On June 19, 1948, Mania Zaidman sat aboard the SS Marine Shark, a stodgy U.S. military vessel that chugged across the Atlantic from Hamburg to Halifax. The trip had taken two weeks; Zaidman was glad to be done with it. With stops in Belgium, France and the United Kingdom, the cargo ship plowed through the choppy English Channel, giving Zaidman, like so many others in her situation, an acute case of sea sickness.

She made the journey alone. The youngest of seven siblings, she survived the Holocaust in a Czechoslovakian Gross-Rosen camp, separated from most of her family. Many of them died, including her parents.

Zaidman spent two years in postwar Germany, learning English and working, before hearing about a Canadian program looking to bring over Jewish children who lost their parents in the war. There was just one catch: the orphans had to be under 18.

Zaidman’s 18th birthday was coming up fast, but when she asked about applying, an official told her not to worry – they could overlook her age and bring her in quickly. When she met with the Canadian ambassador in Germany, he assured her she’d “have a good life” in Canada.

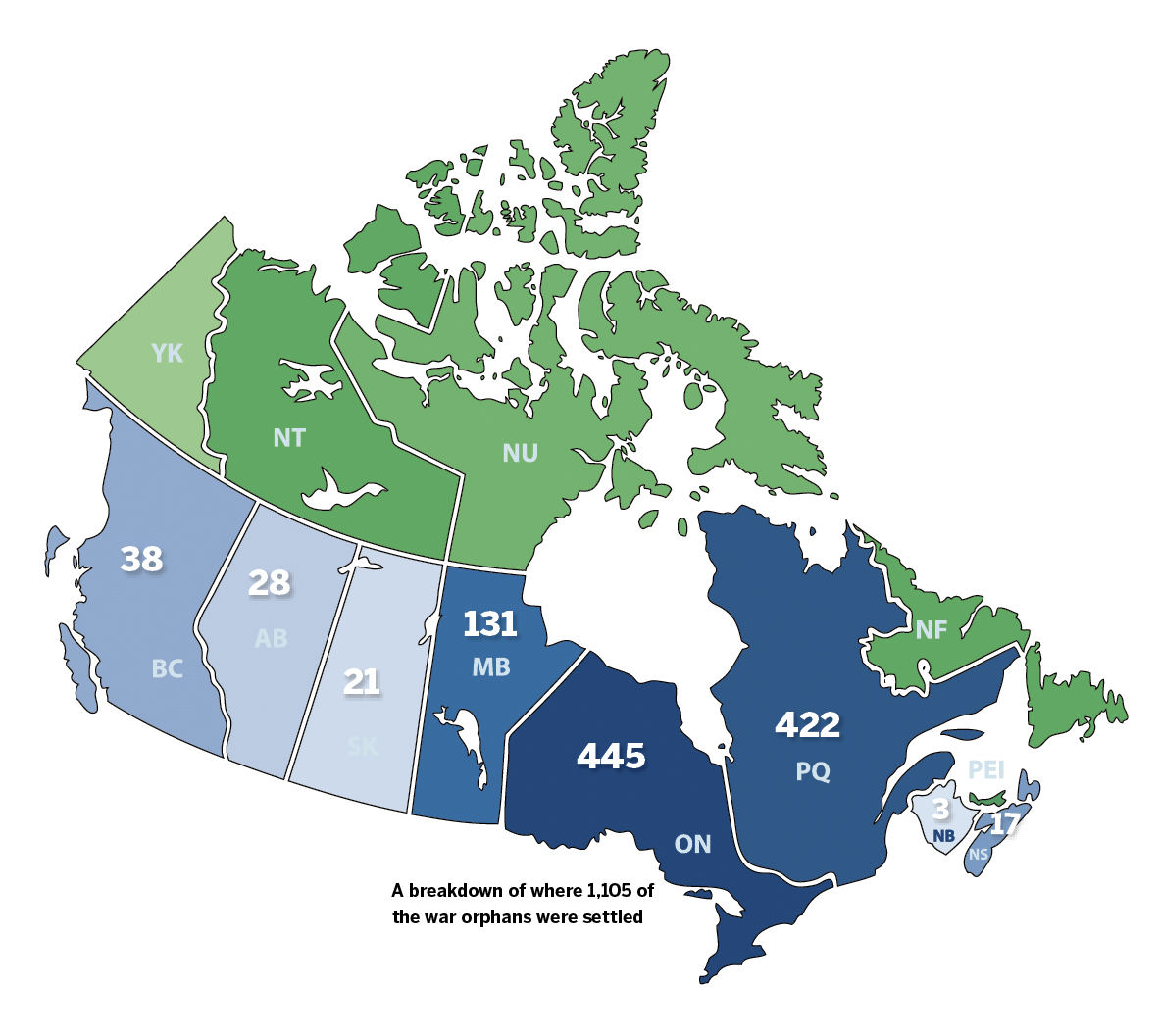

Zaidman didn’t know it, but there was a reason Jewish officials were eager to usher her into Canada. She was one of 1,123 eastern European war orphans brought over by a nationwide assembly of Canadian Jews, in spite of a largely xenophobic and anti-Semitic government. She was just one part of a sprawling, disorganized endeavour that saw traumatized refugee kids sprinkled across strangers’ homes from Port Alberni, B.C., to Glace Bay, N.S.

They called it the War Orphans Project.

When Zaidman stepped off the ship onto the salty, wind-whipped docks of Pier 21, she was brought to the home of a family who put her up for the weekend, fed her and gave her new clothes from their dress shop. On her first Sunday morning in Canada, they handed her $2 and a couple of magazines, wished her well and sent her off to Toronto, where she’d start a new life.

* * *

The idea for a Canadian War Orphans Project began in 1942, when the Canadian Jewish Congress (CJC) lobbied the federal government to bring over Jewish children whose parents had been killed in the Holocaust. Canada’s immigration department, under the purview of the openly anti-Semitic Frederick Blair and Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, reluctantly agreed to permit 1,000 war orphans into the country. But by the time the government accepted the paperwork, the Nazis had sealed off Vichy, France, where the Canadians had planned to find the children. As Ben Lappin wrote in The Redeemed Children, a 1962 study of the War Orphans Project, “What happened to this group will never be known.”

After the war, national attitudes towards immigration started to change. Canadians found themselves with a suddenly booming economy, resulting in a labour shortage that convinced the government to accept more “undesirable” eastern and southern European refugees, despite a majority of citizens still staunchly opposed to their migration.

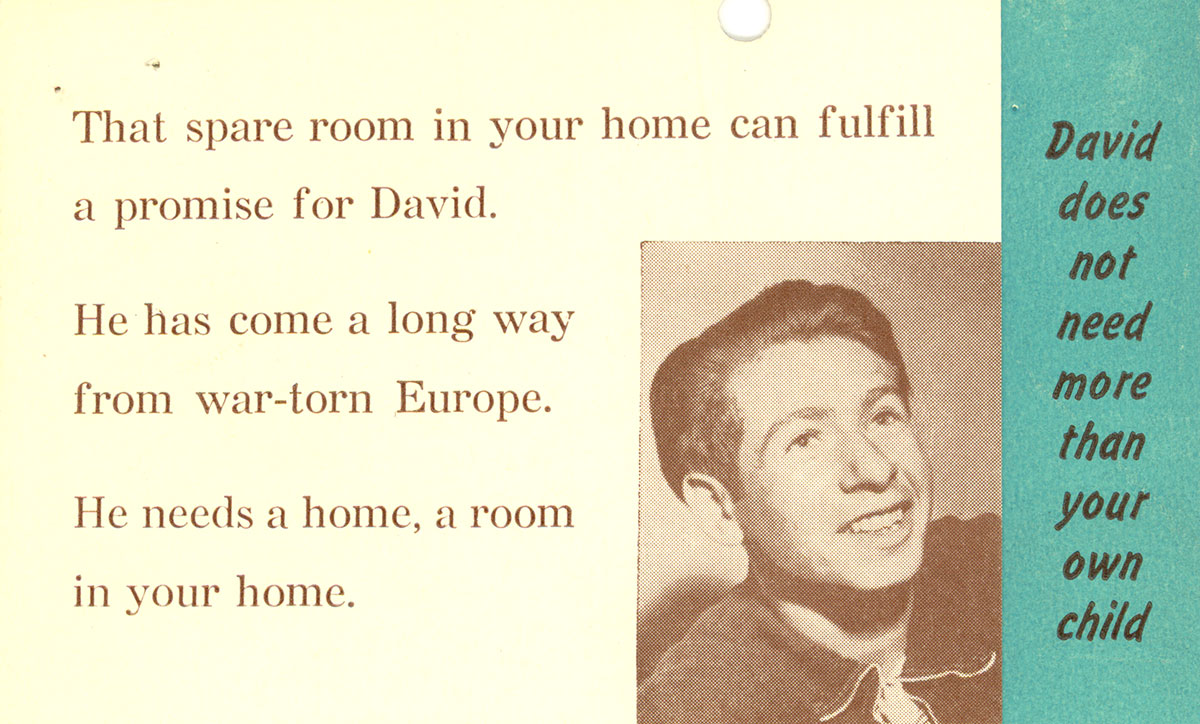

The CJC saw this as an opportunity. Once the approval to bring in the 1,000 Jewish orphans was renewed in 1947, it had three months to come up with a plan. It convened committees in Winnipeg, Montreal and Toronto, rounded up well-connected local volunteers, fundraised like mad and pleaded for Jewish families to open their homes and take in these displaced persons (DPs).

“If you are able to provide a home for one of these boys or girls, please notify the Canadian Jewish Congress of that right away,” implored a Jewish Radio Hour broadcast in April 1948.

The emphasis was not on charity, but on bolstering the Canadian Jewish community. “Giving a DP a potato a day may keep him alive, but it certainly won’t turn him into a useful citizen,” continued the broadcast.

READ: EXHIBIT ON FATEFUL ST. LOUIS VOYAGE ON AT WAR MUSEUM

In the spring of 1947, the CJC sent three scouts to Europe to find the 1,000 orphans. They assumed this would be an easy task, but they were wrong – one after the next, the locals shook their heads, explaining that, at most, they would find 150 viable candidates.

There were a number of reasons for this: Zionist agencies insisted on only sending children to Palestine; struggling governments refused to grant their surviving youth exit permits; communists wouldn’t let children become capitalists; and Christian foster parents wanted to keep children they’d grown to love. And then there was the simple fact that most Jewish children had not survived the war.

So while most Canadian Jewish foster families had requested pre-adolescent girls, it soon became apparent that they’d be getting teenage boys. Of the 1,123 orphans eventually brought over, 949 were 15 or older, and 70 per cent were male.

It makes sense, then, that a Canadian scout would be eager to bring over as many girls as he could find, even if it meant nudging back their dates of birth, as happened in Zaidman’s case.

The CJC tried to convince the Canadian government to raise the age to 21, but federal bureaucrats wouldn’t budge. “The basis for the scheme was to save children,” an official wrote in a memo in January 1948, “and I therefore think that extending the age limit to twenty-one is going beyond what was intended.”

Instead, many orphans simply forged their documents.

Instead, many orphans simply forged their documents.

Arthur Schwartz was 24 when he overheard some men on a Budapest street corner talking about the Canadian project. Schwartz had survived Auschwitz, only to find himself in a hospital for weeks. After that, he was robbed of his clothes in a public bathhouse, beaten up by anti-Semitic police officers, drafted into the Czechoslovakian army and pushed to make a living selling black-market cigarettes. Having just received his second draft notice, he knew he had to leave Europe.

Schwartz ran to his brother-in-law, a printer who happened to have identification papers from a dead 17-year-old boy named Samuel Weisberg. They printed up corroborating fake documents that Schwartz used to contact the Canadians and by March 1948, he was sitting in the immigration office at Pier 21. In the waiting room, officials called out for Samuel Weisberg several times before he remembered that was him.

* * *

While 2018 marks the 70th anniversary of the arrival of most of the orphans, the project ran from 1947 to 1949, with the last recorded orphans straggling through Pier 21 in 1952. Scouts in Europe found teenagers wherever they could, sending them in small groups on any vessel that would deliver them, often military or cargo ships.

George Reinitz came on the MS Sobieski in September 1948, with a small box of personal belongings he’d brought from Hungary. But, as he wrote in his memoir, Wrestling with Life, “I made the decision to start my new life in Canada with nothing from my old life in Europe. I threw my belongings overboard and arrived with nothing in my pockets but my hands.”

Reinitz was taken straight from Halifax to a reception centre on the second floor of the Herzl Hospital and Dispensary in Montreal, where many orphans stayed for days or weeks awaiting placement. Like the reception centre in Toronto, it quickly evolved into a bustling hot spot, filled with curious Canadians peeking in and asking questions of the newcomers – particularly, according to Lappin, girls who came “to flirt and look over the new boys in town.”

In smaller communities, orphans got placed in Jewish homes immediately.

On a freezing mid-February morning in Regina, local community leaders took Celina Kolin, 17, and her fellow refugees out for breakfast on their first day, before introducing them to their foster parents. “I remember our surprise at being served half-grapefruits,” Kolin recalled in a Pier 21 museum interview. “None of us had ever seen grapefruits before. We didn’t know what to do with them.”

Many orphans took to Canada with eager relief, often ending up in the garment industry. Zaidman found work sorting dresses in Toronto, while Schwartz earned $27.30 a week as a leather worker. Others became furriers, tailors and upholsterers.

By 1950, 70 per cent of the orphans had successfully integrated into Canadian society, according to an article written by Rabbi Abraham Feinberg in Canadian Welfare. But there were some problems: many non-Jewish Canadians were still opposed to the immigrants, and within the Canadian Jewish community, some feared these traumatized children would be mentally unstable.

“We were told we were damaged goods,” recalls Mariette Doduck, who settled in Vancouver at age 11. “We would become insane. We would live off the government. We couldn’t be good citizens.”

The CJC did not have formal social services in place, which, according to Rabbi Feinberg’s article, sometimes “bred introverted resentment on one side, and the self-righteous charge of ingratitude on the other.” Some parents wrote to the CJC requesting their foster children be resettled elsewhere.

Reinitz describes this feeling candidly in his memoir: “It was a hard lesson to learn, that no one really cared about the events that had so ravaged my entire family,” he wrote.

“There were times when feelings of sadness and anger so overpowered me that I felt like taking a baseball bat and beating the stuffing out of anyone who got in my way.”

The day after being introduced to grapefruit, Kolin was shocked by her foster family’s strictness. They forced her to burn her favourite red dress, which she brought from Europe, and demanded that she straighten her curly hair against her will. “Strange as it may sound, I wished I was back in the war, because then I was treated as someone who had rights and feelings by the people who had sheltered me,” she told the author of Open Your Heart: The Story of The Jewish War Orphans in Canada.

But the CJC anticipated emotional hiccups and organizers were always prepared to help. Kolin ran away to the CJC’s offices in downtown Regina and found comfort in the office of an organizer who let her sleep on a cot while they searched for another family.

Others were much more fortunate. After disembarking the train at Vancouver’s Waterfront station, Doduck was spotted by a Jewish man who’d been married for 30 years and couldn’t bear children. Doduck captured his heart immediately. He walked up to her escort and proclaimed, “I want that little girl.” Doduck lived with him and his wife for nearly eight years, raised children who called them grandpa and grandma and loved them dearly for the remainder of their lives.

* * *

The war orphans were part of the single largest influx of Jews to Canada since 1914, at a cost, according to Lappin, of nearly $1.2 million – more than $10 million today. The Jewish community raised most of the money itself, with barely any government help, to pay for reception centres, financial assistance, food, boarding, clothing, transport, staffing, rent, hospitalization, psychiatry, social workers, recreation and education.

The investment paid off: Sam and Gitta Ganz founded the multimillion-dollar Ganz toy company; Leslie Dan created the pharmaceutical giant Novopharm, becoming a billionaire philanthropist and recipient of the Order of Canada; Reinitz became a professional wrestler who represented Canada at numerous international events and was immortalized by the Reinitz Wrestling Centre in Montreal; filmmaker Jack Kuper directed acclaimed independent movies; Joseph Rothbart spent 51 years as the executive director of Montreal’s Mount Sinai Hospital; John Freund penned numerous memoirs; and Doduck co-founded the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre and was elected the first female president of Congregation Beth Israel.

READ: A MURDER OF JEWS WILL BE ACKNOWLEDGED IN NEW PLAQUE ON HOLOCAUST MONUMENT

And earlier this month, almost 70 years from the day she stepped off the SS Marine Shark, Zaidman – who now goes by Miriam Justein – sat in a packed room in the Drake Hotel in downtown Toronto, dressed in an elegant blue gown, to witness the wedding of her oldest grandchild, Ariel.

Ask just about any of Canada’s war orphans what they consider to be their greatest accomplishment and their first answer will not be their material victories, but their personal ones. Family is the truest form of survival.

Sitting in the front row, Justein watched the wedding officiant hand Ariel a cup of wine. It was the Kiddush cup Justein had purchased from an Israeli silver shop decades ago and brought out every Passover since. Last year, she gave it to her daughter. Now it was Ariel’s turn. Under the huppah, as the cantor sang, Ariel raised the auspicious cup to her lips and sipped the wine, as a blessing for their future.