- “In 1738, a young transgender man named Jacques LaFargue set off from France to what is now Quebec City, determined to make for himself a new life.”

- “At the beginning of Jewish history in Canada, there was a woman. In 1738, Jacques LaFarge, a recently arrived sailor in Quebec City, was arrested for suspicious behavior.”

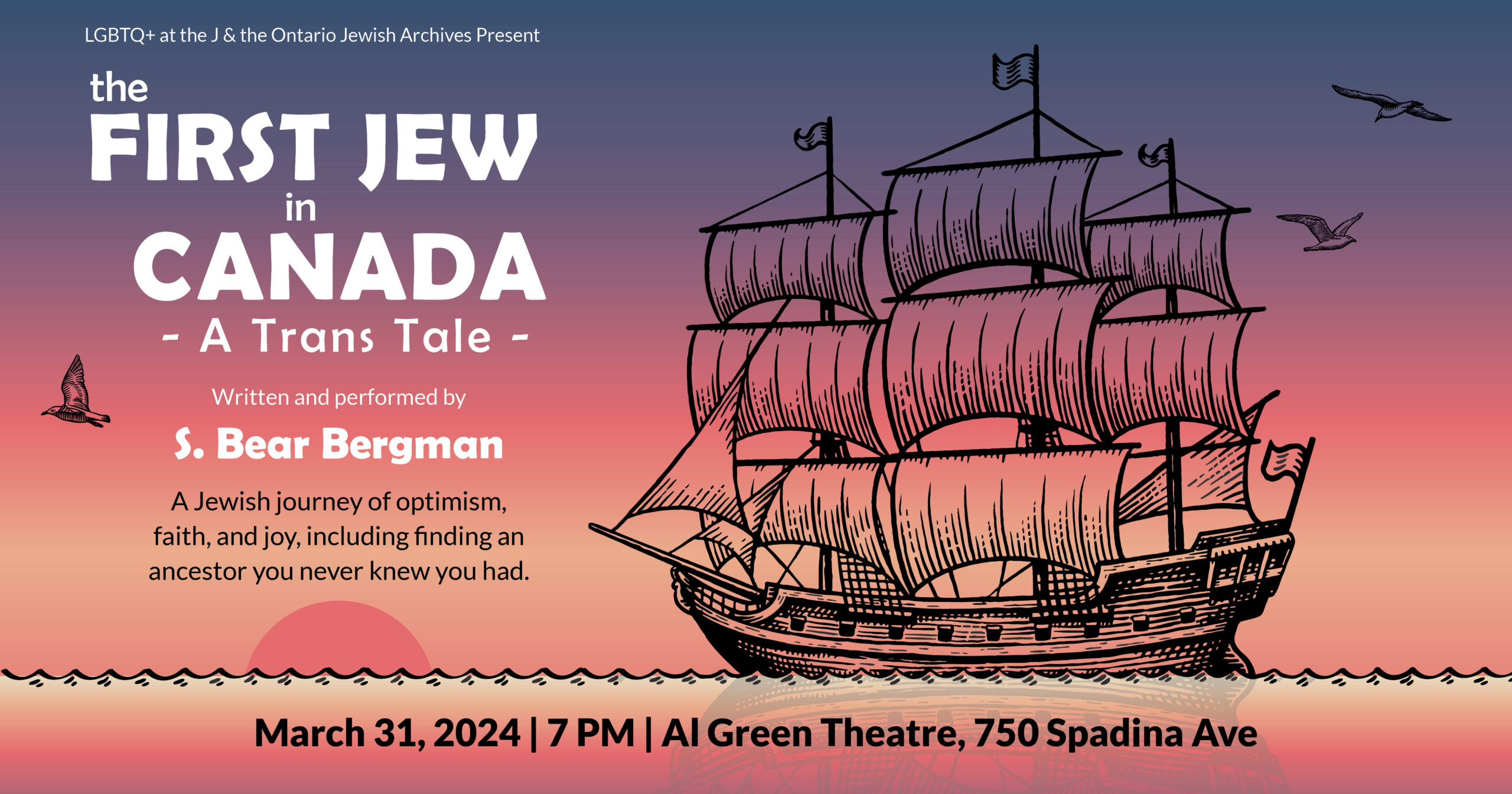

So explain, respectively, the official description of First Jew in Canada: A Trans Tale, a live theatrical performance slated for March 31 at the Miles Nadal JCC in Toronto—and the wording from a Jewish Women’s Archive entry about Canadians.

These two write-ups are referring to the same individual. An individual whose last name has no consistent spelling—but that’s the least of it. If you want to learn more about this person, you might want to do a search for “Esther Brandeau.”

I will admit that when I saw a play described as being about a “transgender” individual living in the year 1738, I was less than persuaded. S. Bear Bergman’s play itself sounds neat, but… there weren’t trans people in 1738! There weren’t cisgender people, either. Not gays, straights, or bisexuals. Virtually all the ways we describe gender and sexual identity today weren’t around as concepts more than about five minutes ago. The idea that your spouse ought to be a person with whom you were romantically in love, also a relatively new invention.

That said, it is easy enough, some of the time at least, to point to historical figures and say, OK, this person consistently had same-sex relationships and would have been gay if living in our times. It’s not far-fetched to assume someone history books describe as a man who cross-dressed all the time and used a woman’s name and female pronouns would have been, in today’s society, a transgender woman.

Where it gets complicated is the story of people assigned female at birth who went on to live publicly as men, in times and places where this was the only way they could make something of their lives.

Stories of this nature come up periodically, and the stakes are basically this: On the one hand, trans people exist, and always did (even if terms didn’t always convey this), and trans people—like other members of marginalized groups—seek out their own histories.

On the other, the whole entire point of feminism is that women often find female gender roles confining, on account of the whole wanting to live as a full human being thing. And this is different from the more general thing where gender roles are restrictive for everyone, even men. All the more so if you go back centuries. Women who wanted to do such things as be publicly romantically involved with other women, or not wear a corset or whatever, or enter Canada in 1738—something this very same person also had to pose as Christian rather than Jewish to do!—might use he/him, simply because there was no way to do such things as a she/her. Ever heard of Joan of Arc? Or the Isaac Bashevis Singer-cum-Barbra Stresiand story of Yentl the Yeshiva Boy? Everyone knows this was a thing, it was even a 1986 Blackadder episode.

So when you get a historical figure like “Esther Brandeau | Jacques La Fargue” (Heather Hermant’s coinage), there’s no straightforward answer to who they were. You cannot assume that the donning of a male persona meant, 100 percent of the time, that this individual was a he/him whom one would be deadnaming if using Esther Brandeau. To do so is to effectively abandon feminism, and to claim that women throughout history were not oppressed but rather affirmatively content with their lit.

You also can’t know otherwise. Because yes, even back in the day, there doubtless were some people of whom the midwife said ‘It’s a Girl!’ who didn’t see themselves as such. Along not entirely dissimilar lines (though there are, obviously, differences), that Jews were forced to convert to Christianity at various points in history doesn’t mean that there weren’t sincere converts from Judaism, who really believed Jesus and all that. People are complicated!

My hunch where such figures is concerned is that if they were living today, most probably would identify as women, a disproportionate number (but not all) as queer women, and some as transgender men or non-binary. I think artists should be free—and demonstrably are free—to interpret historical stories like these as feminist or trans-affirming or whatever they see fit. I also think audiences—and community members more generally—are free to come to their own conclusions.

I hate hate hate the social-conservative thing of trying to cancel trans content, and am glad to see that this play is being produced. I’m also not the greatest fan of having to nod along to the idea that someone who had been recognized as a groundbreaking Canadian Jewish woman isn’t part of our history and actually if you try to claim her as such, you’re on the wrong side of history.

The following line, from the posting about the play, jumped out at me: “If you identify as somebody who is trans, nonbinary, and/or gender expansive and cannot afford the full ticket price, you can select a reduced ticket price to increase access.”

Are all women who have jobs or wear pants or refuse to submit to their husbands (or to have husbands at all) included under “gender expansive”? If yes, then there’s nothing to see here.

For more original Jewish culture commentary from Phoebe Maltz Bovy subscribe to the free Bonjour Chai newsletter on Substack.

The CJN’s senior editor Phoebe Maltz Bovy can be reached at [email protected], not to mention @phoebebovy on Bluesky, and @bovymaltz on X. She is also on The CJN’s weekly podcast Bonjour Chai.