I will know the novel coronavirus era is over when there is no longer a mask in my coat pocket. It exits that pocket less than it once did. It now saves its appearances for such situations as, I have a cold but still need to do things out in the world (as everyone does, though we briefly pretended isolating for two weeks at the sign of a sniffle was sustainable), or, I’m in a doctor’s office and would rather the higher-tech version than the blue surgical mask provided, lest a lab leak or pangolin have set forth the latest variant in a Toronto family doctor’s waiting room of all places.

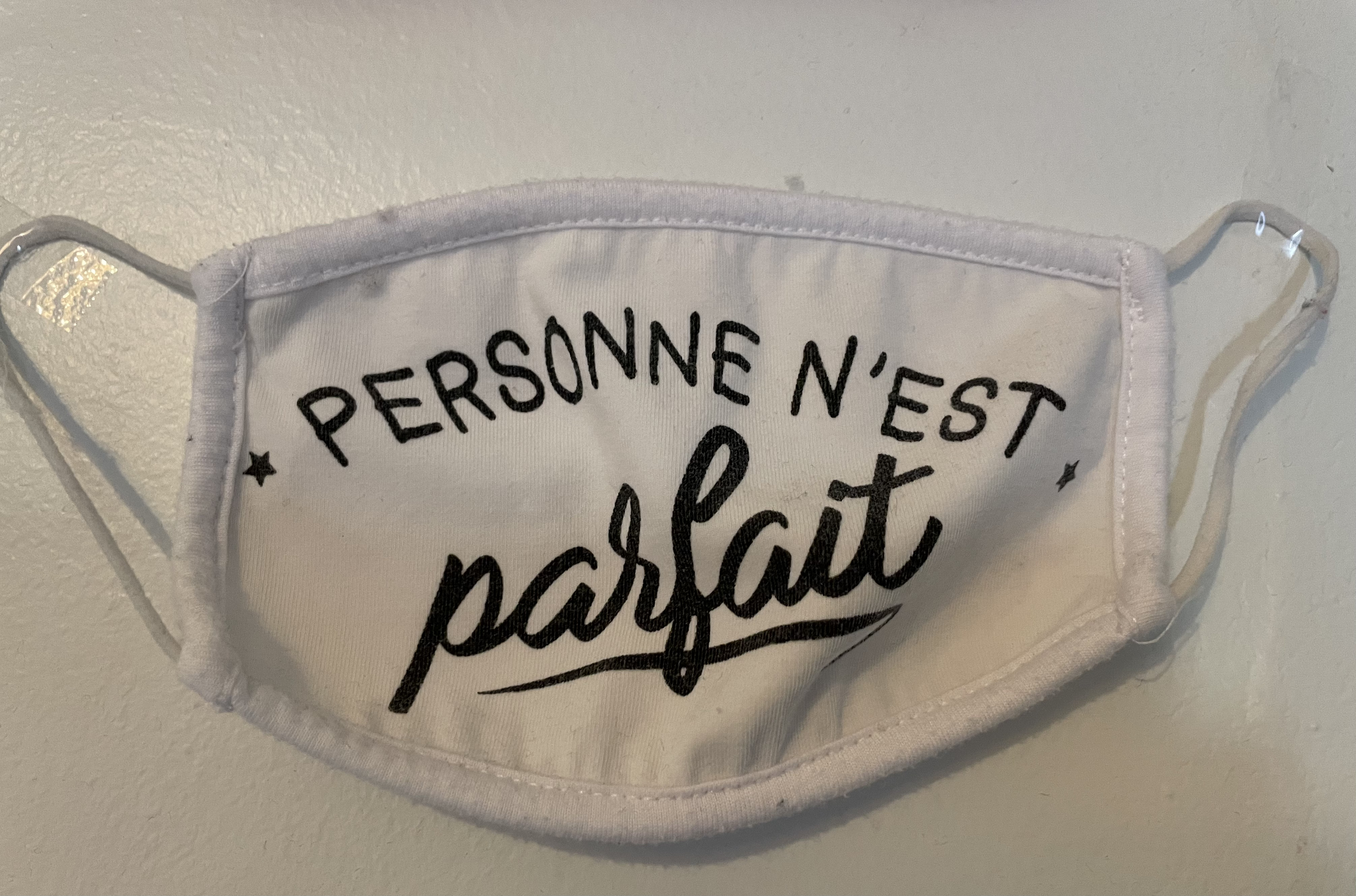

The big-picture impact of COVID is both obvious and confusing. One can talk around it but there’s no point: Death. On an unfathomable scale. Death, and fear. When the virus was new, when there were no vaccines, and when no one knew how it was transmitted, we were living in times more frightening than we may remember. Yes, three years ago isn’t all that distant, but there have been so many micro-eras since that it can be a bit of a blur. There were handmade masks, fitted from household objects (handkerchiefs, coffee filters), the cloth ones from Etsy, the doubled-up medical masks, and so forth. There were stockpiled N-95s, gathering dust, then whipped back out again as a new wave appears.

Then there’s the lingering impact of non-COVID problems, problems that are no less real and sometimes plenty fatal as well. I’m thinking, in part, of all the diseases not diagnosed or treated because you couldn’t (and sometimes still can’t) just go to the doctor as was once the case. In-person appointments all but disappeared, as did the phenomenon of accompanying a loved one to the hospital. So you have at once a situation where there’s this terrible new virus making things worse than ever for the immunocompromised, and on the other, all the ailments that predated this one getting worse, or getting trivialized. All of this happening at once.

But I’m also thinking of the wider societal impacts of lockdowns, of the children not allowed to interact in person at crucial developmental times, and of the young adults who found themselves in indefinite enforced isolation at ages when you’re supposed to be going out in a big group and finding that special someone or the special-enough someones.

Do we need to call this a youth mental health crisis for it to matter? I mean, I don’t doubt there is one, but it’s as much existential as it is medical. What does it mean to come of age in a world where merely being in a room with another person is so fraught? What would normal or healthy behaviour even look like?

I am, yes, thinking of the children, but how could you not? I can’t forget the school closures, even though my own family avoided these because our kids were too young/not born yet. I remember the forlorn looks on the neighbourhood kids’ faces as they brought home art projects and schoolwork in anticipation of yet another indefinite period of virtual schooling. I also remember the charming people posting online about how if you didn’t want to be locked in a house 24/7 with your children, supervising them and shepherding them through online school while holding down a job (if you indeed still had a job) then maybe you shouldn’t have had them.

The temptation at a three-year anniversary like this is to do some sort of retrospective. What have we learned? (Apart from how extremely important it is to be able to sit inside a coffee shop, indoors, and eat a croissant.) But we are neither in an after nor still, exactly, in the during. COVID, like HIV before it, has not only killed, but changed how we live.

The CJN’s senior editor Phoebe Maltz Bovy can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter @bovymaltz