To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep…

November often coincides with the Hebrew month of Heshvan, during which my family marks the anniversaries of several deaths. This year, the period began on the evening of Nov. 4, with the yahrzeit of my late maternal grandfather, Norman “Norm” Leyton. The act of remembering my zaidy carries on in another way too this month: we honour his memory on Remembrance Day as a veteran of the Second World War.

Zaidy was born Norman Labovitz—he would later anglicize his surname—in Toronto in November 1921, to parents who had immigrated to Canada as teenagers from the town of Linitz, in what is now southwestern Ukraine.

He was raised with Yiddish as his mother tongue on Manning Avenue near College Street, deep in the heart of Jewish Toronto. His was a generation for whom antisemitism was a constant reality. Public parks bore signs proclaiming ‘Gentiles Only’ and the events of the Christie Pits Riot played out mere blocks from his home.

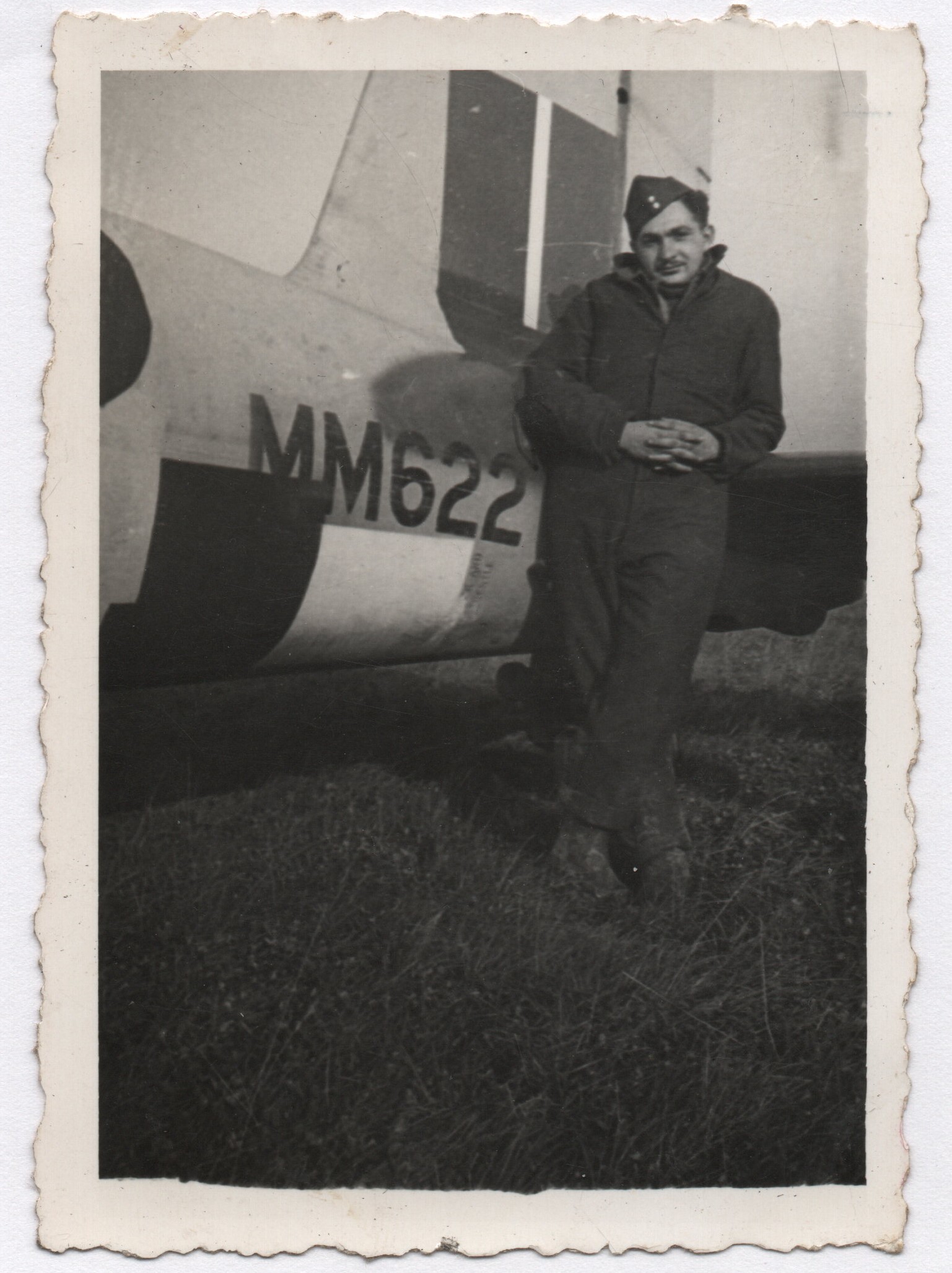

Upon turning 18 in November 1939, he enlisted for service in the war, while he was still in his final year of high school. My family is very fortunate that Zaidy was a prolific amateur photographer. Throughout the war, he carried his camera, documenting everything. We thus see the war unfolding through his eyes—a young 20-something Jew from Toronto, working as a mechanic on the Mosquito combat aircraft in Squadron 409 of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

He was sent to train at the RCAF station in Mont-Jolie, Que. Training was not easy, and antisemitism remained ever present. In his time at Mont-Jolie, fellow trainees made derogatory comments related to his being a Jew. Zaidy punched one square in the face.

In January 1944, he was finally deployed to Europe as a mechanic, spending much of his service overseas in France.

What was it like for him during the war? The stories that he chose to share with the family were mostly light or funny. Rarely did he mention the hardships he encountered beyond an intense dislike he developed for mutton, which he was made to eat far too often.

Yet while his albums show many of the laughs, and their photographs are captioned with witty jokes, they also reveal terrors: death, sickness, and harsh conditions. Indeed, after the war he suffered constant nightmares.

Among the heavy stories that he opened up about, one stands out in emotional starkness to me. On April 19, 1945, his squadron was stationed in Rheine, Germany. His time there coincided with the liberation of many concentration camps in Western Europe and he was sent to aid in the post-liberation efforts as a Yiddish translator. His main task was to inform survivors not to consume too much food, lest they sicken further.

Though he never specified which camp, historical evidence strongly suggests that it was Bergen-Belsen. In my mind, I can consider this encounter, and yet I cannot imagine the trauma.

Though the war ended only some weeks later, he would not arrive back in Toronto until New Years’ Eve 1945. He and my bubbie were married soon after, in February 1946. Zaidy was a proud veteran and proud of his service. He was involved his whole life with the General Wingate Branch of the Legion (the official branch of the Legion in Toronto for Jewish veterans), serving for some years as its president.

It is the among my greatest pains that I never met him. I know him from photographs, papers, and, above all, stories. When my parents named me after him (his Jewish name being Chuna, and mine Chana), they bestowed upon me a great honour: as I carry his name, so too do I carry his memory and legacy.

When I’m not writing about books for The CJN, I am an archivist. If I have learned anything from my profession, it is that you can form a close relationship with someone whom you have met solely through photographs, papers, and stories. They become, in a sense, physical extensions of the person himself.

It’s no wonder that we cry when we come across pictures and letters of parents or grandparents who are long gone. We commune with such documents in highly emotional ways. Such is the case with myself and my zaidy.

Through his writing, I hear his intimate thoughts. In his war documents, I learn about his service. In his photo albums, I see an important moment in history through his eyes. And in his face, I see my own reflected back. I thus pay tribute to him.

Lest We Forget. May his memory be a blessing, yehi zikhro barukh.