The typical arc of immigrant groups goes something like this. First arrives the impoverished vanguard, fleeing famine or persecution. Without proper language skills or professional credentials, these pioneers take whatever menial jobs will allow them to build the foundations of a stable working-class life. Then comes the next generation, a bilingual cohort that bridges the culture of old and new, as its members stake their place in higher education and white-collar workplaces. Then a wealthier, fully assimilated third generation, one that enters society’s most respectable neighbourhoods and professions, and which knows its roots only from photographs and the stories of wizened old relatives. It is a steady, linear, ascending economic progression that might be symbolized graphically by the forward slash character on your keyboard.

This is the image of Jewish progress I internalized during my childhood. Indeed, the forward slash conception was so widely accepted as to become the subject of satire. One of the favourite books in my Montreal household was a comic called Up From Seltzer, authored and drawn by Peter Hochstein and Sanford Hoffman respectively, depicting the progression of Jewish life through a series of four panels, each corresponding to a different generation. Under the heading, “Jewish beverage of choice,” for instance, was a picture of a first-generation couple, straight out of the shtetl, extolling the delights of seltzer water. Then comes the second generation, rye drinkers looking like something out of a 1950s Jewish cottage club. Followed by the third: “Pouilly-Fuissé, well-chilled.”

But once you start researching the history of Jews in Canada – especially Jewish business and professional life – it becomes apparent that the forward slash model is ahistorical. In truth, the path of Jewish economic fortunes in this country more closely resembles the letter U. We started out strong, but then took a dip when our community became dominated by waves of poor arrivals in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is the economic ascent of this latter group, which began more than a century ago, that forms the isolated basis of our forward slash understanding. But to get the full story – including the leftmost side of the U – one needs to go back to the days of muskets and wooden ships.

* * *

There is some debate about who gets the title of Canada’s first permanently settled Jew. The most commonly identified candidate is Samuel Jacobs, a schooner owner who supplied the British with liquor in the 1750s, and who eventually settled in Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu, northeast of Montreal. But it’s hard to say definitively, because many travellers came to the new world with the intention of throwing off unwanted connections with their birthplace and creating new identities. In New France, where Catholicism was the only recognized creed, Jews were technically not even allowed to set foot aground. And the genealogical records contain a number of suspiciously Jewish-sounding families who showed up at Quebec churches to get their children baptized.

Among the British, however, attitudes were more relaxed, especially toward those, such as Jacobs, who could help support the colony and the war effort. In time, many of these families settled down in Halifax, Montreal, Trois-Rivières, Quebec City, Winnipeg and points in between. The number of Jewish families in Canada remained very small till the end of the 19th century. But these early Jews were disproportionately represented among the wealthiest and most influential members of Canada’s commercial class – typically specializing in areas requiring ready access to capital, such as banking.

Some of the early Canadian Jewish entrepreneurs were true frontiersmen – venturing deep into the wilderness to trade with First Nations. (A 1959 Maclean’s retrospective on the first two centuries of Jewish life in Canada saluted “veteran fur buyer Jack Leve of Sudbury, [who] spent 26 years in the bush, speaks fluent Ojibway and is one of the biggest buyers of raw pelts in northern Ontario and Quebec.”) Like many modern immigrants to Canada, these Jews flourished in large part because they were the same self-selected go-getters who had taken the risks associated with crossing an ocean in the first place.

If that was where the Canadian Jewish genesis story ended, this would be a boring essay – for the Jewish community we would be celebrating would be tiny in size and almost completely assimilated in character. But in the early 1880s, tragedy intervened, in the form of anti-Jewish pogroms within Russian-controlled areas that span modern Belarus, Lithuania, Moldova, Ukraine, Latvia and Poland. The first Canadian census, taken in 1871, found just 1,115 Jews. Over the next four decades, this number would grow by two decimal orders of magnitude, as Europeans fled their ancestral lands and headed west.

To the small but largely wealthy population of established Canadian business owners, these newcomers seemed from another planet, and the cultural gulf between the two groups would not be bridged until the second half of the 20th century.

The opposite of Jacobs and his refined ilk, these were peasants, farmers and labourers who grew up in ghettos or impoverished farming communities. The Canada of the late 19th century was a free, capitalist society where Jews could serve openly as mayor or police chief. Yet many of the Jewish immigrants now coming to Canada had come of age in (literally) feudal societies.

The new arrivals were not bereft of useful job skills, however. As with Mennonites and Ukrainians, many of these Jewish immigrants ended up in Western Canada, raising crops in soil that was not so different from that they’d sown in eastern Europe. And true to the stereotype embedded in such characters as Motel Kamzoil from Fiddler on the Roof, there were plenty of Jewish migrants competent in tailoring and needlecraft – fields that eventually would become massively scalable as clothing production moved from homemade and cottage-industry garments to industrial mass production.

At the time, the Canadian frontier was beset by labour shortages in many areas. In his excellent 1990 book, A Coat of Many Colours: Two Centuries Of Jewish Life In Canada, Irving Abella notes that the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), in particular, afforded plenty of opportunities, along with a surprisingly wide range of what we would now call “reasonable accommodations” for diverse cultures: “Desperate for workers, the CPR was prepared to hire any man who could withstand the rigour of laying tracks, digging trenches and building bridges across the prairies. It even provided the observant Russian Jews with kosher food and their own sleeping cars, exempted them from working on the Sabbath and allowed them to return to Winnipeg for religious holidays.”

By the early decades of the 20th century, the story of Jewish economic history in Canada becomes broken up into sub-narratives defined by geography, industry and social class. Generalizations become more difficult. The cheek-by-jowl community of ambitious urban Jews described by Mordecai Richler in The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz is a world apart from that depicted in black-and-white photographs of Jewish prairie farmers, rugged specimens who obeyed the same seasonally dictated patterns of workaday agricultural life as their gentile neighbours on the other side of the property line.

Many of the most successful Canadian Jewish entrepreneurs from this period reinvented themselves with bewildering speed over the course of their careers. In the Pale of Settlement, sons typically followed the path of their fathers from one generation to the next. But in Canada, Jewish entrepreneurs found a country in the throes of both geographical expansion and mass-retail transformation.

In 1889, a Moldovan tobacco farmer named Yechiel fled to Western Canada, where he operated a homestead, sold firewood and whitefish, traded horses and then got started buying hotels and running bars. Shortly after this death, his son Samuel set up the Distillers Corporation in Montreal. Their last name, of course, was Bronfman.

READ: COUNT ME AMONG JORDAN PETERSON’S JEWISH SUPPORTERS

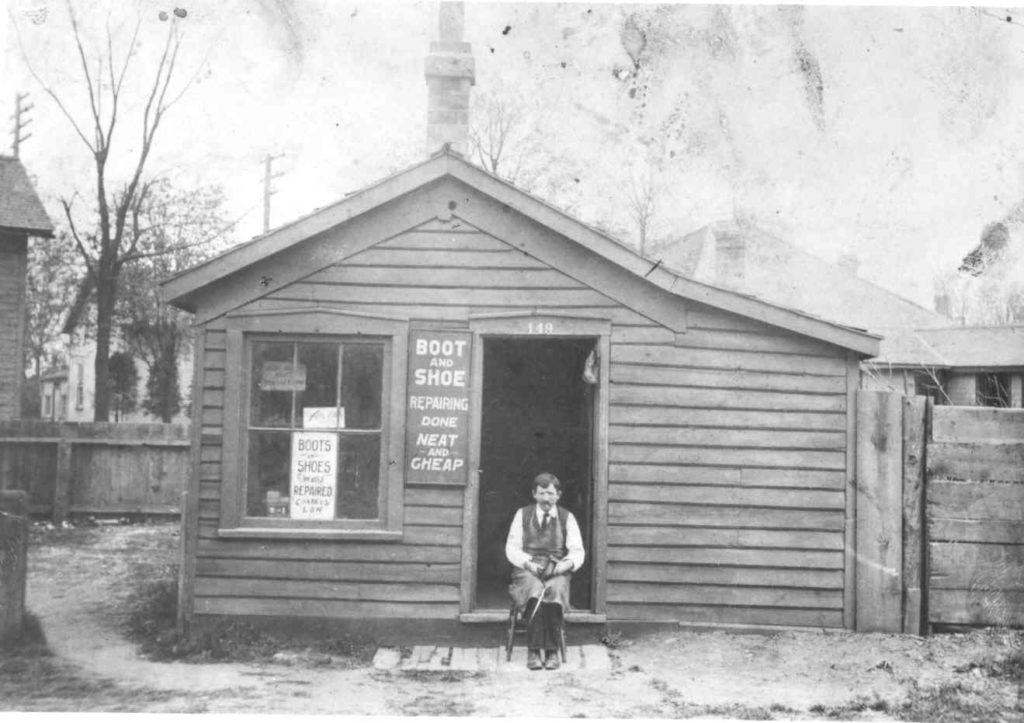

In many small communities, Jewish businesses sat at the literal nexus of business life, operating small stores in rural or semi-rural communities that served as a combination of miniature shopping mall, post office, meeting hall, bank and translation service. In some ways, this was a natural fit for these new Jewish immigrants, a polyglot minority that had found ways to carve out a commercial niche within the societies of eastern Europe. But now, in Canada, they could practise their trade without pogroms and all the other crushing effects of institutionalized anti-Semitism. For a Jew to become flamboyantly successful in Europe was often to invite potentially murderous jealousy. Anti-Semitism was hardly unknown in Canada. But at least there were no Cossacks.

The children of immigrant Jewish farmers and tailors entered every corner of Canadian industry. By the 1930s, Jews already were becoming so successful in prestigious fields that universities began to limit their numbers. In a 1939 study performed for the Canadian Jewish Congress, scholar Louis Rosenberg wrote: “It is often taken for granted by Jews and non-Jews who discuss the occupational distribution of Jews, that there is an abnormally large trend of the Jews towards the professions, and some have even gone so far as to justify the many devices, open or camouflaged, which are used by professional schools and colleges to limit the number of Jewish graduates in certain professional fields, or to suggest that Jews themselves should adopt a sort of ‘self-denying’ ordinance and limit the number of Jewish students in training for the medical and legal professions.”

Rosenberg’s statistical portrait – entitled A Social And Economic Study Of Jews in Canada In The 1930s – is notable for its extraordinary detail, breaking down Jewish representation in such tightly delineated categories as “Candy and Confectionary,” “Florists and Seedmen” and “Drugs and Toilet Preparations.” Given the stereotypes of the day, it makes sense that the author was particularly eager to note that “Jews do not dominate the retail or wholesale trade in Canada.” But his statistics do show that some specialties truly did attract a strong Jewish concentration. Half of Canadians working in “second-hand goods” stores – i.e., pawn shops – were Jews. In the fur business, the figure was 28 per cent. Men’s clothing: 24 per cent. Women’s clothing: 20 per cent. Rosenberg noted that only 2.2 per cent of Jews were engaged in “fee-earning professions” such as law and medicine – though that was still more than double the overall Canadian rate of one per cent.

In total, Rosenberg found, 28 per cent of gainfully employed Canadian Jews worked in the field of “merchandising retail,” compared with seven per cent of all Canadian workers. In wholesale, the figures were four per cent of Jews, compared with one per cent of all Canadians. Among “peddlers, canvassers and newsboys,” it was four per cent versus one per cent. Among clerks, it was 10 per cent versus six per cent.

Importantly, Rosenberg takes pains to break down these historical trends in business and professional life for both men and women. Early accounts of Jewish life in Canada tended to focus mostly on family patriarchs and their (male) heirs, with wives and daughters thrown in as supporting cast. By the 1930s, such an approach was untenable, as women now accounted for almost 20 per cent of all “gainfully employed” Canadian Jews in the retail trade. Women also accounted for more than 70 per cent of all Jews working as clerks.

That said, Jewish women still were largely confined to many of the same stereotypically female occupations as their gentile peers. “Among every 1,000 Jewish women and girls engaged in retail merchandising in Canada in 1931,” Rosenberg notes, “there were 819 saleswomen,” few managers and just five “hawkers and peddlers.”

* * *

Rosenberg published his study in 1939, the same year my mother’s father, Theodore Richmond (known to one and all as Teddy), wed my grandmother, Florence Golden. (Their marriage on Sept. 3 was a sombre affair, with the dancing interrupted by an announcement that Britain and France had declared war on Nazi Germany.) No single man can stand in for the flourishing of Jewish business life during the 20th century. But there aren’t many who could make a better run at it than my grandfather, whose business success helped lay the foundation for the opportunities that my family and I still enjoy to this day.

Teddy was the youngest of nine children – four of whom had been born in Poland, before his parents emigrated to Canada after the First World War. As a child, he worked as one of those “peddlers” Rosenberg catalogued, sometimes helping his father sell odds and ends from a horse-drawn cart. Eventually, he got into the scrap metal trade – which may not sound like a route to riches.

But in 1945, opportunities arose for Canadian entrepreneurs to buy old Second World War tanks and military residue stockpiled in obscure depots such as Guam. In time, Teddy got into the production of tubular steel (which took off thanks to the rise of cheap, machine-made furniture), plywood bookcases, picture framing, do-it-yourself television-tube testing, photo developing and coin-operated laundry machines.

My grandfather died more than 30 years ago, but many Torontonians still remember him fondly. (During a Facebook discussion about an unrelated topic in 2018, former Ontario premier Bob Rae said to me, out of nowhere: “Your grandfather was the funniest after dinner speaker I ever heard – a comic genius.”)

He was the very prototype of the successful hustler made good – a man with very little formal education, but a ton of moxie and charisma, plus, most importantly, a keen eye for grass-roots business opportunities.

One of my last memories of Teddy originates with the day I dragged him to the McDonalds restaurant at the corner of Eglinton and Bayview avenues in midtown Toronto. A creature of habit, Teddy had eaten at the same handful of delis his whole life, never once passing under the golden arches. The place was bustling, and his eyes went wide as pickle slices as he muttered, to no one in particular, “Look at all these people.” As he trailed off, his eyes glanced up at the overhead menu with the prices listed, and I could see he was running the numbers in his head.

But there was a dark side to Teddy’s life. Unlike members of my own generation, or even that of my parents, my grandfather had no safety net, no well-heeled older relatives to assist as a last resort.

If his businesses failed, that was it – he’d be out on the street. Others would have suffered, too, since various friends and relatives depended in direct and indirect ways on his largesse.

Like many other Jewish business leaders, Teddy took seriously the concept of tzedakah, and extended his charitable efforts well beyond kin – and was named man of honour at the 1981 Negev Dinner in Toronto. The commemorative book from that gala contains dozens of photos of Teddy leading good works in both Canada and Israel. Teddy’s example shows us, among many other things, that the rise of Jewish business and the rise of Jewish civil society and public welfare in Canada were inseparably intertwined.

In the early 1950s – no one is sure what year exactly – my grandfather collapsed in midtown Manhattan, struck by the first of the heart attacks that eventually would take his life – just blocks from where I would one day work as a tax lawyer, thanks to the education his hard work would help make possible. At the time, he was heading to a meeting with U.S. business partners keen to develop a new, more efficient method that Teddy had invented to sell laundry detergent alongside coin-op laundry operations.

It wasn’t the walk that did him in – but the insane stress. My grandfather is remembered fondly as a family man, but the truth is that he was workaholic, consumed by a fear of failure, and often riddled with anxiety over the massive debt he sometimes took on to start new projects. He drank and smoked heavily, and would collapse instantly into sleep as soon as he sat down in his living room after 12-hour days at the office.

“The main character in that musical, What Makes Sammy Run?, Sammy Glick – my father was like that,” recalls my aunt Anne Golden. “He had endless ambition. We’d be in the money one day, and then out of it the next. If something went wrong at work, he’d come home and suddenly all of our piano lessons were canceled. It was a roller coaster. But when he was doing well, every night was New Year’s, and Chinese food on Sundays.”

My grandfather’s identity as a Jew was a huge source of strength in his life. He was not unusually devout, but he often spoke seriously about God, and about the need to protect and strengthen the Jewish community. Zionism was part of this. I have a distinct memory of being 12 years old, travelling in his big grey Cadillac from a restaurant back to his condo in Miami Beach, Fla. I was babbling sanctimoniously about some half-understood news I’d heard about the Palestinians, and opined vaguely that Jews were acting like Nazis. Teddy did not deliver unto me the full force of ridicule that this comment deserved, but he did provide a short and stern speech about what real Nazis were like – the ones who had killed his family members, my family members. We all like to pretend that we arrive at our opinions from first principles, without any programming from others. But I will admit that much of what I have written about the world during the course of my career originates in that two-minute oration on Collins Avenue, though he himself probably had forgotten all about it by the time he flipped his keys to the valet at the Carriage House.

One thing my grandfather rarely spoke about – to me, at least – was anti-Semitism in Canada. As someone who grew up in a Toronto ghetto, among immigrants who’d grown up in societies where many gentiles truly believed that matzah was made with the blood of gentile children, the fact of anti-Semitism was not something that required proof or explanation. But the mostly genteel separate-but-nominally-equal anti-Semitism that Teddy experienced in Canada during his adult years – while abhorrent by today’s zero-tolerance standards – paled in comparison to the exterminationist horrors that reached their crescendo during his own lifetime.

As a businessman, my grandfather operated in a Toronto environment bounded on all sides by unspoken walls. There were bankers who would lend to Jews and there were bankers who didn’t. There were buildings where a Jew could set up his business, and those where he couldn’t. Business partnerships were formed largely on a Jew-to-Jew basis, not because the law required this, but because this was what was done. This was in keeping with the same pattern that had played out for centuries: Jewish entrepreneurs suffered from their exclusion to broader business networks, while also benefitting from the strong bonds of trust generated within the stigmatized community.

What was new for Jewish business leaders in Canada is that this new country – not being contaminated with the same murderous folk varietals of Jew-hatred long virulent in Europe – did not rise up in pogroms against Jews when jealousy at their success and wealth tipped into hysteria. That is because Canada was, from its origins, a capitalist country where it was seen as right and natural that industrious men should profit from their genius – while the Pale of Settlement was still, in its soul, a pre-modern world where it was unnatural and suspicious for any person to rise above his neighbours.

* * *

Of my grandfather’s seven grandchildren, most of us being now in our mid-to-late 40s, only two followed in his footsteps as businessmen: my cousins Daniel and Robbie Kumer. And in both cases, their

experiences illustrate how much times have changed for Canadian Jews in the business world since my grandfather’s days, albeit in different ways.

Danny (as everyone in the family calls him) has put down stakes in the field of cryptocurrencies – a milieu in which markers of personal identity, including religion, typically are irrelevant, because the product is virtual, and most business operations are conducted in entirely disembodied electronic form. For online entrepreneurs, one’s religious background is about as meaningful as one’s astrological sign. To quote the most successful cartoon in the history of The New Yorker, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

Robbie, on the other hand, operates in the more traditional field of real-estate investment. Having spent the last 25 years methodically riding the relentless growth in the Canadian real estate business, he currently serves as chief investment officer for KingSett Capital – a leading private-equity real-estate investment business.

When I visited Robbie at his office for an interview, I asked him to help me close the loop on our grandfather’s business odyssey by reflecting on how his own Jewish identity has shaped his career. The answer was, in short, that it hasn’t. And a look at the “Who we are” section of the KingSett Capital website suggests why: like most large, successful Canadian businesses, it is a melting pot of skin hues and surnames, Jawed alongside Johnson, Ravindrakumar alongside Rose, Skutelsky alongside Smith.

“No one here knows or cares that I’m Jewish,” Robbie told me. “The only time it might come up is if there’s a Jewish holiday. I’m 43 and I’ve never once encountered anti-Semitism in my professional life. If anything, sometimes my colleagues are remarkably sensitive. Like a while back, when there were news reports about white supremacist mobs in the United States, a colleague told me he was distraught on my behalf, even though I hadn’t really thought about it much from a personal angle.”

I see Robbie at least once a year. He and his wife Barbara traditionally have hosted a Passover Seder at their house. Being a more observant Jew than me, Robbie is capable of leading these services personally, in some cases pushing them past the point of my own endurance for prayer and ritual.

And in this compartmentalization – celebrating Judaism at home, while being free to transcend matters of faith in one’s business milieu – he arguably is living the ideal of true liberalism that countless generations of Jews have pursued. It stands as a testament to the success of our Canadian national project that such a life is possible for descendants of every Samuel, Yechiel and Theodore who put down roots in this country, in search of a better life.