Bruce Kidd offers an excerpt from his new memoir, A Runner’s Journey, beneath this introduction for The CJN:

Sports are a journey of discovery. I’ve rarely run a race, played or watched a game without learning something new.

Through sports, I have learned and relearned about desire, strength and vulnerability. In addition to the great joy that they bring, sports have taught me about other people, their places and cultures. They have encouraged me to dream and see the world. I’ve spent a lifetime of learning through sports.

In my teenage years, enabled by family and community, I became a successful distance runner, learning to win and set records across Canada, the U.S., the U.K. and Australia, expanding my horizons in the process. It was a time when conventional wisdom had it that teenagers could not run longer distances without damaging their health. I paved the way for others like me by showing that when properly trained, we could compete in endurance events as well as anyone.

Along with Bill Crothers, Abby Hoffman and Harry Jerome, I helped jumpstart a rejuvenation of Canadian fortunes in international sport. We sought to challenge the world and we did.

We also sought to change Canadian sport so that the next generation could have better opportunities.

My parents always encouraged me to take responsibility for the activities in which I engaged, so using my celebrity (and the protection of white, straight, male middle-class privilege) to make change seemed the logical next step. It was the start of lifelong advocacy for greater public investment, more competent leadership and genuine accessibility, in both high performance and grassroots sports.

It was not just access to sport that I began to see critically, but the way sports were organized.

Alongside the undeniable benefits, I realized that sports empower some while disempowering others. Sports have enabled terrible abuses. I gradually became an ally of the maltreated.

This memoir is about why sports means so much to me, what I learned from them and why I’ve always fought to make them more equitable and humane. It bears witness to the remarkable changes I have lived through in more than 70 years of participation.

The Beach had a well-deserved reputation for sports. It was fiercely British, with professional, skilled working-class and small business families living side-by-side, unabashedly Christian and white in origin and background. Two world wars had only strengthened its attachment to Britain.

When King George VI died in 1952, my stern Grade 3 teacher Miss Fitzgerald at Balmy Beach School cried and cried. While other parts of the city had been experiencing non-British immigration since the 19th century, and had begun the innovative accommodations that prefigured the “multiculturalism” that characterizes Toronto today, none of that was happening in the Beach. There was only one Black and one Jewish family in my high school, Malvern Collegiate. My mother caused a stir in St. Aidan’s Anglican Church when she took a Bengali graduate student who was boarding with us to services. In the 1961 census, 91 percent of males were either Canadian- or British-born.

Like Britain, the Beach was revered as the “home of sports.” Sports were by far and away the most followed and supported form of public culture. There were cherished facilities (Balmy Beach Canoe Club, Kew Gardens, Pantry Park, Woodbine Racetrack, Grand Trunk Field, and after 1954, Ted Reeve Arena), and famous teams like Tip Top Tailors, which won the 1949 world fastball championship, and the Balmy Beach football team that (until 1954) regularly challenged for the Grey Cup. For boys, there were strong school, playground, church and other community programs.

It seemed that famous athletes lived on every street. I was a delivery boy for many years, first groceries, then pharmacies, then the Globe and Mail. I loved those jobs. They gave me confidence, spending money and experience in interacting with people of different backgrounds.

I could always boast about the current and past stars who came to the door. At one time or another, Olympic paddler Roy Nurse, Argonaut greats Peter Bennett, Ab Box and Alex Ponton; Maple Leaf hockey captain Sid Smith, and Maple Leaf baseball star Bobby Porter were customers. None of them talked about their exploits but we knew.

While the Beach also produced Glen Gould and Teresa Stratas, they were outliers, as the accomplished literary critic Robert Fulford often noted. He couldn’t wait to get out of there.

I learned the basic skills and rules from my parents, their friends and neighbors. My father, two uncles, an aunt and many of their friends had been leaders in the YMCA, and they all encouraged my interest in sports. So did my mother, who played sports in school and university, and was an avid swimmer and skier. One of my father’s classmates at Sir George Williams University, Howard Langille, opened a ski hill near Dagmar, Ontario, and before we got a car, we would take the “ski train” up there on weekends.

Other friends of my parents, John and Betty Madsen, had turned a barn in Unionville into a well-equipped gymnasium and taught educational gymnastics in the Danish folk school tradition. We would go by train to spend afternoons climbing and jumping.

I learned to swim at the Broadview Y and at Geneva Park, the Y’s conference centre on Lake Couchiching where we would take a cottage every summer. We learned and played all manner of field games at Y day camps in the Don and Highland Creek valleys, and canoeing and camping at United Church and Y stayover camps in Muskoka (Tobowobo, Pine Crest), Haliburton (Wangoma), and Howe Sound (Elphinstone) in British Columbia, where my father had been a counsellor. I learned an appreciation of leadership and what I would call “optimist sporting values” from the Y.

While we were mostly on our own in organizing games in the neighborhood, adult influence was never far away. If your parents weren’t around, other adults would step in to stop a fight. My parents and their friends followed baseball, hockey and football and talked about them all the time. If there was a game on the radio or TV during my deliveries or collections, people would invite me in to listen to, watch and discuss a few plays. Although my father had left Saskatchewan, the province of his birth, at the age of four, he always cheered for Saskatchewan and other western Canadian teams. We listened to Foster Hewitt (hockey) on the CBC, Wes McNight (football) on CFRB, Joe Crysdale (baseball) on CKEY (baseball) and Rex Stimers (St. Catharines Teepees hockey) on CKTB. Until we got a TV, I cultivated friends with sets to watch sports. I read the sports pages avidly, and as soon as I earned enough from my part-time jobs to pay for subscriptions, signed up for The Hockey News and Sport.

I watched as many games in person as I could. My parents introduced me to Kew Gardens, where Tip Tops’ star Charlie Justice pitched, Varsity Stadium (Blues and Argos), Maple Leaf Gardens (Leafs, Marlies and St. Mike’s) and Maple Leaf Stadium, where the professional baseball team played.

Before long, my friends and I went to games on our own, walking, cycling or taking the streetcar, taking advantage of children’s prices. At Maple Leaf Stadium, you could sit in the right field bleachers for 15 cents. For Sunday doubleheaders with the Marlies and St. Mike’s at MLG, if you could find an adult to buy one ticket in the reds, the best seats, you could get kids’ tickets next to theirs for 50 cents. Sometimes, except for the one adult, often a complete stranger, we had the whole row.

While my parents talked about other parts of Canada and the world, and before I entered high school, twice took me across Canada to visit my grandmother on the west coast (once by train; once by car), sports taught me the most about geography, beginning with the routes and neighborhoods I discovered on the way to games and practices. I quickly developed my own lived map of the city. My parents encouraged those explorations. My mother refused to give us streetcar tickets for any distance that my youngest sister Dorothy, born in 1953, could walk. We were convinced that she trained Dorothy to cover longer and longer distances!

The Queen car was our gateway to the world outside the Beach. Neville was the end of the line, so you could always get a seat going into the city. You were never afraid of falling asleep on the way back because the conductor would wake you to let you out. I loved those streetcars, and always had a favourite seat on every model, starting with the coal-heated Peter Witts I began with.

Although children’s sports have a long history, the phenomenon of “mother’s taxi”–parents organizing their lives around children’s practices and games–was only in its infancy. My parents rarely saw me play and that was the norm. If anything, it was still a time when the children watched their parents and other adults play top-level sports, mostly men but even some women (in fastball).

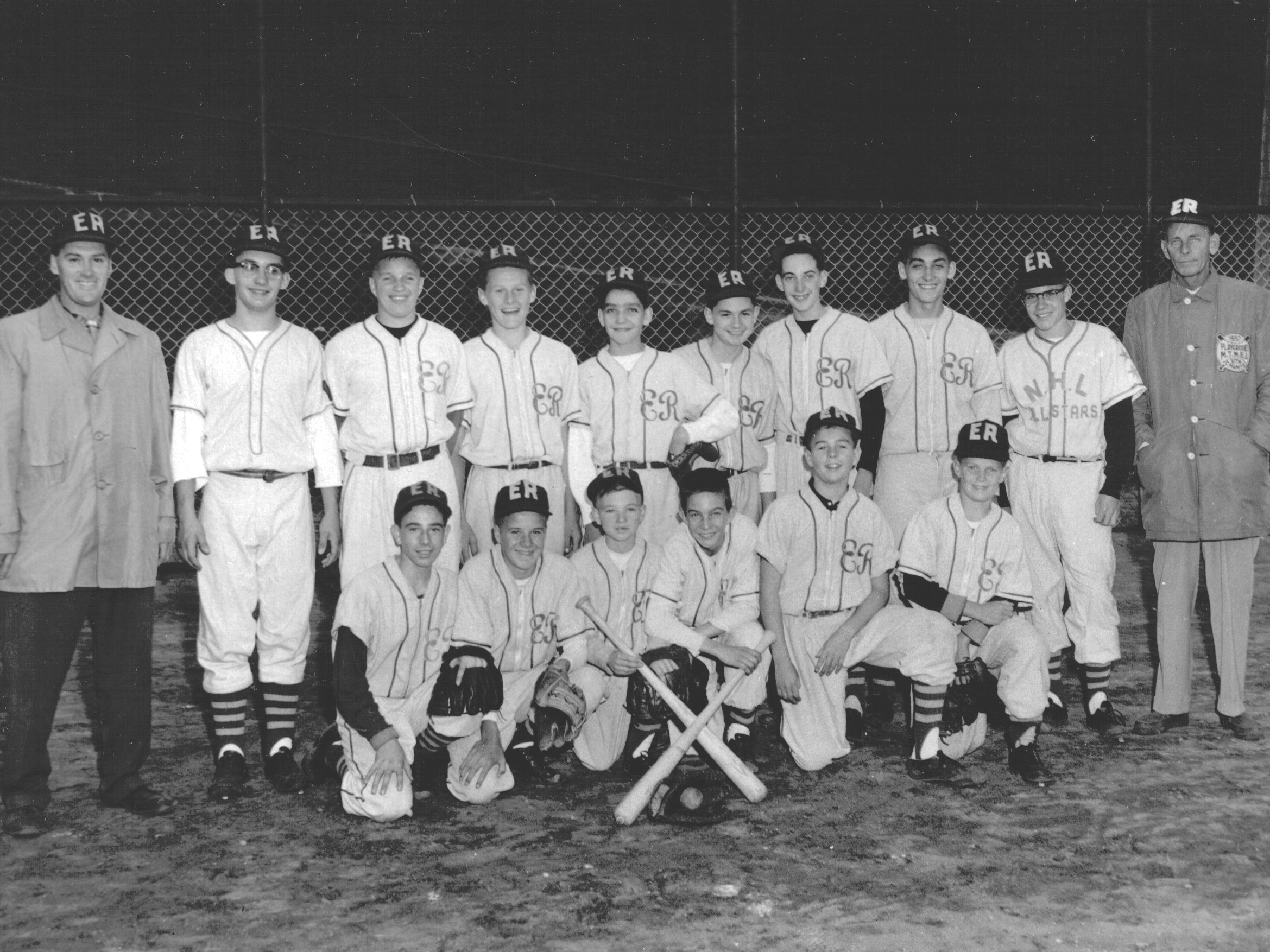

While I competed in every sport, including hockey, rugby, football, basketball, volleyball, and track and field, softball/baseball was my favourite. That’s where I first experienced success. As I got older, I played for as many teams as the rules and the schedules allowed. In a single season, I could play softball for the school, a local church and a team in one of the community leagues, and hardball for a playground team. Usually I played in the infield, sometimes I caught, and on a few occasions, even pitched. In 1955, my peewee softball team from Kew Gardens, sponsored by Wineva Pharmacy, won the city championship. The following year, East Riverdale, the playground team I played for out of Greenwood Park, won the CNE’s very first peewee baseball tournament as well as the city championship. The Toronto Star’s Jim Proudfoot wrote that I “shook up North Toronto’s composure by scooting all the way home after the catcher dropped a third strike.” In 1957, I pitched my Blantyre Park softball team to the Scarborough championship, and East Riverdale won the city baseball championship. I threw myself into games and became extremely distraught when we lost. We got crested jackets and I wore them until they fell apart.

It was all very heady. The only photos I have of myself in those years are from playing baseball.

My parents preached fair play and other ideals of sport. They abhorred fighting in hockey, and my father condemned Leafs’ owner Conn Smythe for his attitude of “If you can’t beat ’em in the alley, you can’t beat ’em on the ice.”

For the most part, we were lucky to have competent, responsible adults as coaches and mentors.

When sports conflicted with violin, Mr. Daly at Balmy Beach always found a way to enable me to do both, even if it meant hiring a taxi to get me from a game to a music practice. John Flynn at East Riverdale was a stickler for the fundamentals and “doing it right.” He had no use for players who “just wanted to have fun.” How can you have fun, he used to say, if you’re not doing it right?’ John prepared me very well for the focus on training and discipline that in a very few years would dominate my life. Vince Downs was another East Riverdale coach who gave me lifelong lessons about sporting values. He had played Triple A, was a terrific instructor, and a devoted Catholic. We deeply respected him.

There was a taken-for-granted level of trash talk, antisemitism, racism and ethnic slurs in east end sports, and (although it would have horrified my parents) I used to rag batters on other teams endlessly. I found I could get under their skins and make them tense up, especially if I was playing up close at third or behind the plate. I could see that it upset Vince but I rarely stopped.

Then one day, when we were playing our crosstown rival Lizzies at Christie Pits, I repeatedly heckled a rather rotund boy about his weight. He just froze, swinging at one bad pitch after another. Vince stopped the game, called me aside and said something like: “Those are Jewish boys whose mothers pressure them to eat for reasons that are too difficult to explain. If I ever hear you ever razz them again, you will never play for this team again.” From Vince, I learned to keep personal and cultural attacks out of sports.