Marc Raboy was easing into retirement in 2018 after a long academic career at McGill, when his partner suggested a trip to Argentina where she might practise her newly learned Spanish.

The South American country had always held a latent curiosity for Raboy as his paternal grandfather spent a year there in the early 20th century after emigrating from the Ukrainian village of Zhabokrych before later coming to Canada.

Raboy had known his grandfather, but never asked about his brief time in Argentina. Were other distant relatives still there? It simply was never discussed.

Before their trip, Raboy on a whim Googled “Raboy Argentina.” Raboy is an uncommon name, likely because it means “pockmarked” in Russian, and has several variations.

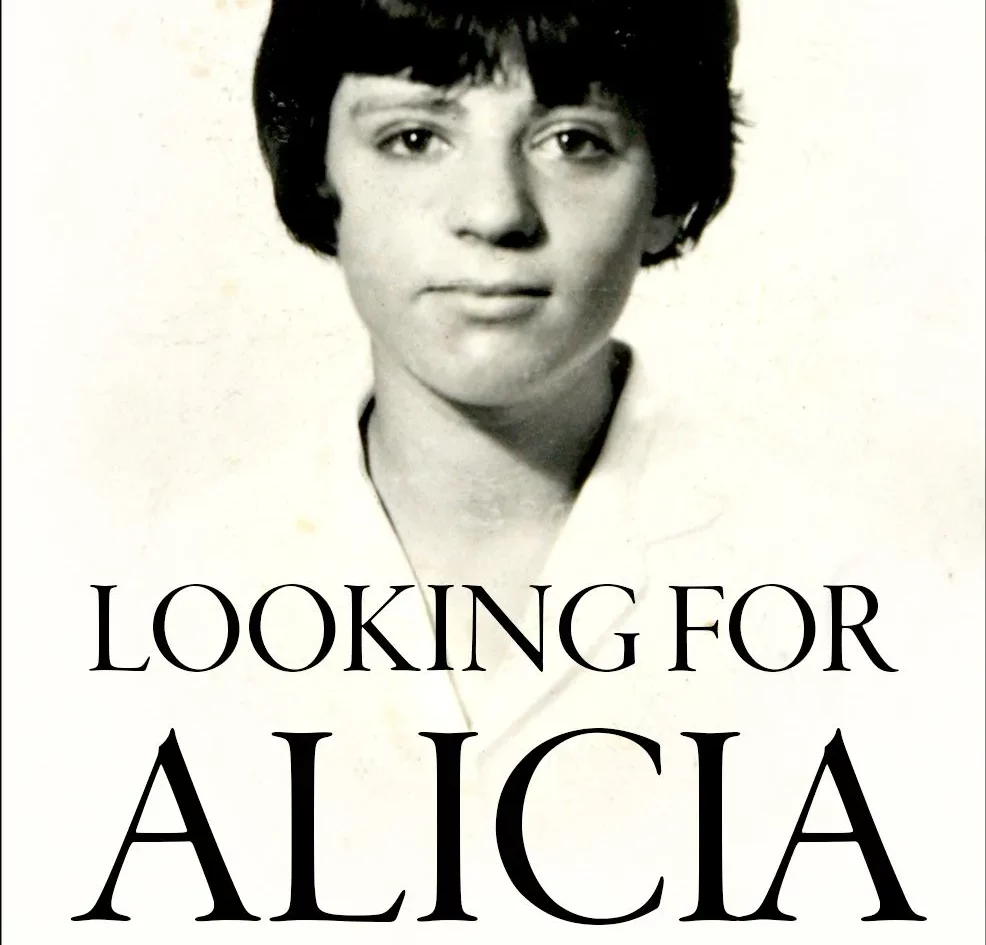

Raboy was astonished by what turned up: a young woman named Alicia Raboy was among the tens of thousands of resisters to the brutal military regime who “disappeared” in the 1970s in Argentina.

What had begun a pleasant vacation and a casual genealogical interest suddenly became the impetus for an in-depth investigation. The result is Raboy’s new book Looking For Alicia: The Unfinished Life of an Argentinian Rebel, published by House of Anansi Press in Canada and Oxford University Press internationally.

On June 17, 1976, Alicia, her partner Francisco “Paco” Urondo and their infant daughter Angela were ambushed by security forces in remote Mendoza.

Urondo, a well-known charismatic poet and journalist, was murdered in view of witnesses. Alicia and the 11-month-old child were taken to a detention centre. Urondo at least was accorded the dignity of having his body returned to his family and is remembered to this day as a heroic cultural figure.

The much younger Alicia became a “footnote to Paco’s story,” said Raboy. She was not seen or heard from again; her remains were never found and, in all the intervening years, no information has been uncovered. She is forgotten by all but her older brother Gabriel and Angela who, Raboy discovered, have not relented in their search for answers.

It can be assumed she was tortured unspeakably. Women and Jews were subjected to especially horrendous treatment, said Raboy, from a repressive regime which justified itself as defending “Western Christian civilization.”

Jews were disproportionately victimized. Although they represented about one percent of the population, 10-15 percent of the disappeared—a deliberate tactic to spread terror among the population—were Jewish, Raboy said.

To his mind, the crackdown was nothing less than a campaign of “extermination” of political dissidents. Highlighting Alicia’s story is Raboy’s way of putting a face to the up to 30,000 victims.

Besides sharing a name, Raboy was struck by other parallels between himself and Alicia. They were born within a month of each other in 1948, had four Jewish immigrant grandparents from the Russian empire, and were swept up in the politically turbulent 1960s.

“When I heard in the 1970s what was happening in Argentina, I wondered if I had been born there would I have been among the many young people fighting the dictatorship,” said Raboy.

Born into a middle-class family, Alicia had shown an independent spirit from an early age. While studying engineering at the University of Buenos Aires, she became involved in student politics.

Her resistance to the junta would not be limited to merely denouncing it. She joined the Montoneros, an armed urban guerrilla group that became the leading resistance movement, working as a journalist for its influential newspaper Noticias.

There is no evidence she took up arms herself; when she was abducted in Mendoza she was running a Montoneros daycare centre.

“I was struck by how similar our lives were up to a point, although mine, of course, was far less perilous,” said Raboy.

He began his working life as a journalist, first with the McGill Daily and then the Montreal Star. He gravitated to left-wing politics and community organizing. Unusual among anglophones, he sympathized with Quebec’s rising nationalist movement. After a sojourn in Europe, he tried his hand unsuccessfully in Montreal municipal politics.

Raboy then settled into academic life. He completed a 37-year career as Beaverbrook Professor Emeritus in McGill University’s department of art history and communications studies.

No stranger to biography, Raboy is the author of the 2016 Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World, an 870-page work that was a finalist for a Governor General’s Literary Award.

After Raboy’s initial 2018 visit to Argentina, he returned twice, spending a total of about five months there before the pandemic ended travel. He learned Spanish in the process and received valuable assistance from Stanley Diamond, president of the Montreal Jewish Genealogical Society, in his groundwork.

Alicia’s brother Gabriel Raboy and daughter Angela became close collaborators in the quest, which since the book’s publication carries on. Angela is one of only about 130 of the over 500 children of apprehended militants to have her identity restored after being adopted and her parents’ histories were erased.

In 2011, four by then elderly former police officers were convicted in the death of Urondo and the “illegal deprivation of liberty” of Alicia, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

“We keep hoping that someone will still come forward and say they remember her, that they were in the next cell to Alicia at the detention centre or that new DNA samples from mass graves being discovered will identify her remains,” Raboy said.

“For readers, I hope they take away, besides the particulars of Alicia’s story, a warning to be vigilant about what is going on today with the rise of right-wing populism. This is not a fairy tale from the past, but a caution that human rights, the rule of law, and respect for differences should not be taken for granted,” he said. “Let’s not underestimate the kind of evil out there.”

And are the Argentinian Raboys long-lost relatives? The reader will find out, but more important than blood kinship for Marc Raboy is the irreparable bond he has forged with them.