Systemic racism against Canadian Jews boiled over on Aug. 16, 1933.

It was the date when Jews and their allies from Toronto’s immigrant communities fought against Nazi-inspired youth and others of similar disposition in one of Canada’s worst outbreaks of racial violence.

Canada now is almost unrecognizable from Canada then. But there are still important lessons from the Christie Pits Riot, 88 years later.

When my father first immigrated to Winnipeg, he was barred from many private clubs, some golf courses, certain employment opportunities, and even from living in certain areas.

But this was hardly unique to one city in Canada.

In the first half of the 20th century, antisemitism was a socially acceptable, inseparable part of mainstream society. Jews were relegated to second-class citizens.

Businesses refused to hire them, universities restricted their enrolment, and entire neighbourhoods prohibited the sale or rental of housing to Jews.

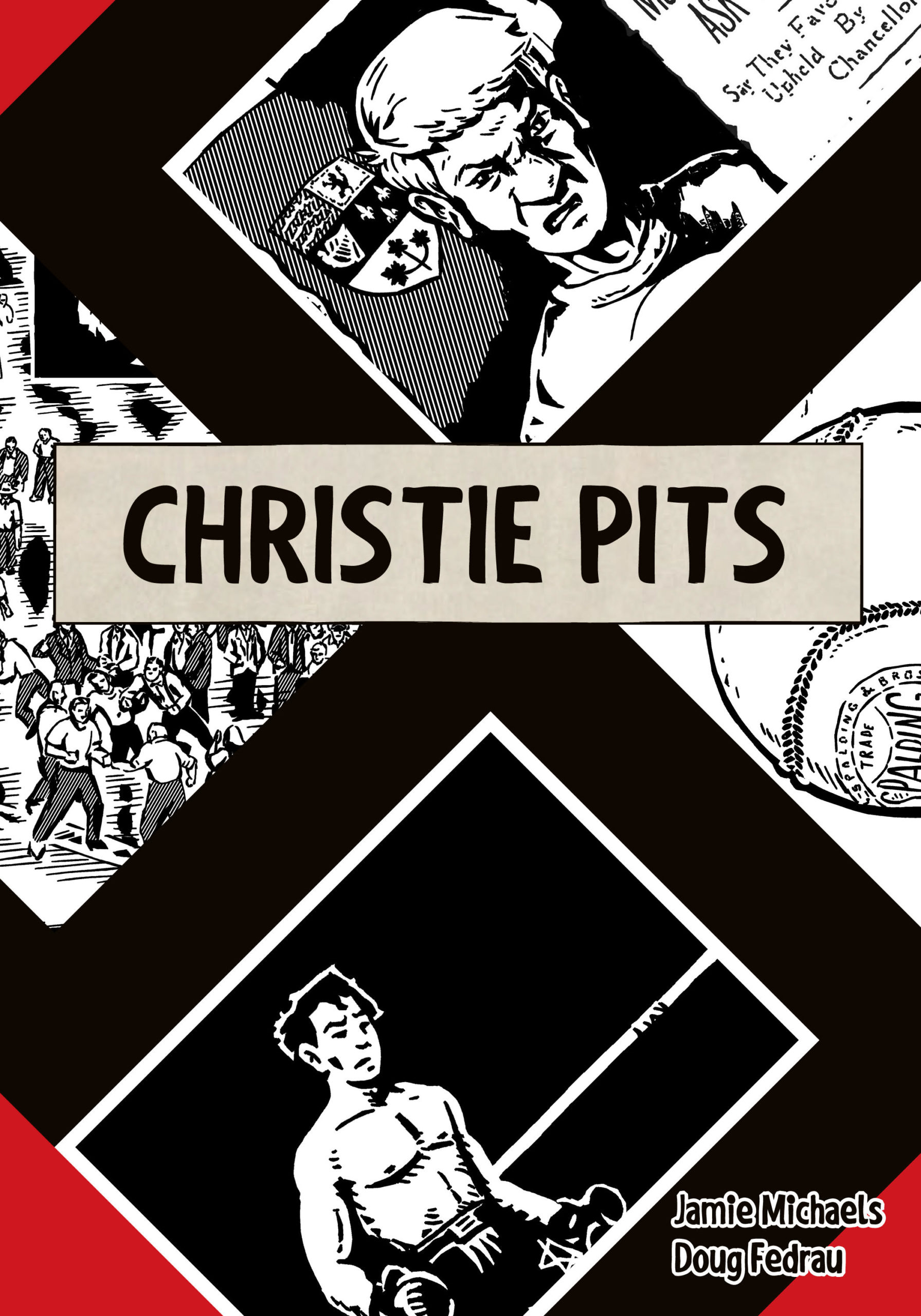

In the Toronto of 1933, headlines about the formation of “Swastika Clubs” appeared in major newspapers across the city, shocking the Jewish community. Hitler’s rise to power in Germany, coupled with shocking reports of Nazi atrocities, left little doubt as to what the swastika stood for.

The predominantly Jewish Harbord Playground baseball team met local rivals St. Peter’s for a mid-August playoff game at Christie Pits. As the game concluded, antisemitic provocateurs unfurled a homemade swastika banner to chants of “Heil Hitler.”

Jews battled members of the Swastika Club and other Anglo-Canadians for control of the swastika banner. The brawl soon escaped the confines of the ballpark and 10,000 participants and spectators filled the streets.

In the aftermath of the fighting, Toronto mayor William James Stewart declared his intention to prosecute future displays of the swastika. It was one of Canada’s first anti-hate speech policies—albeit an embryonic one.

This year, Canada celebrates 50 years of a federal multiculturalism policy. Immigration is no longer closed to non-white immigrants. Diversity is recognized as a strength by many. Racism, Islamophobia and antisemitism are condemned by the leaders of all of Canada’s major political parties.

But, despite these successes, important work remains to be done.

The swastika has again become ubiquitous across the country. Canadian Jews comprise 1 per cent of the population, yet are the targets of 17 percent of all police-reported hate crimes. Toronto’s Jewish community experienced a significant increase in hate-motivated crimes and remained the most victimized group in 2020.

The correlation between culture and hatred is as strong today as it was during the Christie Pits Riot. Antisemitism has moved beyond the newspapers and speeches of the 1930s. It now flourishes online with real-world consequences.

The riot exposed untenable social conditions that demanded change. Today there is no need to wait for eruptions of racial violence to work towards a more tolerant, just, and egalitarian Canada.

In this spirit, Canada must move beyond a simple championing of the idea of multiculturalism to a direct reckoning with specific histories. What happened at Christie Pits should be common knowledge, not a footnote in a history textbook.

To this end, I recently wrote a short documentary on the subject. Released as part of Historica Canada’s Multiculturalism Education Campaign, the video aimed at high school students has received over 100,000 views.

Soon after the video’s release, the comment sections (now disabled) were filled with antisemitic racism. Vitriol too malicious to be quoted ranged from blaming the Jews for their own persecution to accusing them of fabricating events as part of a conspiracy to colonize Palestine. This palpable digital hatred speaks to the continued importance of teaching tolerance in an accessible, dynamic way.

This work should not be the responsibility of the Jewish community alone. After all, Jewish-Canadian history is Canadian history, too, Antisemitism is a lived experience with an irrefutable past. As Jews, we have a responsibility to learn about and decry the injustices experienced by other racialized groups. We have a right to expect the same pursuit of justice from our allies.

Those outside the community have an obligation to grapple with Jewish history. In turn, we have the obligation to continue to tell our story, creating resources so all can learn from our past. Thankfully, these lessons are not without hope.

During the Christie Pits Riot, the Jews didn’t fight alone. They were joined by other immigrants who experienced discrimination. I’m confident that now, as then, the shocking rise in antisemitic racism will be confronted by both the Jewish people and their allies.

And I’m hopeful that it can now take place in the classroom—instead of on the streets.

Jamie Michaels is a Winnipeg-based writer and the creative director of Dirty Water Comics. He is a SSHRC Doctoral Fellow and Killam Laureate at the University of Calgary where he researches Israeli-Palestinian relations.

HEAR MORE: Canada’s worst race riot was 88 years ago today