Look, it’s not like it’s the longest list in the world.

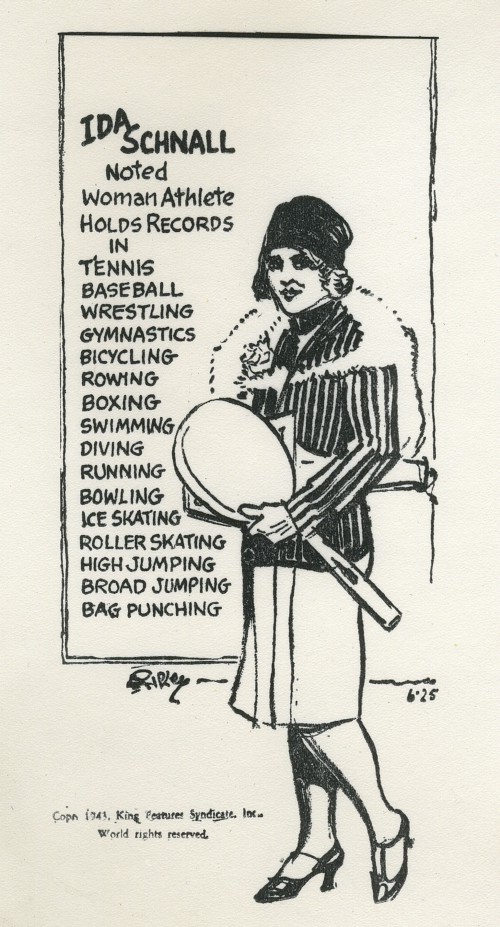

We can start with Sandy Koufax. Hank Greenberg. Mark Spitz. Bobbie Rosenfeld. Ida Schnall.

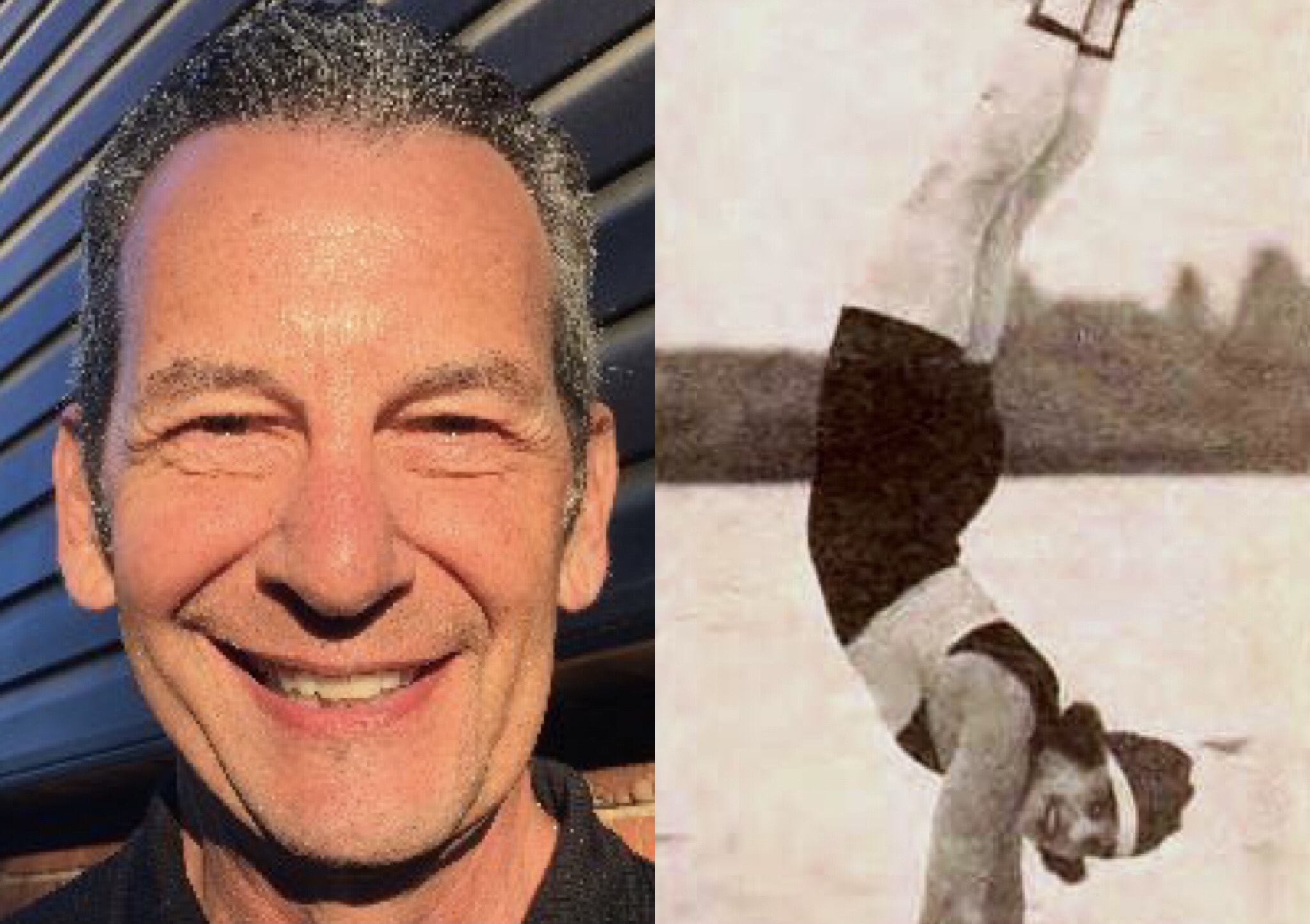

Wait… Ida who? Oh, you’ve never heard the story of Ida Schnall before? Well, you’re in for a treat over the next four weeks here at The Canadian Jewish News, as I outline why she’s the greatest Jewish athlete of all time.

While researching my 2019 book, The Greatest Athlete (You’ve Never Heard Of), I was trying to find a female equivalent of my subject, George Orton, who was Canada’s first Olympic champion and a multi-sport star. (Jim Thorpe would be the American equivalent overall.)

But it’s no surprise that there were very few female athletes of note in the early 20th century—and certainly none who were Jewish… or so I thought.

Then, I read a piece by Major League Baseball’s official historian John Thorn (who’s also Jewish) about Ida Schnall, and her incredible feats of athleticism.

She burst onto the scene, literally, in 1908, when she won the 100-yard dash and the 220-yard dash against Bronx high school girls, and then defeated the boys in the shot put.

At age 18, she organized the first female baseball team in New York, the Female Giants. They were a collection of mostly high school girls, half of whom were Jewish.

It’s believed that John McGraw, manager and part-owner of the New York Giants of the National League, wanted to introduce baseball to the thousands of Jewish immigrants who had flooded into the city. In fact, he had told his scouts to keep an eye out for any Jewish player who could help the Giants, knowing he would be a big box-office draw.

At the same time, McGraw wanted Jewish patrons to visit the Polo Grounds to see his Giants, instead of following the Highlanders (later the Yankees) or the Brooklyn Superbas (Iater the Dodgers). To that end, he encouraged Ida to promote and teach the game to young women. He even had his star pitcher, Christy Mathewson, teach Ida how to throw his famous “fadeaway” pitch.

Baseball was Ida’s first love, but diving is where she excelled. She was such a good diver, in fact, that she was expected to be the first American female to win a gold medal at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm. For the first time, women were officially allowed to compete for their country.

But then James E. Sullivan, secretary of the U.S. Olympic committee, and the most powerful man in amateur sport wouldn’t allow women to play for its teams, even though other countries were allowing their female athletes to.

Sullivan, who claimed to be a defender of modesty, said American women could only compete if they wore long bathing skirts, which covered their legs. Ida thought this was ridiculous, and called Sullivan out in the New York newspapers.

And so began a feud that lasted for the rest of Sullivan’s life. When he died a year later, under mysterious circumstances, the committee almost immediately changed the rules, and women were invited to register and compete in many sports.

Soon, swimming, diving and track and field clubs were established for women. It was Ida Schnall who led the fight for women’s rights on and off the athletic field. And she did so at the risk of her own career, taking on the establishment and demanding equality.

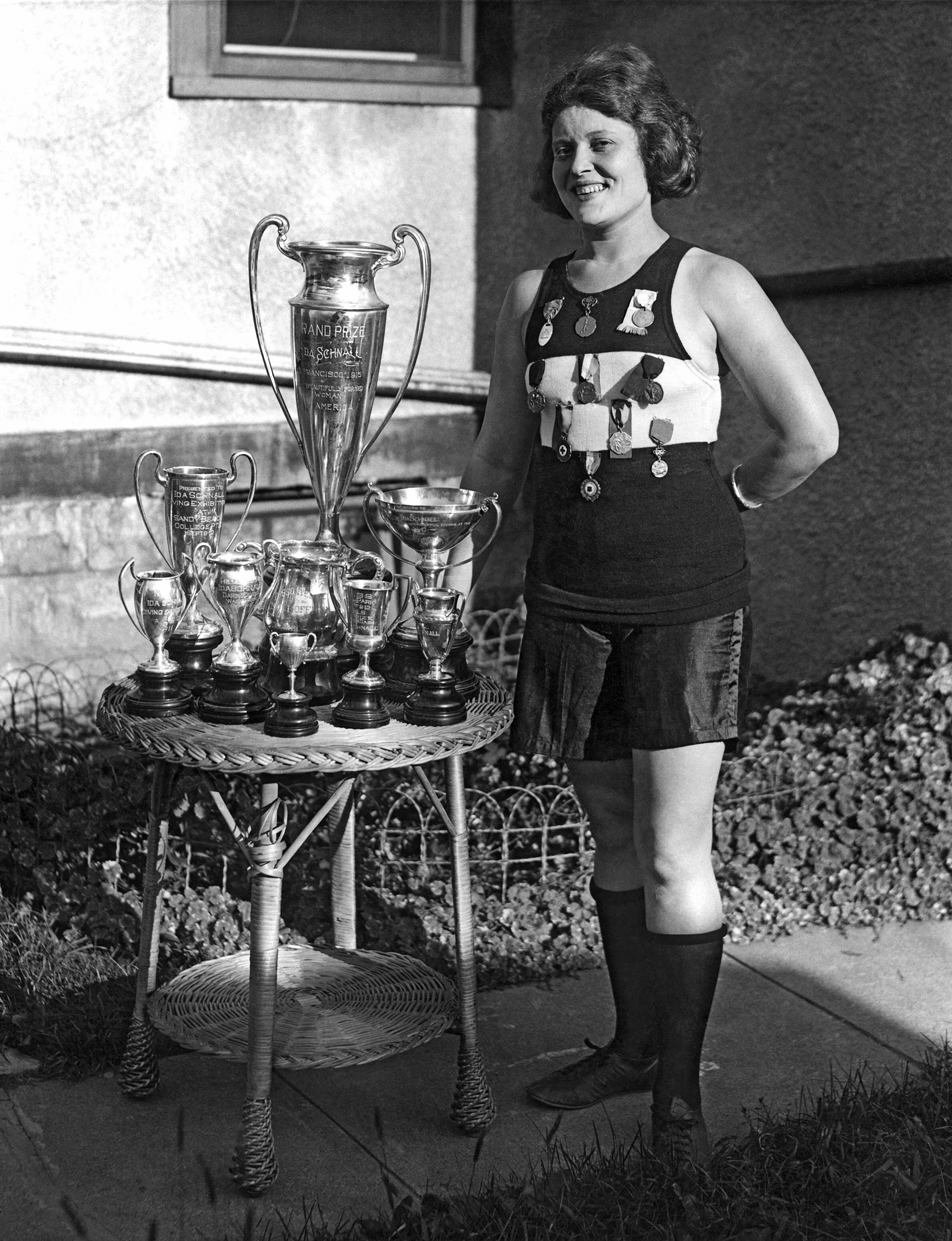

American women finally won the right to vote in 1920. They were also allowed, for the first time, to compete in the Olympics under the banner of the United States. By then, 31-year-old Ida was already a mother of two, and a star of stage and screen. And also a controversial figure.

Known as quite the daredevil, she had performed dives from the wing of an airplane, the top of the New York Stock Exchange building and a 135-foot dive into the Pacific Ocean for the movie Undine. She’d been arrested for indecent exposure by daring to wear a one piece bathing suit on a public beach at Coney Island.

Ida’s great-niece, Ellie Graf, told me a story of how, in 1945, Ida showed up at San Diego’s Mission Beach wearing only her slip and her underwear. “You should have seen the crowd around her. Ida was beautiful, with soft brown hair and a lovely figure, even in her mid-50s. She just loved the attention.”

Then there was the time when racy promotional photos of Ida, dressed as a mermaid in Undine prompted obscenity charges against a theatre owner in Kentucky. (He was found not guilty.)

Ida’s body was the topic of many discussions over the years. She toured with muscleman Charles Atlas for a time, and was awarded the title of the “Most Beautifully Formed Woman in America” at the 1915 San Francisco Exhibition.

She was invited to the White House to meet the president, William Howard Taft. She had her portrait painted by the legendary Howard Chandler Christy. She was a top-ranked amateur tennis player and an inspiration to Babe Zaharias-Didrickson, Gussie Moran and countless other female athletes.

Plus, she was a tireless promoter and advocate of women’s physical culture, and did more to raise the profile of women’s athletics until Billie Jean King came along a half-century later.