Henry Wellisch survived the Holocaust because of an extraordinary run of good fortune and a restrictive policy on immigration to British Mandate Palestine, that saw him exiled to the tropical island of Mauritius.

The centenarian, who now lives in Toronto, reflected on the twists of fate during the war years. “It wasn’t the best place to be,” he told The Canadian Jewish News about his years in Mauritius, “but I was better off than the Jews who stayed behind in Europe.”

Born in Vienna, Wellisch was living with his parents Emil and Jolan in the Jewish neighbourhood of Leopoldstaat. Then in May of 1938, the Nazis marched in, and “all normal life came to an end.”

His father ran a store selling livestock fodder, but shortly following the German invasion, a Nazi officer showed up, and demanded the family relinquish the store for military use (the army still had equestrian units). His father instead opted to sell the business to his non-Jewish competitor at a loss, rather than release it to the Nazis.

From their apartment, the family witnessed the synagogue burnings in Kristallnacht that November—a bleak omen that triggered their decision to flee to Palestine.

They first got to Tulcea, Romania, and from there, boarded the Atlantic, a ship with a Greek crew, flying the neutral Panama flag. “The conditions were bad. I didn’t shower for a whole month. We only had soup occasionally. When we stopped at Turkey and Greece, the Jews there gave us bread and water, but it was crammed. People were sick and some died,” he said.

The ship would tilt, and passengers had to constantly move to the right or left side to prevent it from toppling over.

Then there was a mutiny on the boat when the supply of coal ran out. The passengers made a citizen’s arrest on the captain and desperate to keep the ship moving towards its destination, tossed whatever wood they could gather from the ship into the furnace. This lasted for three days.

Not far from Haifa, the British intercepted the Atlantic, transferring the refugees to another ship, the Patria, where they faced impending deportation. But the Jewish militia, the Haganah, opposed the move, and planted a bomb aboard hoping to disable the ship and prevent it from leaving the port.

The blast was miscalculated and blew a hole in the hull, sinking the ship in minutes, killing 267 people and injuring 172.

To deter further migration, the British interred some of the survivors, including Henry and his family, on Mauritius. The island eventually held 1,588 Jews.

The prison was managed by a commandante named Armitage, unpopular among the inmates for taxing 10 percent of what they received from their relatives abroad, “and they didn’t have much to give either,” Henry exclaimed.

Still, via the Red Cross, he was able to correspond with relatives in Austria for another year or two, before they were captured by the Nazis. His mother’s sister lived in Hungary, and he corresponded with her family until 1944. Some of these relatives survived the war and later moved to New York, he said.

While in Mauritius, the Wellisch family was aware of what was happening in Europe, as they received newspapers from South Africa, the nearest Jewish community. Henry also heard news from BBC radio in English and German when he worked in the radio room. “It was not maximum-security prison, but we were very restricted,” he said.

He also worked as a carpenter, learning the trade from a Mauritian at the camp. “I had a lot of free time, and in prison, you have to do something to be active or you go crazy,” he recalled.

He learned English and Hebrew by reading books from the prison library and a local priest gave him a Bible in English.

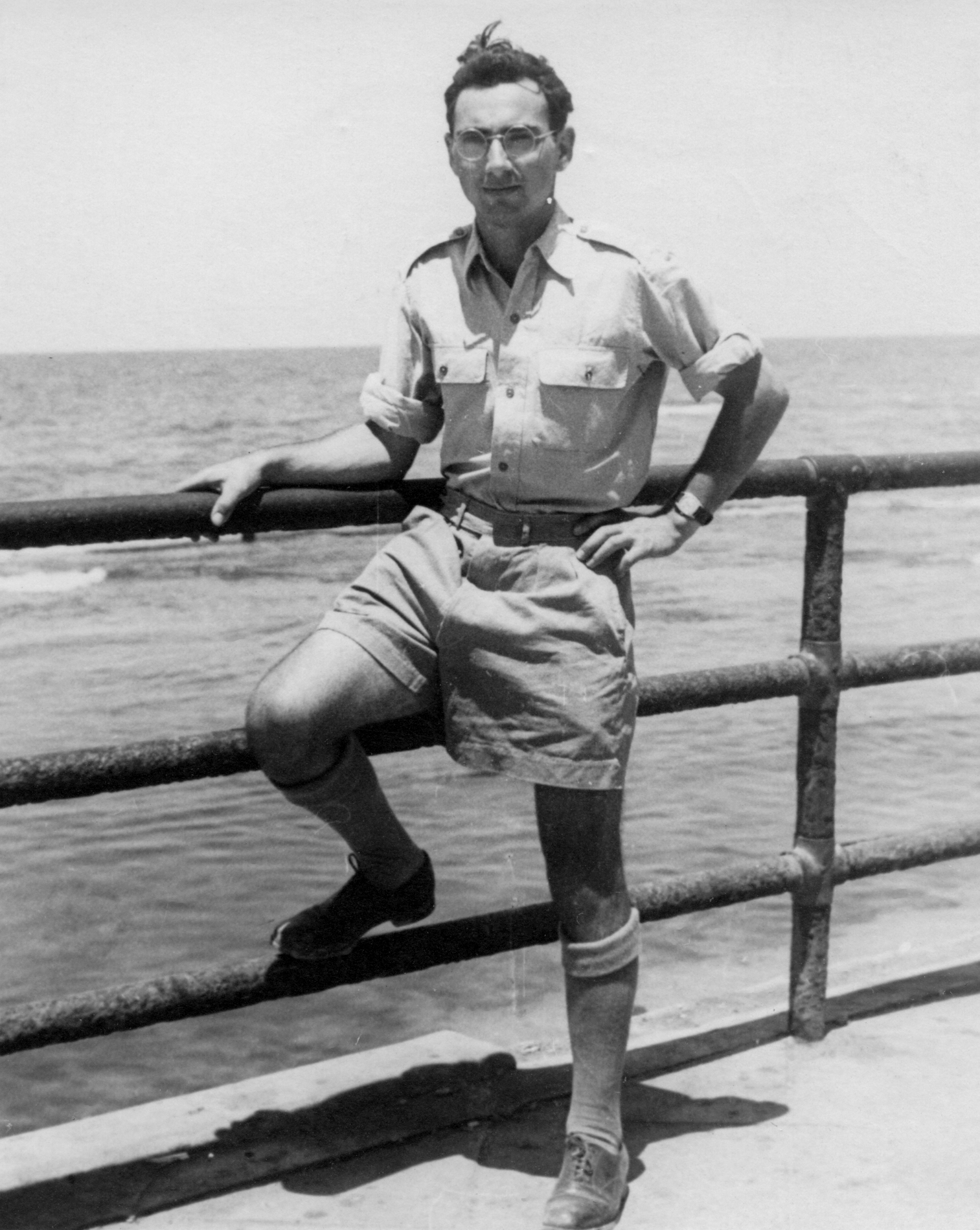

In 1944, Henry, along with 50 others, were able to volunteer for the Jewish Brigade to fight in the war effort. They were taken to Egypt for four months of basic training, and then deployed in the Netherlands and Belgium. After the war, he was able to receive leave to be with his parents.

Most people in the Mauritius camp emigrated to Israel, including his family. Since he already had military experience, he enlisted in the IDF, and witnessed Israeli independence in 1948 firsthand.

Four years later, in 1952, he and family, unable to find work in the newly formed Jewish state and disliking the Middle Eastern climate, moved to Montreal. An uncle there hired him as a technical draftsman.

In 1965, Henry married and had a daughter with his wife Natalie, and in 1969 he moved to Toronto, where he now lives.

Reflecting on his life and the historic events he lived through, Henry says simply, “I’m glad I finally moved to Canada. It is very nice here.”