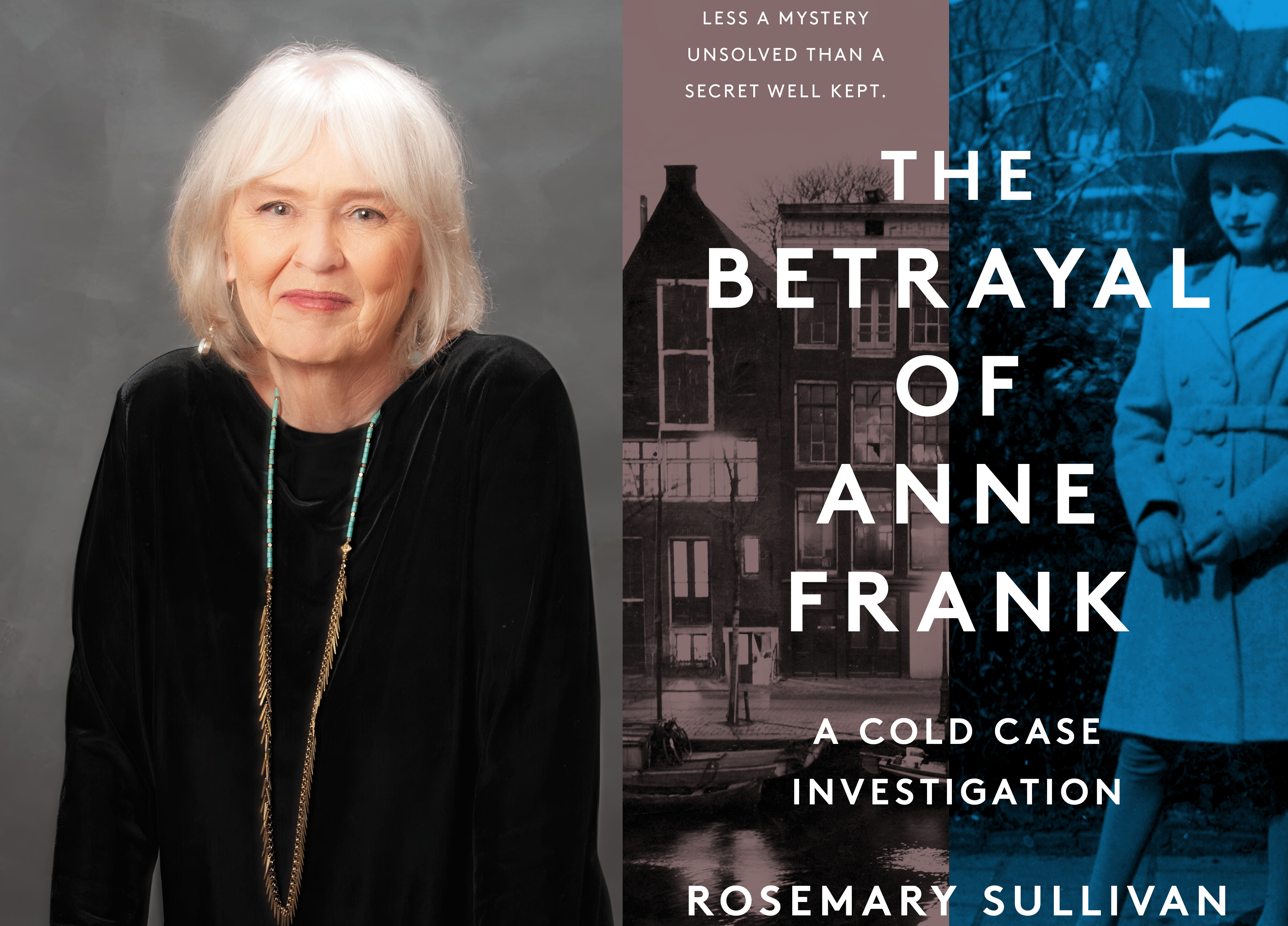

Editor’s note: Since our story came out on Tuesday, the Dutch publisher of the controversial new book about who betrayed Anne Frank has announced they are pulling all copies from bookstore shelves in the Netherlands. Ambo Anthos made the move following the release of a report by several historians in Amsterdam refuting the allegations made in the book by Canadian author Rosemary Sullivan.

In a news release, the publisher said:

“Tonight at the academic-cultural podium SPUI25 in Amsterdam, a number of prominent experts presented a very critical report on the investigation that is described in the book The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation. Based on the conclusions of this report, we have decided that effective immediately, the book will no longer be available. We will call upon bookstores to return their stock.

We would once again like to offer our sincere apologies to everyone who has been offended by the contents of this book.”

Ambo|Anthos Publishers

*****

A Canadian who was in hiding in the Netherlands during the Holocaust says there is no way the Jewish notary now blamed for betraying Anne Frank could have done it, contrary to the claims of a controversial new book by Canadian historian Rosemary Sullivan.

Leonard Vis offered this comment in response to the findings of a team of American and Dutch forensic experts, including a former FBI agent, all of which are profiled in The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation.

Published in January, it concluded the Franks’ secret annex in Amsterdam had its location divulged to the Nazis by Arnold van den Bergh.

Vis, a 91-year-old Jewish resident of Toronto, feels the researchers are guilty of “overt negligence,” even though he admits he has not read the book, which was based on the findings of a six-year research project.

But, in his view, the timelines don’t add up—and the evidence isn’t iron-clad. The investigators said they are about 85 percent certain the betrayer was Van den Bergh.

“You have to be 100 percent pregnant, not 85 percent, then nobody will discount that,” Vis said.

Focus on his hiding place in Laren

The Nazis raided the Franks’ hiding place on Aug. 4, 1944. That was nearly a full year after Van den Burgh, the supposed betrayer, also went into hiding with his wife—in the fall of 1943.

Vis has it on good authority that the notary’s family was hiding about 40 kilometres away from Amsterdam, in the small town of Laren.

And hidden in that same small town, around the same time, was Leonard Vis himself.

When the Nazis occupied the Netherlands in May 1940, Vis was nine. Vis lived with his parents and his brother and sister in Amsterdam. After the deportations to death camps started in the summer of 1942, his family split up and went into hiding.

“I was hiding there with 26 other people,” Vis told The CJN, describing his Laren refuge as “de hoeve,” which is Dutch for “the homestead.”

Although he did not know the notary at the time, and was not privy to where the notary was hiding in Laren, Vis has been working recently on the case with a Dutch professor: Aaldrik Hermans is compiling a list of all the Jews who were hidden there.

It is part of a report to be published on Tuesday during a public event at the University of Amsterdam.

Hermans and four other Dutch historians will be releasing what they are calling a “refutation” of the main arguments in the Canadian book—and also of the accusations against Arnold van den Bergh.

According to the book, Van den Bergh was a member of the Jewish Council in Amsterdam, the body set up by the Nazi occupiers to enforce the restrictive racial laws and the eventual round ups and deportations of Dutch Jews. The Germans shut the council down in September 1943, and Amsterdam was declared free of Jews.

Rosemary Sullivan has said that, as a council member, Van den Bergh had been able to protect himself and his wife and daughters from deportation up to that date. But after, with the vice tightening around him, he likely did pass a list of addresses to the Nazis to try to stave off deportation. She feels the notary was just as much a victim of the Nazis as anyone else.

“Who can judge somebody who knows that their family is going to be sent to an extermination camp, and you have a list of addresses, no names. You don’t even know what is behind those addresses,” Sullivan told The CJN Daily on March 8. “Possibly you convince yourself that people will have moved on.”

‘Painful’ to the Dutch Jewish community

The allegations that it was a Jewish notary who betrayed Anne Frank and her family have outraged many in the Netherlands. The City of Amsterdam has opened an inquiry into whether it can recoup the 100,000 Euros it granted to the investigators for the project. Some historians have discounted the book, noting that even the Swiss-based foundation that controls all the copies of Anne Frank’s diaries, declined to cooperate with the project.

The Dutch Jewish community has mounted an international campaign to have the book pulled.

Ruben Vis is the CEO of the Amsterdam-based Nederlands-Israëlitisch Kerkgenootschap, which represents 25 Dutch Jewish communities. He is also Leonard’s nephew, the son of Leonard’s brother Arthur. And he finds these “very painful” claims crucial to dispute.

“The British Daily Mail headlined that Anne Frank was betrayed by a Jewish notary and the word Jewish was in capitals. It’s unsubstantiated, it’s unfounded, so this is a colossal damage,” he said. “We have to understand, antisemitism didn’t suddenly stop in 1945. There is still antisemitism here in Europe.”

Ruben has been writing to media outlets around the world, and campaigning for the publisher to stop printing copies. He is perplexed that the main text of the book does not mention the town of Laren at all, where both his family and the Van den Berghs were in hiding. (The book does have the town’s name in three entries in the endnotes, as part of the title of some reference material.)

“Now, I know from my family experience, for my father, for my uncle, my grandparents and my aunt, who were all in hiding, it’s not the case that in August 1944, you’re going to the Nazis and tell the Nazis where you are and that you know of others who are in hiding,” he said. “Do you take that risk? Not at all. So it’s a very strange story.”

The Van den Bergh family, including three daughters, all survived the war. He died in 1950.

Criticism ‘misplaced’: Sullivan

Rosemary Sullivan calls the criticism of her book and of the forensic investigators methods: “misplaced.” She has also rebuked the Dutch publisher, Ambo Anthos, for including an apology to readers after the book came out.

“Now, if they believe that this book is insufficiently supported by evidence and has offended people, they should stop selling it,” Sullivan said.

On March 2, Sullivan was interviewed at a virtual event by Heather Reisman, the Jewish founder of the Canadian bookseller giant Indigo. It was Sullivan’s first opportunity to speak to the Jewish community across Canada about the reaction unleashed by her work.

Reisman described the book as “the one book you must read this year.”

For his part, though, Leonard Vis cannot understand how they would have concluded Van den Bergh had access to any lists of hidden Jews as late as in August, 1944, which is when the Franks were caught.

“The notary, Arnold van den Bergh, went into hiding right after the closure of the Jewish council [in 1943] because he no longer had a legitimate reason to stick around,” Vis said. “There was absolutely no way he could know where Jews were hiding.”

Vis does raise one interesting possibility. As a notary, he could have helped his Jewish clients write their last wills, before they were put on the train to Westerbork, the deportation transit camp near Amsterdam. These wills would have had addresses on them, and would have had to have been registered, so there could be historical records available to check.

“That should be investigated,” Vis said, as it might clear up whether the notary had records of these addresses in his possession.

Legacy of betrayal

The Betrayal of Anne Frank paints a picture of the occupied Netherlands as a country where its 140,000 Jews didn’t have a strong chance of survival. About three-quarters were murdered in the Holocaust. Of the 23,000 who were in hiding, one-third were eventually betrayed.

These are statistics which Rosemary Sullivan believes need to be addressed by the Dutch people today, as they sent the most Jews to their deaths of any Western European nation during the Holocaust.

The wartime legacy resonates deeply with Leonard Vis: he was also betrayed while hiding in Laren.

He thinks he knows who did it, but to this day he is not sure. He once told a Canadian school group that their betrayer was the jilted ex-girlfriend of his host in Laren, who did it out of revenge. However, he told The CJN a non-Jewish man was to blame.

The Gestapo arrested the 26 people in that house on Sept. 30, 1943.

It happened to be the first day of Rosh Hashanah. Vis had turned 13 a few days earlier. After ten days in a holding centre inside a theatre, on the night of Yom Kippur, he was put on a train.

The resourceful teenager jumped off, and was not injured. He walked back to Amsterdam, where he hid with another Dutch family for the remainder of the war.

“Holland was a country of very loose lips, of vengeance, of vendettas,” Leonard Vis said “They didn’t need Arnold van den Bergh.”

There were a few Jews who sent notes to the Nazis, including the notorious Anna van Dijk—she was executed in 1948 for her murderous collaboration.

In Amsterdam, Ruben Vis is hoping this week’s refutation report will have the desired effect of slowing book sales, and reversing world opinion about who betrayed the Franks.

Otherwise, he fears it will become more ammunition for conspiracy theorists and Holocaust deniers.

“For such a public figure as Anne Frank, we want to know all the circumstances. We want to know who her friends were. We want to know how she did in school. We want to know what she wore, what she loved, who she loved.

“Of course, you want to know everything about this. But please keep to the truth and don’t pinpoint or don’t finger point to someone I must almost say has an alibi.”

Ruben’s uncle expects the new report will shed more light on the truth about Arnold van den Bergh’s activities during the war, especially while the man was in hiding in the town of Laren. Leonard said that the Dutch researcher, Aaldrik Hermans, has been trying to reach the people who sheltered the now infamous Jewish notary during the war. They now live in Australia.