As a student bouncing back and forth between Israel and North America, Amos Oz’s early novels (My Michael, Touch the Water, Touch the Wind and The Hill of Evil Counsel) helped me understand the intricacies of being an Israeli. Born Amos Klausner (like many, he chose a Hebrew family name as part of the Zionist ethos), his love for the language, restored to life with an incredible richness, was another gift, and I knew just enough Hebrew to appreciate it.

Later, Oz’s melancholy semi-autobiographical masterpiece, A Tale of Love and Darkness, wove together the strands (or burdens) of Jewish history and national redemption. His characters were not cardboard cutouts and mythical Sabras from the movies; they were real people with complex relationships and inner lives. He also loved the land of Israel, and his writings portray the green hills of the Galilee, the Judean desert, and the stark contrasts between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, as characters as complex as his human protagonists.

But in international politics, he was never my cup of tea, to put it mildly. Like many gifted artists, I found his views on war and peace to be overly optimistic, or in less polite terms, naive. In his writings and interviews, Oz avoided the central role of power in politics, and instead, focused on individuals and social structures, as he did in his novels. His vision of peace with the Palestinians was based on the assumption that basic human traits are shared by all, and that we all have a primary desire to live in peace and with respect. This is a statement of faith, not political reality.

Echoing his namesake, the biblical prophet Amos, he desperately wanted Israel to be a society based on justice, which is easier in fiction than the Hobbesian world of “all against all.” And like the characters in his novels, his politics were overwhelmed with hesitation and introspection – not a trait that goes well with the hard-nosed political realism required for survival.

At the same time, in his hesitation, Oz respected opposing views, and rejected the language of polarization that has come to dominate social discourse not only in Israel but everywhere. In a public event with Rabbi Jonathan Sacks at Bar Ilan University in 2001, Oz repeatedly stressed the urgency of civility and respect in the Israeli public discourse. His political voice was anchored on persuasion, increasingly insistent, but not to the point of haranguing and debasing those who reached different conclusions.

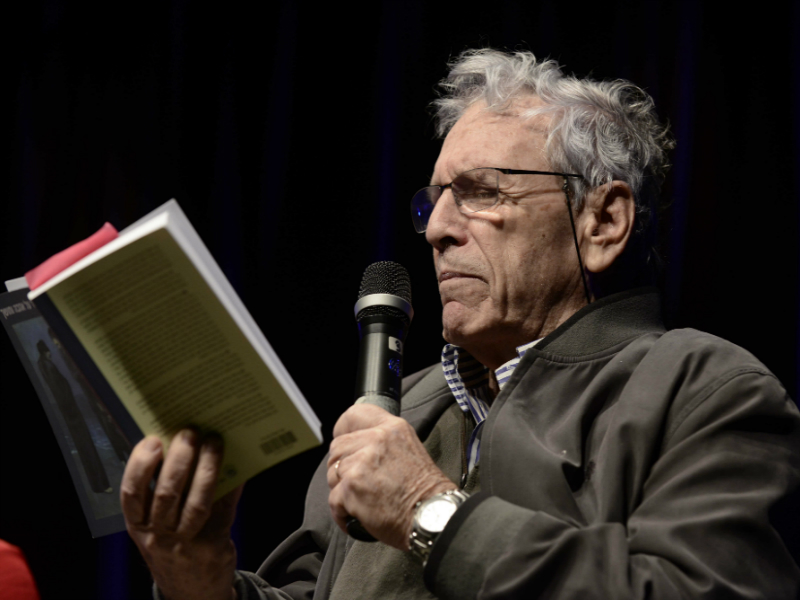

READ: AMOZ OZ, ICONIC ISRAELI NOVELIST AND PEACE ACTIVIST, IS DEAD AT 79

After the Six-Day War in 1967, Oz was an early voice calling for a withdrawal from the newly conquered, or, from the opposite perspective, liberated territories. But as the conflict over boundaries and settlements increased, he remained a hopeful Zionist, and in his many speeches and interviews abroad, he distanced himself from zealots who adopt the anti-Semitic images that portray Israeli soldiers as war criminals and mass murderers.

In 2014, during a war with Hamas, Oz was interviewed in Germany. He pre-empted the attacks by asking: “What would you do if your neighbour across the street sits down on the balcony, puts his little boy on his lap, and starts shooting machine-gun fire into your nursery? What would you do if your neighbour across the street digs a tunnel from his nursery to your nursery in order to blow up your home or in order to kidnap your family?” In these questions, he showed that he was not as naive as he might have sounded.

In his death, Oz reminded Israelis that it is possible to debate the issues of the day with civility and respect, and to hold complex views that cannot be reduced to slogans. And like his characters and narratives, he reflected the complexity and the richness of Jewish history and today’s reality. For the readers in future generations, he has left a very rich legacy.