This piece will also appear in the Spring 2024 print magazine from The Canadian Jewish News. You can hear Phoebe Maltz Bovy and Avi Finegold talk about what Judaism says about polyamory on The CJN’s culture wars podcast Bonjour Chai.

It’s easy to feel like the world’s last remaining square when reading the many polyamory articles that have appeared recently. They first started cropping up in all those publications with New York in the name (the New Yorker, the New York Times, New York magazine, and the New York Post). Stories multiplied from there—the last one I saw was in the National Post. These days, everyone allegedly has multiple concurrent romantic and sexual relationships, or wishes they did.

What gives?

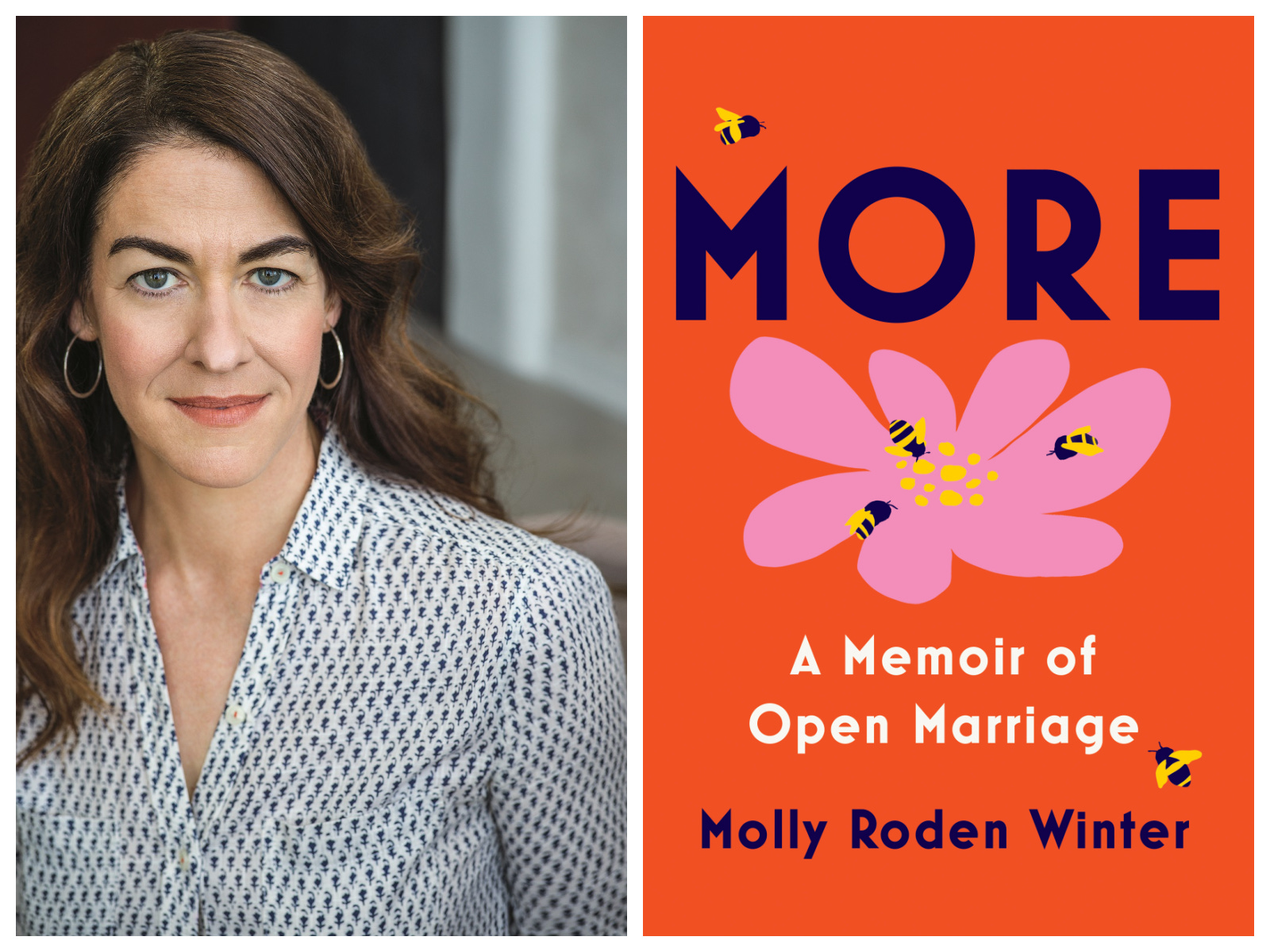

The impetus for this new wave of media interest in non-monogamy is a new book, More: A Memoir of Open Marriage, by the debut American author Molly Roden Winter. Lots of books take on sexy subject matter and don’t get anything like this degree of press. Some credit must go to a publicity team, but the book itself pulls its weight. The clever twist in this new addition to the genre is that Winter, a married mother of two now-young-adult sons, arrives at extramarital adventures as a wide-eyed novice. The reader meets a woman who’d barely been with anyone other than her husband—one who is too embarrassed to buy condoms at her local pharmacy and too shy to visit a local sex toy shop. But she’s an eager pupil. She devours Dossie Easton and Janet Hardy’s 1997 bestseller The Ethical Slut—a GenX sensation that kicked off the last wave of media interest in open relationships—mind-blown to learn that polyamory exists at all. While sometimes this aw-shucks stance reads as disingenuous (she also mentions having gone to a sex club with her now-husband years prior), the easily scandalized narrator allows the book to read like a journey.

If you’re picturing an erotic romp, you will be disappointed. More reads as a cautionary tale about what can happen—doesn’t always, but can—when a woman is financially dependent on her husband. In tenor if not artistry of writing, it’s of a piece with poet Maggie Smith’s bestselling 2023 divorce memoir, You Could Make This Place Beautiful. While the couple at the centre of More stays together, it’s very much the same how-do-these-things-still-happen story of a smart, well-educated woman who marries a high-earning man, has a couple of kids, and tells herself she has accepted her role as the submissive-in-the-unsexy-sense one in the marriage—only to have the same realization as countless women before her about the drawbacks, autonomy-wise, of such an arrangement.

***

There is a whole literature on Jews and polyamory: in the Bible, in history, and in modern-day secular and religious settings. Does More belong on that shelf? Elsewhere, Winter has mentioned converting to Judaism, but there’s no discussion of this in the book itself. Winter keeps things simple, spirituality-wise, and sticks with her conversion to polyamory, and to a side plot about her mother’s own arguably more compelling finding-herself journey into a Japanese cult. Jewishness only comes up when she mentions that Mitchell’s last name suggests he’s Jewish (this is never confirmed, nor brought up again), and in what I think is meant to serve as the meet-cute story of how she got together with her now-husband.

Is it cute? Judge for yourself.

Winter writes that when she first met Stewart, she assessed that he wasn’t her “type,” because “he fit every negative stereotype of a Long Island Jew.” This, for her, apparently means having a problematic sense of humour and wearing pleated pants. (I may be a Manhattan Jew by birth but I am guilty on both counts.) It’s meant to be romantic, I guess, that she looked past what she interpreted as his distinctly Jewish brand of unpleasantness. All this anecdote accomplished was to make me think that these people—she with her casual anti-Jewish quip, he with his unwillingness to lift a bottle of dish detergent—might just deserve each other.

The subsequent story of how Winter’s marriage opened up is neither titillating nor empowering. Stewart has come home late from work, again, leaving her with all the childcare and housework, as usual. She storms out of the house in a huff and ends up going out for drinks with a female friend. At the bar, she flirts with a man, imagining that she is somehow getting revenge on her husband. And then she comes home and learns that not only has she failed to get a rise out of Stewart, but that he’s into it: he finds the idea of her with other men a turn-on. They renegotiate the terms of their marriage such that both are allowed to have outside sexual partners, and, eventually, additional long-term romantic relationships.

All of this might sound modern, but the home life she describes with her husband, who remains her primary partner, strikes me—and her!—as bleak and archaic. They have two young sons, but he comes home after they’ve gone to bed and works on weekends, even once she’s returned to paid employment herself. She thinks “about all the years I’ve spent my nights alone with the kids—the dinners, the bedtimes, the dishes, the loneliness of doing it all by myself.” She writes that she “love[s] being a mother,” but why must she do everything? She wonders this. I wonder this.

The why is addressed, in a sense. Winter and her husband eventually uncover, in couples’ therapy, that the reason she had done all the childcare when the kids were little — which he doesn’t dispute — is that she was a control freak and he had worried he’d get it wrong. This is presented as a therapeutically brilliant revelation about her perfectionist tendencies, rather than the sort of psychobabble a man might come up with to retroactively explain why he had saddled his wife with all domestic responsibilities. You’d think Betty Friedan never existed, let alone the many waves of feminism since. The heterosexual landscape she inhabits seems at least 50 years out of date. Somehow, despite the More’s many orifices and contortions, the result is less Carrie Bradshaw of Sex and the City than Edith Bunker from All in the Family.

***

Prowling for strange men offers Winter not so much liberation as a distraction from life as a doormat—or maybe just an opportunity to serve as a doormat for a wider pool of men. She meets some real charmers, like one man with questionable integrity regarding condom usage, and another who turns out to be playing the long game to get her into bed with his girlfriend. (Winter is not bisexual but acquiesces.) These liaisons generally take place after she has done her kids’ dinner, bedtime, and clean-up. She waits for her husband to get home from work or ‘work’ or wherever he is, so she can head out. This is time she should be sleeping. (“‘I did not sleep very much,’” Winter confirmed to the New York Times in an interview.) She writes about working with her therapist to sort out why she keeps getting migraines, anticipating some existential revelation, when—if I may armchair diagnose—it seems more likely to be a sleep deficit. My head hurts just thinking about it.

That polyamory might not always be the most woman-friendly arrangement becomes obvious if you think about why plural marriage came to be stigmatized, even outlawed, on liberal grounds. (The Wikipedia entry for Polygamy has a clarification note up top: “Not to be confused with Polyamory or Polysexuality.” I am going to ignore these instructions and will make the case that one should, in fact, confuse these two things.)

Polyamory may distinguish itself by “the informed consent of all partners involved,” but the world does not operate according to definitions. The deeply rooted cultural practice of a certain sort of man amassing a group of women for himself, cannot not reappear under the guise of consensual non-monogamy.

Do not take my word for it. Advice columnist and podcaster Dan Savage has long suggested that straight people adopt the easy-breezy attitude towards “ethical non-monogamy” favoured by many gay men (for whom these gender dynamics are not, for obvious reasons, an issue). With polyamory the topic of the moment, he recently took a call from a despondent woman in an open relationship. Her boyfriend of a year had moved on to another woman while still stringing her along. What’s his incentive to make a clean break, though, if they’re polyamorous? The call put Savage in an awkward spot, which he acknowledged.

“There’s a lot of… atheistic Mormonism being shipped under polyamory these days,” he said on the podcast, referring to the caller’s boyfriend’s behaviour as “typical, biblical straight male assholery.”

In other words, people may claim they’re doing a very modern and feminist version of open marriage, while the on-the-ground realities suggest nothing of the kind. Consider that an early manifestation of modern open marriage was called wife-swapping. Yes, technically the swinging went both ways, but it’s right there in the language who’s actually calling the shots. Consider, too, a New York magazine mention of a polyamorous rule pattern wherein outside partners are allowed, but only if they have female genitalia. Not unlike monogamy, polyamory as it exists in the world—as separate from the Platonic form of polyamory described in books on the subject—often winds up being more favourable to men.

In this post-#MeToo age of thinking critically about consent, does it not stand to reason that a woman who is financially dependent on her husband might ‘consent’ to an open marriage, not because she’s a free spirit, but because her choices are constrained? While More is not a straightforward case of a wife looking the other way at her breadwinning husband’s dalliances, it’s not far off. That Winter, too, has lovers changes little. Her doing so is not an assertion of power within her marriage, or even something she gives much indication of enjoying. I base this not only on the surprisingly scant (but not altogether absent) erotic moments, but also on how often Winter writes about not wanting an open marriage. There’s the time she tells a couple’s therapist, “We’re here because I don’t want to be in an open marriage anymore. But Stewart does.” Then there’s that time she vows to “tell Stewart that I tried as hard as I could, but I just can’t do open marriage anymore.”

Winter cavorting outside her marriage caters to her husband’s proclivities. He likes picturing her with other men, and understands that as long as she’s doing so (even if it is somewhat at his behest), he gets to date other women. Win-win as far as he’s concerned.

While her lovers disappoint, there is one steady Other Man in Winter’s life: Mitchell, her therapist. He does what Stewart will not or cannot: puts her needs first. Mitchell gently raises the question of whether she’s using extramarital sex as “an illusion of freedom.” She gestures at contemplating this, regarding her own life and her mother’s, but doesn’t appear to quite listen to this point. As Tyler Austin Harper writes in his Atlantic review of More, “The only solution [Winter] can imagine is to persist in an open marriage, rather than push for an equal one. Inward sexual revolution plainly feels more possible than a revolution in who does the dishes.”

Much of the criticism of More has centred on the couple’s socioeconomic privilege, and the way it’s easier for upscale married people to mess around without consequences in an era when the less well-to-do struggle to get married in the first place. “Polyamory, the Ruling Class’s Latest Fad,” reads Harper’s Atlantic headline. The New Yorker casts its own wary eye at “the new monogamy skepticism of the moneyed,” and takes a not-unjustified dig at Winter for noticing that a lover’s apartment lacks a mudroom.

Money barely comes up in the writing—perhaps, unlike the author’s urinary tract infections, it is too personal—but there are clues. Indeed, the biggest tell of them all is that money itself barely comes up. A new lover starts massaging her feet, prompting her to write, “I’m thankful I squeezed in a pedicure yesterday.” Affairs and nail salon visits, in this economy? Blithe spending abounds. The real estate angle, however, makes the rest look like peanuts: Winter and her husband buy and renovate a house in Park Slope, a housing type that today costs several million U.S. dollars.

So yes, these are rich people, living in the rarefied worlds generally covered by lifestyle articles. But at least as relevant to More is where she fits, financially, within the relationship. It’s clear in the book—as much as it can be without their tax documents—that she’s the lower-earning (and, while a stay-at-home mom, non-earning) spouse. She refers to Stewart as the family’s “provider.” While the balance of power may change now that she’s a famous author, More is about a woman with little leverage in her relationship. At various points, he wants an open marriage and she does not; it’s making her unhappy. Each time, this resolves itself with her having some epiphany about how she wants the same thing he does so actually everything is fine. Is it, though?

For more original Jewish culture commentary from Phoebe Maltz Bovy subscribe to the free Bonjour Chai newsletter on Substack.

The CJN’s senior editor Phoebe Maltz Bovy can be reached at [email protected], not to mention @phoebebovy on Bluesky, and @bovymaltz on X. She is also on The CJN’s weekly podcast Bonjour Chai.