happen when there is social unrest, economic upheaval—when people feel threatened and fearful about things. I think we always have to be mindful of that. It’s always lurking beneath the surface.”

Cochrane penned “Lunatic Fringe” at a time in his life when he was “one step away” from being engaged to a Jewish woman and, ever the history student, reading about the life of Raoul Wallenberg.

“I was very touched by his story,” he continues, “because here was someone who was struck so heavily by conscience that he had to do something to help. There have to be people who aren’t Jewish who speak out.”

In a sense, “Lunatic Fringe” was his response. The song, the first track on As Far as Siam, begins with a lone, eerie synthesizer. A high-pitched howl descends into a cacophonous growl, and then the guitars join in on a distorted, pulsing B chord. The subsequent note progressions suggest a fairly typical blues-rock orientation, but this is actually one odd song. There’s no discernible chorus, just a bunch of verses sung around a flashy keyboard sequence. One listen to “Lunatic Fringe” and you know something unusual is going on here.

From the opening line, Cochrane, a thoughtful songwriter one might generally expect to embrace the unknown (consider “Life is a Highway,” or even “White Hot,” about Arthur Rimbaud’s Africa travels), is defiant. He sounds absolutely certain of his position:

“Lunatic Fringe / I know you’re out there / You’re in hiding / And you hold your meetings / I can hear you coming / I know what you’re after / We’re wise to you this time / We won’t let you kill the laughter.”

After a brief, bluesy return to that B chord, Cochrane continues his assault on the Lunatic Fringe: “This is open season / But you won’t get too far / ‘Cause you got to blame someone / For your own confusion / We’re on guard this time / Against your Final Solution.”

A searing steel guitar solo later, Cochrane concludes: “Lunatic fringe / We all know you’re out there / Can you feel the resistance? / Can you feel the thunder?” as a siren wails in the background.

No one other than Cochrane wanted to release the song, but he prevailed. “I said for better or worse, it probably won’t get listened to, but this song is going out there. It needs to be heard.” And he was right: in 2009, “Lunatic Fringe” was honoured by the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada (SOCAN) for reaching the 100,000-airplay mark on Canadian radio.

What does Cochrane think of his song now? “I’m not proud of the fact that ‘Lunatic Fringe’ is probably as impactful now as it was back then, but the reality is that it is,” he admits. “These things are all tied together, and they spawn the lunatic fringe. And when the lunatic fringe starts to become the mainstream, that’s when the danger happens, and we’ve seen evidence of that of late.

“I’m very proud of the song as a piece of art, but art isn’t always pretty.

“‘Lunatic Fringe’ should be disturbing, but it should also be a cause for hope, because, like I say in the song, there are those of us out here that aren’t gonna let those things happen again. And you gotta speak out when you see injustice.

“It’s a song about standing up for what is right, so I’m proud of the song from that point of view, proud that I could say something.”

Yoni Goldstein is the CEO and Editor-in-Chief of The CJN.