When schools and workplaces were suddenly shut down in March 2020 as the COVID pandemic reached Canada, the staff at Ve’ahavta faced a predicament. They were partway through teaching in-person, nine-week-long courses on work and life skills, which the Jewish humanitarian non-profit offers to homeless and vulnerable people. But fewer than half their clients had computers to access the program online. And with libraries and coffee shops closed, places where their clients usually found free Wi-Fi were also unavailable.

So the agency gave their clients smartphones with a few gigs of data. It wasn’t even enough data for Zoom classes, but it would do in a pinch, the staff figured. What happened, however, was surprising, Ve’ahavta executive director Cari Kozierok recalled. Every one of their clients finished the course and graduated. Typically, she said, about 82 percent of participants finish the course.

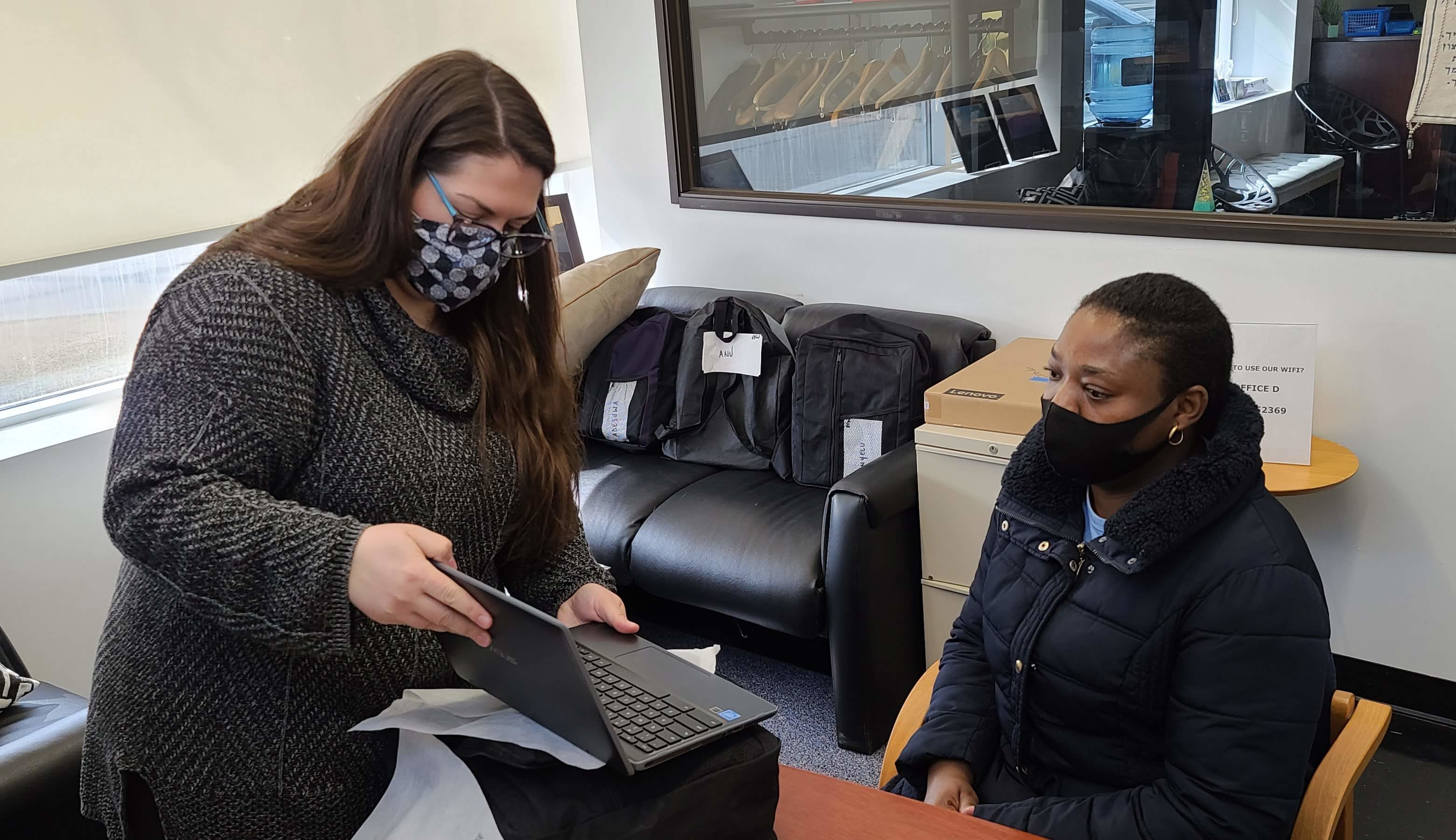

The following semester, Ve’ahavta gave participants in its Skills Academy and Building Foundations for Women programs inexpensive laptops, if they needed them. In some cases, the agency paid for internet in people’s homes and boosted WiFi access in women’s shelters. This time, 100 percent of participants completed the program.

Intrigued, Ve’ahavta commissioned a research study to examine the impact of giving clients access to the digital world.

“The folks that we’re working with have been through some difficult times and struggle with all kinds of things,” Kozierok told The CJN. About 30 percent of participants were living in shelters. Some clients were travelling an hour and a half to get to classes, she said.

“Our best guess is that removing the physical barriers enabled people to continue with the program, even when they were having a particularly difficult time personally.”

Over the past year, Ve’ahavta has given their clients 135 digital devices—phones and computers with internet access—bridging what has been called the “digital divide,” the economic and social gulf between those who have the ability to access the Internet and those who don’t.

Ve’ahavta’s study found that the benefits went far beyond the 100 percent graduation rate. Many of the participants had never turned on a Chromebook before, but with intensive coaching, they learned to use the device, Kozierok said.

Nearly every participant in the survey—96 percent—said they intend to take more courses online, and 79 percent said they were applying for or searching for new jobs.

The devices had a ripple effect, with 71 percent of participants helping friends and family access or use the internet, while every person surveyed reported improved mental health.

“I don’t believe it’s fully possible to engage in modern society without those devices and without having that Internet connection,” Kozierok said. “Everything I do is done online, everything most of us do is done online.

“For people not to have these devices and that (internet) access, means they are cut out of all sorts of aspects of normal life that we all take for granted.”

Verna Oppong, 60, who received a Chromebook from Ve’ahavta when she enrolled in the skills development class, said connecting online has given her access to support she never had before.

A retired personal support worker, Oppong found that the anxiety and depression she had long struggled with ratcheted up during the early days of the pandemic.

Going online “took me out of isolation,” she said. “It gave me the opportunity to connect and meet new acquaintances, and meet like-minded people.”

She now participates in a women’s support group and has taken classes at George Brown College.

“Even though it was a pandemic, I do not feel isolated. I am more busy than I was pre-pandemic,” she said. “This has opened up a whole new world for me.”

Social workers at Toronto’s Jewish Family and Child Service faced similar challenges as did Ve’ahavta at the start of the pandemic.

With staff working from home, the agency worried how it would keep track of its most challenged clients—those who had no fixed address and who used to make unscheduled drop-ins to its offices.

“Now that that option is no longer available to us, it was very important for us to somehow keep in touch with them,” said Noa Ashkenazi, manager of poverty reduction at JF&CS.

The solution was to distribute cell phones and pay for a data plan so the social workers could keep tabs on their most vulnerable clients.

Before the pandemic, JF&CS usually gave computers to people who needed them for school or job searches, said Ashkenazi. “Now we give them to whoever needs them, because we understand the importance of Zoom and online communication.”

Schools, both public and Jewish day schools, have supplied Chromebooks to students who had to move to online education, leaving JF&CS to focus mainly on adults.

As the agency transitioned its support groups and counselling online, it purchased laptops and cellphones for the most socially isolated clients, sometimes making arrangements directly with the telecom company to gain internet access.

“We knew we had no choice,” said Monica Auerbach, director of services. “We can’t have people so totally isolated. They couldn’t even go to their Tim Hortons, which was their only socialization for some of them.”

Since March 2020 and the start of the pandemic, JF&CS has purchased 66 devices for clients—phones, computers and home lifeline alerts—and spent about $32,000 on technology. Private donors who provided funds with no strings attached have helped with some of the extra expenses, Auerbach said.

During the pandemic when hospitals and shelters have been off-limits to visitors, donated cell phones have become a lifeline, Ashkenazi said.

“We provided a phone to a client who was in hospital and was very isolated and had no family. We couldn’t visit, so for us to talk with him and learn what was going on, was priceless,” she said.

“This is technology but it translates to the most basic kind of kindness, compassion and care.”

Nearly every service JF&CS provides, even its annual Hanukkah party, has gone virtual. The agency’s tax preparation clinic, which used to be in-person and served hundreds of people, was done entirely by phone and Zoom this year, said Ashkenazi.

“A lot of our clients rely on government benefits, which they are not entitled to unless they file their taxes,” she said.

“Some clinics shut down, not all of them were able to transition online. For me, that hundreds of people were able to file taxes this year was a huge success story.”