For Wilf Gutzin, the dedication of a plaque in Toronto next week might prove bittersweet. It will finally mark a little-known chapter in the city’s Jewish history, but will undoubtedly churn up dark memories.

It was in the early afternoon of Jan. 20, 1950 when a fire broke out at the Phillips Garment Company, located at 447 Richmond St. W. In a basement, 10 workers toiled making coats and suits for women and young people.

The late Canadian Jewish historian Gerald Tulchinsky took up the thread, as it were, in an academic journal a few years ago:

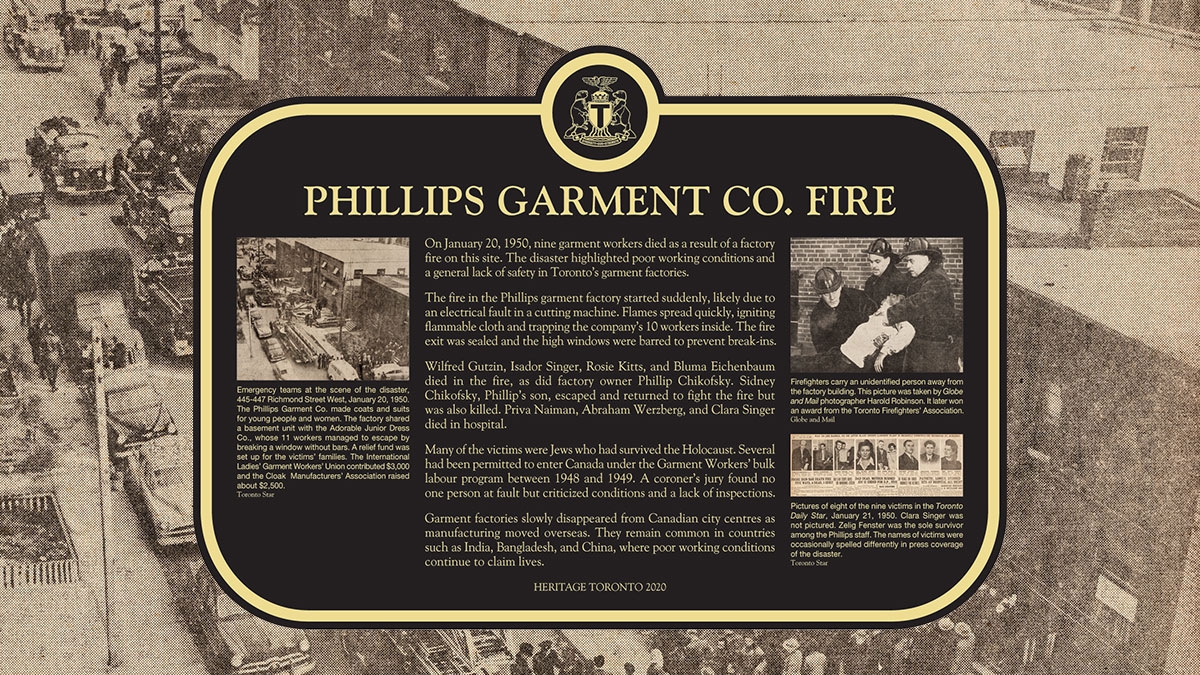

“The blaze started as a result of a short-circuit in a cloth-cutting machine. The fire ignited the layers of highly flammable cloth and adjoining racks of finished suits, dresses, and other merchandise.”

Only two of factory owner Phillip Chikofsky’s workers, who included his 18-year-old son, Sidney, escaped through the entrance. The others succumbed to the flames while attempting to climb through a window, but it was securely barred. “The two back-door emergency exits were blocked by a plywood partition and sealed shut by heavy iron bars, large draw bolts, and padlocks,” Tulchinsky recounted.

“Of the nine workers who perished, six died screaming and clawing frantically at the barred window: Phillip Chikofsky, his son Sidney (who, after escaping, returned with a fire extinguisher, losing his life trying to save others), Wilfred Gutzin, Isador Singer, Rosa Annie Kitts, and Bluma Eichenbaum. Three others—Priva Naiman, Abraham Weizberg, and Clara Singer—died in hospital a few days later.”

Zelig Fenster was the sole survivor.

Isador and Clara Singer, a married couple, left behind a four-year-old orphaned daughter, Ann.

Wilfred Gutzin—Wilf Gutzin’s grandfather—had four boys, just five years apart: Zelig, Harold, David, and Larry.

“I always knew about this because of how impactful it was,” Wilf Gutzin, a 53-year-old Toronto lawyer, told The CJN. His father, Zelig, was just 12 when his own father died in the blaze.

“It was within months of his bar mitzvah that he lost his father,” said Wilf. “Growing up, (the fire) was always known to me. My father would talk about the fact that he didn’t have a father during those years. My father showed me how to shave. He said his father wasn’t there to show him how to shave.”

Zelig Gutzin, a retired teacher who’s now 84, has memories of being photographed for newspapers, said his son. The fire had made all the front pages.

“He remembered being very confused about learning about this and also having to pose for a photo for the newspaper,” said Wilf.

Wilfred Gutzin’s widow never re-married and the fatherless clan survived through income from Workmen’s Compensation, as it was then known, donations, and renting out a store they owned on St. Clair Avenue.

Wilf’s father and an uncle, David, are Wilfred Gutzin’s surviving sons. Between their health concerns and COVID, it’s not yet known whether they will attend the plaque’s dedication.

According to the City of Toronto, many of the fire’s victims were Jews who had survived the Holocaust. Several had been permitted to enter Canada under the Garment Workers’ bulk labour program in 1948 and 1949.

The obscure episode in Toronto Jewish history will finally be recognized and memorialized on Oct. 6, when the city erects a plaque that explains the tragedy and pays homage to the victims.

The process began when Toronto Ward 6 Councillor James Pasternak was approached by David Gazit (Gutzin), Wilfred Gutzin’s other surviving son. Armed with old newspaper clippings, he told the horrible story.

“I didn’t know about it,” Pasternak conceded to The CJN. Gazit wanted to know whether the city could erect a memorial.

Pasternak got in touch with Heritage Toronto, a municipal agency dedicated to preserving the city’s history.

“They knew about it,” he recalled. “They knew about the nine workers who perished. And they were very enthusiastic about recognizing it.”

He then spoke to his council colleague, Joe Cressy, who represents the ward where the factory was located. “He was very supportive,” Pasternak said.

Funds to pay for the $7,500 marker were sourced under the Planning Act, and on June 29, 2020, city council passed a motion put forward by Cressy and Pasternak authorizing a memorial plaque to be installed at or near the location of the deadly blaze.

David Matlow, author of The CJN’s weekly feature “Treasure Trove,” which probes artifacts of historical significance, said he’s lived in Toronto for all his 60 years and had never heard of the Phillips Garment Company fire until the plaque initiative.

“From this story alone, we learn about Holocaust survivors who started their lives anew in Toronto (in) unsafe working conditions that led to their tragic deaths, and that this kind of work has now moved to other places,” Matlow said in an interview.

He said he hopes the plaque “motivates us to care about the working conditions of those people in faraway lands who today make the products we enjoy. History is not the sharing of interesting stories. It has a purpose: to make us more empathetic and inspired people.”

Said Pasternak of the deadly fire: “It was transformational in starting a really tough conversation about workplace safety.”

As the plaque notes, a coroner’s jury found no one person at fault for the fire at the Phillips Garment Co. but it criticized conditions and lack of inspections.

Tulchinsky, the combination historian-detective, took a customarily deeper dive that unearthed more than mere criticism.

Toronto’s then mayor, Hiram McCallum, ordered an inquiry into the tragedy and a survey of fire hazards in the garment district. The chief coroner for Ontario, Dr. Smirle Lawson, chaired the proceedings and described Chikofsky’s factory as “a death trap of the worst kind…it’s incredible to me that human beings should have to work in such a place.”

Although sealing off emergency exits violated municipal regulations, “police turned a blind eye to such closures, and representatives of three insurance companies admitted to refusing to accept risks in the garment district unless ground level windows and doors were sealed, to prevent theft, or unless burglar alarms were installed,” wrote Tulchinsky, who had interviewed Zelig Gutzin for his research.

At the inquiry, Joe (“J.B.”) Salsberg, the Labor-Progressive member of the Ontario legislature for St. Andrew and a veteran of Toronto’s garment sweatshops since 1916, “challenged the faulty machine theory. He indicated that the fire could have resulted from as yet unexamined factors and hinted at possible fault.

“While deeply regretting the tragedy, the (inquiry) found no fault and concluded that the deaths resulted from a flash fire ‘of unknown origin at a cutting bench, which ignited highly flammable celanese cloth.’”

The panel “also deplored the absence of proper, regular inspections and urged the city to establish systems of rigorous, routine inspections designed to avoid such tragedies in garment and similar small factories in the future,” Tulchinsky found.

A city council committee advised several measures, including that “all entrances and exits to factory buildings should remain unlocked and unobstructed during occupation of the premises.”

Toronto’s Jewish community responded “moderately” to the plight of families who had lost loved ones in the blaze. The Cloak Manufacturers’ Association raised some $2,500 for a relief fund, and the local branches and New York headquarters of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union contributed $3,000, according to Tulchinsky.

The Toronto fire serves as a reminder not only of the famous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 in New York, with its 146 deaths, mostly young immigrant women, “but also of the more destructive recent fires at factories in Bangladesh where, once again, workers perished behind locked doors,” Tulchinsky stated.

The plaque echoes the same sentiment—that while garment factories have slowly disappeared from Canadian city centres as manufacturing moved overseas, “they remain common in countries such as India, Bangladesh and China, where poor working conditions continue to claim lives.”

The memorial marks not only a painful event in Toronto’s history, but “one that is a double tragedy to the Jewish community, given that most of the victims were newly arrived Holocaust survivors,” noted Donna Bernardo-Ceriz, managing director of Ontario Jewish Archives.

The Phillips factory’s original location is now a vacant lot, so the dedication of the plaque will take place in Victoria Memorial Square, at Niagara and Portland streets, at noon, Oct. 6. The marker will be affixed later to a site closer to the original building.

Meantime, Pasternak is seeking as many descendants of victims as possible to come forward and attend the ceremony.

“We have received a few emails but we are on the hunt,” he said.

Remembering the Phillips garment fire, said Wilf Gutzin, will serve as a reminder not to take workplace health and safety for granted, even as factory fires elsewhere in the world continue to claim lives.

For him, the plaque will offer some closure.

“It means there’s actually a recognition that this happened,” he said. “Otherwise, it would be a forgotten chapter in history.”