In 1923, Rabbi Meir Shapiro (1887-1933) of Poland proposed a novel course of study that he hoped would unify the Jewish world: the daf yomi, literally “the daily folio.” Since the Babylonian Talmud consists of 2,711 folios (a folio is two pages), he proposed that people study a folio a day and thus complete the study of the Talmud in around 7 1/2 years. At Rabbi Shapiro’s suggestion, a schedule of folios was created so that students of the Talmud could be (almost) literally on the same page as each other every day. As he put it, “[A] Jew leaves the United States and travels to Brazil or Japan, and he first goes to the beis medrash [the house of study], where he finds everyone learning the same daf that he himself learned that day. Could there be greater unity of hearts than this?”

Daf yomi was not an instant success. Investing time every day in an activity that takes so many years to complete requires sincere dedication and discipline. The Talmud also is not an easy text to study. Many serious students of Talmud scoff at the daf yomi project, claiming that it trivializes Talmud study, since you really need dozens of hours to do justice to a talmudic daf.

But partially because of the growth of the Internet and the ready availability of daf yomi podcasts and other study tools, more and more Jews have taken part in the last three cycles. (I also think it fits in with current competitive fads like marathons, triathalons, etc.) Daf yomi students are predominantly haredi men. But this pattern, too has changed in the last cycle or two.

READ: WARTIME MEMOIR SHARES A YOUNG MOTHER’S COURAGE

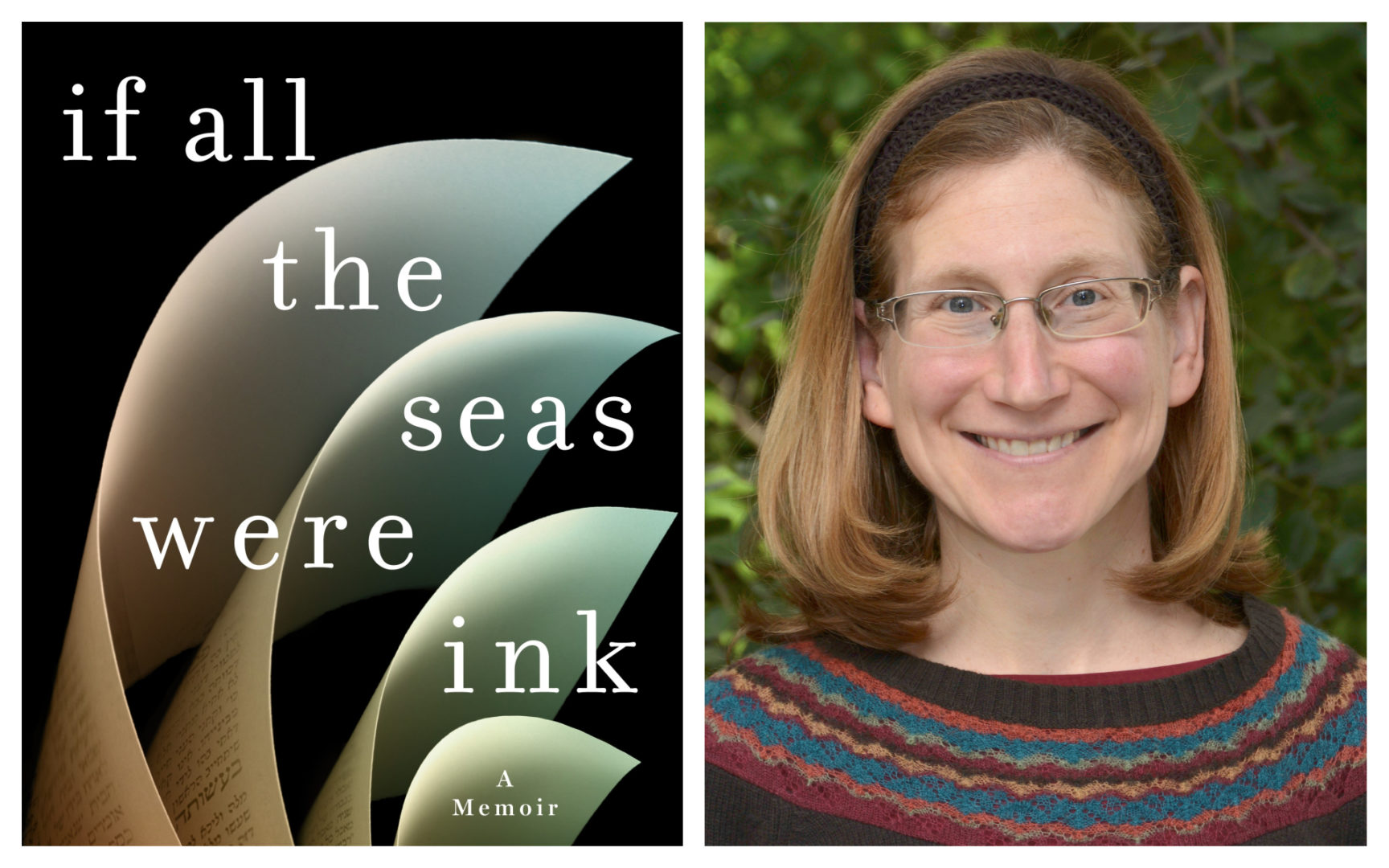

Ilana Kurshan, a brilliant young graduate of Harvard and Cambridge, recently completed the daf yomi cycle and wrote about it in If All the Seas Were Ink: A Memoir. She began her study of the daf as a recently divorced 27-year-old American woman who was feeling down. She was living in Jerusalem, mostly because her former husband had wanted them to move there, and she was trying to decide whether to stay, and what to do with her life. By the time she completed the cycle, she was still in Jerusalem, but by then she was happily married and the mother of three.

Kurshan walks us through each of the volumes of the Talmud. She highlighted texts that were meaningful to her. She is a Talmud enthusiast: “Nothing is as exciting as the next page of Talmud.” She interweaves explanations of Talmud with autobiographical information, telling her story of finding love and happiness in Jerusalem.

Her approach to Talmud is personal and creative. For example, the talmudic volume, Sukkah, teaches that fixed meals have to be eaten in a sukkah but snacking, what the Talmud calls achilat aray, temporary eating, can take place anywhere. (Kurshan playfully calls it “achilat awry.”) At the time when she was studying Sukkah, she was recently divorced and felt that much of her life and even her eating patterns were aray. Furthermore, by definition, a sukkah is a temporary structure but it has to have a certain amount of stability. Kurshan compares this to her own personal status while she studied this volume, living a life that seems flimsy and temporary while trying to find permanence and stability.

Kurshan’s academic background is in English literature and she makes her living as a translator and editor. Her writing style is engaging, sometimes even lyrical. She makes surprising but compelling connections between talmudic ideas and some of the finest works of English literature. She wrote playful poems to help her remember what she studied. For example, to remember a story told in Ketubbot 121a, she wrote: “A beautiful maiden-girl said/To the suitors who flocked “But I’m wed!”/And once every last dope/Had abandoned all hope/She married her heart’s choice instead.”

READ: MEMOIR TACKLES OBSESSION, EATING DISORDERS, SEXUALITY

Surprisingly, the book could have used better editing and fact checking. In a famous talmudic disagreement (Sotah 20a), one rabbi says that a man is required to teach Torah to his daughter, but one of his colleagues strongly disagrees. Kurshan explains this dispute twice in the book and quotes the opinion of the naysaying rabbi in two different translations: “Anyone who teaches his daughter Torah teaches her frivolity” and “If a man teaches his daughter Torah, it is as if he has taught her promiscuity.” (“Promiscuity” is the more accurate translation.) The assertion that “Moses Maimonides famously stated that ‘From Moses to Moses, there was no one like Moses’” is inaccurate. It was Maimonides’ admirers who said this about him, after his death.

Kurshan’s insights into marriage can be uplifting: “The challenge of constantly bearing in mind the dignity and integrity of a fellow human being is, in a sense, the essence of marriage.

“The mere fact that we [she and her husband] have merited to spend our life together seems proof of divine providence.” Refreshingly, she also refers to her first husband many times in the book without saying anything critical about him.

The Talmud is hardly a feminist work and Kurshan is a modern feminist. Nevertheless, her respect for Jewish tradition helps her rise above the temptation of mocking or belittling this Jewish classic. An important lesson to learn from this inspiring book is that the Talmud belongs to all Jews who dedicate themselves to its study, women and men, conservative and liberal.