In the famous Broadway musical, Hamilton, there is a very intriguing bit of advice: the author, Lin-Manuel Miranda, uses a potential opponent to warn Hamilton that he should “smile more, talk less.” This sounds like good counsel. In this day and age of open communication and social media, the idea of verbal restraint may be shocking, but it resonates with some of us.

Current norms of psychology seem to encourage self-expression. In many ways, we can view our social development as positively built upon that belief. We have come to understand that people should not lock up their thoughts and emotions. Public communication is also an essential element of our civilization: democracy is built upon the idea that individual citizens have a right to speak about public issues and that their voices need to be heard.

I am thus not advocating silence. I am not writing in favour of the adage: children (or women) should be seen and not heard.

But I am confronted with the possibility that there is too much talking and not enough listening. People rush to speak their minds without thinking about the appropriateness, or necessity, of such speech. In the classroom, we encourage students to participate – to ask questions, or pick up a point of discussion to elaborate on. But often times, I find that students will just open their mouths for the sake of hearing their own voices, even though they have nothing of substance to add.

In many social situations, people offer advice and opinions that are better left unsaid. I have heard so many comments at funerals, shivas and in hospital rooms that are not just tasteless, but downright insulting. Why can’t people just sit quietly at a shiva and allow their presence to signify their condolences? There is no need to speak, unless the mourner introduces a topic. That is actually the proper etiquette.

But it is in the realm of social media – of Facebook, Twitter and other sites – that the propensity for full disclosure overwhelms. People of all ages have taken to making every aspect of their lives, including their innermost thoughts, public. Nothing is private; intimacy is a lost virtue. How can this be healthy for the individual, or for society?

So the advice of talking less seems to me to be ever more profound and desirable. But there is another part to the declaration: smile more.

I appreciate that the suggestion to talk less is softened by this first part of the sentence. It seems nicer to warn someone about their propensity to chatter too much by saying something nice. But is there more?

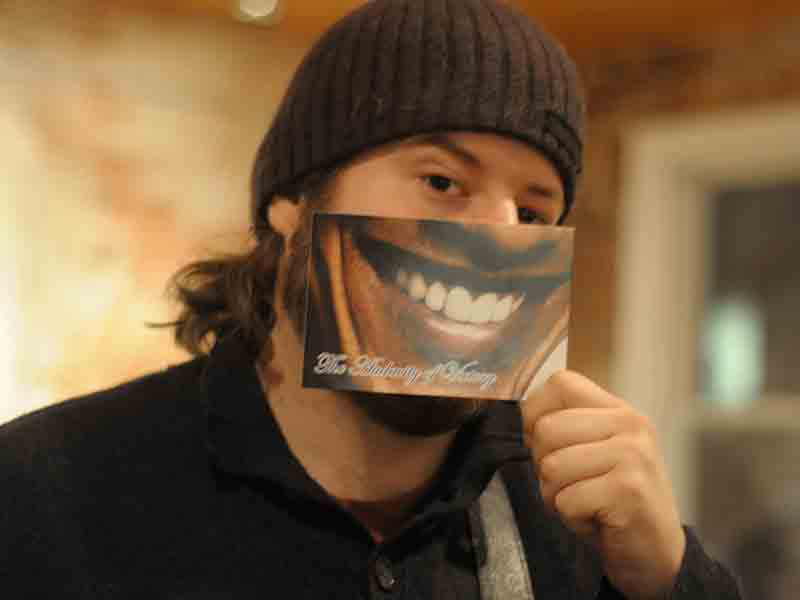

Imagine how easy it would be to walk down any street and be greeted by happy faces. Imagine how much healthier we would all feel if we were surrounded by smiles? People frown too much. Why? Is there too great an effort involved in smiling? Are we afraid that the cheerful countenance appears less important or thoughtful? Does the grin establish foolishness, or can we see that joyfulness as a good omen? Smile at people and see what comes back.

Instead of the corridor of chatter, perhaps the silent smile can become our icon. Quiet optimism and cheerful human emojis, instead of repeated, unrestricted, unimportant and uninteresting self-disclosure, might become a constructive pursuit.

Do I sound like an old stick-in-the-mud, or a reactionary? I don’t mean to. I am not opposed to advances in technology, or social media. It is exhilarating to see what we can accomplish and the speed with which we can communicate. But it is challenging, to say the least, to use these facilities properly and with prudence. I consider that the advice of “smile more, talk less” seems full of wisdom. Taken together, the two halves of the declaration can contribute to our self-knowledge, our patterns of interaction and to our cultural literacy. “Smile more, talk less” is Shakespearean. n