Stanley Diamond started compiling his family tree 40 years ago, after he learned that his nephew had a rare genetic disease. Suddenly, it became imperative to find as many of his relatives as he could and warn them, he recalled.

For Judy Kasman, a child of Holocaust survivors, the search for her family history, which she thought was lost in the war, began with finding just one record on a genealogy website.

And Neil Richler was still a teenager when he stumbled across some early genealogy software and started entering what he knew about his family history, consulting his grandparents and one great-grandparent who were still alive.

No matter what the trigger was, for amateur Jewish genealogists, a pastime can quickly become what Kasman calls an “obsession.”

“You never finish, it’s not like you put in a final piece of a puzzle. There’s always new databases coming up,” she said.

At 45, Richler is still one of the younger members at genealogy meetings, even though the hobby has become more popular. It is the thrill of the search for a previously unknown relative that keeps him going.

“It’s a mystery where your family is in the starring role,” he said. “When you put it all together, it tells your story.”

Tracing a family’s roots across generations – and continents – has always been a hobby for amateur genealogists, but as dusty records became searchable online and with the advent of cheap, widespread DNA testing, it has become even easier to build your family tree, yet at the same time more overwhelming.

Internet databases bring up millions of records with just a few clicks. Meanwhile, DNA testing, especially in tight-knit Jewish communities, reveals lengthy lists of strangers who are somewhere on your family tree. For many, the challenge is knowing where to dive in.

The first step that genealogists suggest may seem obvious: talk to the oldest members of your family and gather the stories and relationships they wish to pass down.

Richler also suggests finding the oldest people who have known your family, who will have a different perspective and may know stories that have been forgotten or left untold by your family.

Richler also had the DNA of the oldest members of his family tested, providing information that may prove useful sometime in the future, he said.

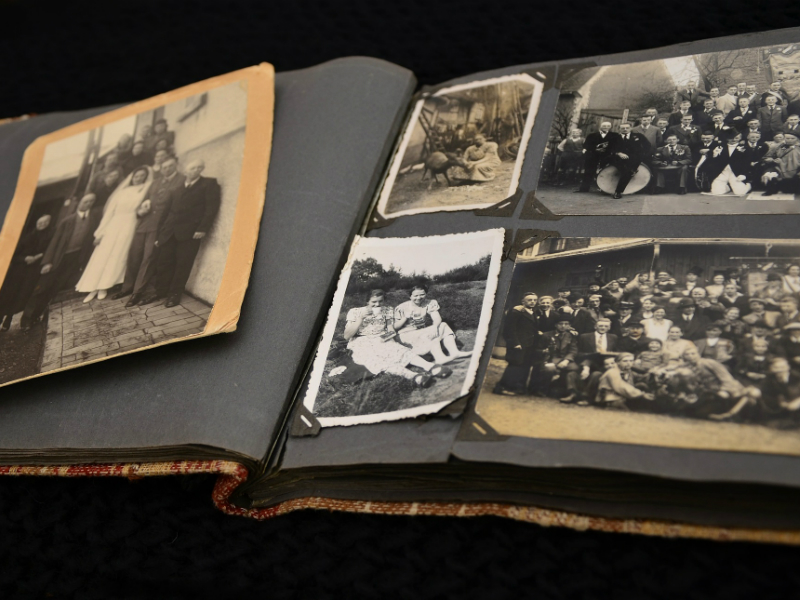

Often the urge to trace family records starts after a parent dies, Diamond said, sometimes when a child finds a shoe box filled with photos and records that person had never seen before.

From there, the next step is to visit the local Jewish genealogy society, said Kasman, who is the president of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Toronto. There are groups across the country in which members give regular workshops and seminars. In Montreal, for example, the Jewish genealogy group holds a monthly family tree workshop, which attracts between eight and 20 participants, said Diamond.

It’s at workshops and seminars where Diamond, the president of Montreal’s Jewish Genealogical Society and the founder of JRI-Poland, the largest online database of indexes to Jewish vital records, bursts a few genealogy myths.

One prevailing bubbe meise, he said, is that archival records were destroyed during the Holocaust. In Poland, for example, records were often located in town halls, which were protected because they were valuable buildings and usually were not razed during the war. In Poland, most records were moved to the state archives and preserved there, he said.

In one case that Diamond was involved with, a woman learned that her father had been married before the war and had a child, who didn’t survive. The birth records could not be found, but the Germans had stipulated that the child’s name be added to the parents’ records, which were located.

“She was able to have a grandchild named for her half-sister,” Diamond said.

A name was also the powerful impetus for Miriam Kochman, the grandchild of Holocaust survivors, to become involved in genealogy, simply because she wanted to learn more about the relative she was named for. As she began to research further, she found, to her surprise, a photo of another great-aunt, who her mother was named for. That great-aunt, who died during the Shoah, was working for the underground and was arrested by the Gestapo, Kochman learned.

“There were three photos. We never knew what she looked like until we found those photos,” she said.

Kochman’s family tree, which began with just 10 names, now has 250 relatives. Eventually she became so interested in genealogy, she enrolled in an online program, specializing in Canadian records. She is now starting a business as a professional genealogist.

“There are people who want to know what happened to (their families),” she said. “A lot of people don’t have the patience or time for it, that’s where I would come in.”

Every genealogist seems to have a story about a lost branch of the family that was found, or a surprising story that was uncovered by research.

Louis Kessler, who retired from a career at Manitoba Hydro, has been researching his family’s roots in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where his ancestors settled in the early 1900s. While looking for his great-grandfather’s citizenship records, he uncovered an astonishing tale.

At the time, settlers were required to live on and farm their land for three years before applying for citizenship. Kessler’s great-grandfather did just that, but when he applied, it was discovered that he had built his house 50 feet off the property. The three-inch file Kessler received from Ottawa showed his great-grandfather moved his house and farmed another three years before finally getting citizenship.

“This is what makes it so fascinating,” Kessler said.

Kessler began looking into his family history four decades ago, when an aunt visiting from the United States began drawing a family tree to show him how everyone was related.

That piqued Kessler’s interest in his extended family. His first step was finding his family’s immigration records on ship manifests and from there he began scouring old newspapers and applying for copies of birth, marriage, naturalization and death records, which included the story of his great-grandfather’s misplaced farmhouse.

With a background in computer science and statistics, he is currently developing software that will help people determine how they are related to those who they are matched with through DNA tests.

Sephardic genealogists have a luckier time of it than their Ashkenazic cousins, according to Jeffrey Malka, an American who is a renowned expert in the field.

Ashkenazim only started using surnames in the mid-19th century, while Sephardic surnames go back to the 12th century. As well, documentation in Spain and Portugal is “profuse,” he wrote in an email, with archives going back to the 12th century.

“In these voluminous documents – frequently over 500 per village or town – Jews are easily identifiable both by distinctly Jewish names and the suffix ‘Judio’ (Jew) after their names,” he wrote.

But for all genealogists, two developments have radically changed their searches; the first is the Internet, which puts records literally at searchers’ fingertips. The second is the DNA testing companies, which promise to find distant cousins, but in fact for genealogists have proven to be a mixed blessing at best.

Researchers may learn they have distant cousins, but often don’t recognize the surnames or birthplaces. Judith Kasman said that she’s met a few of her “DNA cousins,” but they’re still working on their family trees to see how exactly they are connected.

Neil Richler found a DNA cousin in Scotland who was also interested in genealogy and together they were able to see how their families connected. His sister recently met the cousin for the first time when she was in Scotland.

But where DNA testing has proven vital is in cases of adoption or hidden identities, said Stanley Diamond, who has used it to reunite long-lost family members. In one heart-warming case, using DNA resources, he helped a Russian woman, who had been a hidden child during the Holocaust, find dozens of family members in Israel, whom she met during a family reunion there.

Diamond said he has made 25 delicate phone calls, telling people they have a half-brother or child they never knew.

Earl Lesk, secretary of the Jewish Genealogical Society of British Columbia, found through DNA that he was related to Baron Joseph Gunzburg, a Russian financier and philanthropist. Gunzburg had several children, but was a father to dozens more who were born out of wedlock. Lesk, whose family came to the Canadian prairies in the early 1900s, was able to trace his DNA back to the French descendants of Gunzburg (and learned he came from the illegitimate side of the family).

“Until DNA, you couldn’t prove you were a descendant,” he said.

But even with online records and DNA searches, it’s not uncommon for genealogists to reach a dead end, which they call a “brick wall,” when they seem to go no further in their research.

But Lesk said that sometimes it’s simply a matter of being patient.

“The brick walls come down as technology improves. Tens of thousands of new records appear and are available every month.”

People are also continually posting their own family trees online, and sometimes a common ancestor will pop up, he said.

But sometimes luck and coincidence seem to play a part, as well. Richler was able to trace his ancestry back to a rabbi who lived in Ukraine in 1759, and rabbinic families were often well-documented, he said.

A cousin in Israel, who was also interested in genealogy, discovered the rabbi, Yehudah Edel, had written a commentary on the hagaddah. The family had it printed and published and they all used it at their seders, Richler said. “It was a real, tangible piece of history.”