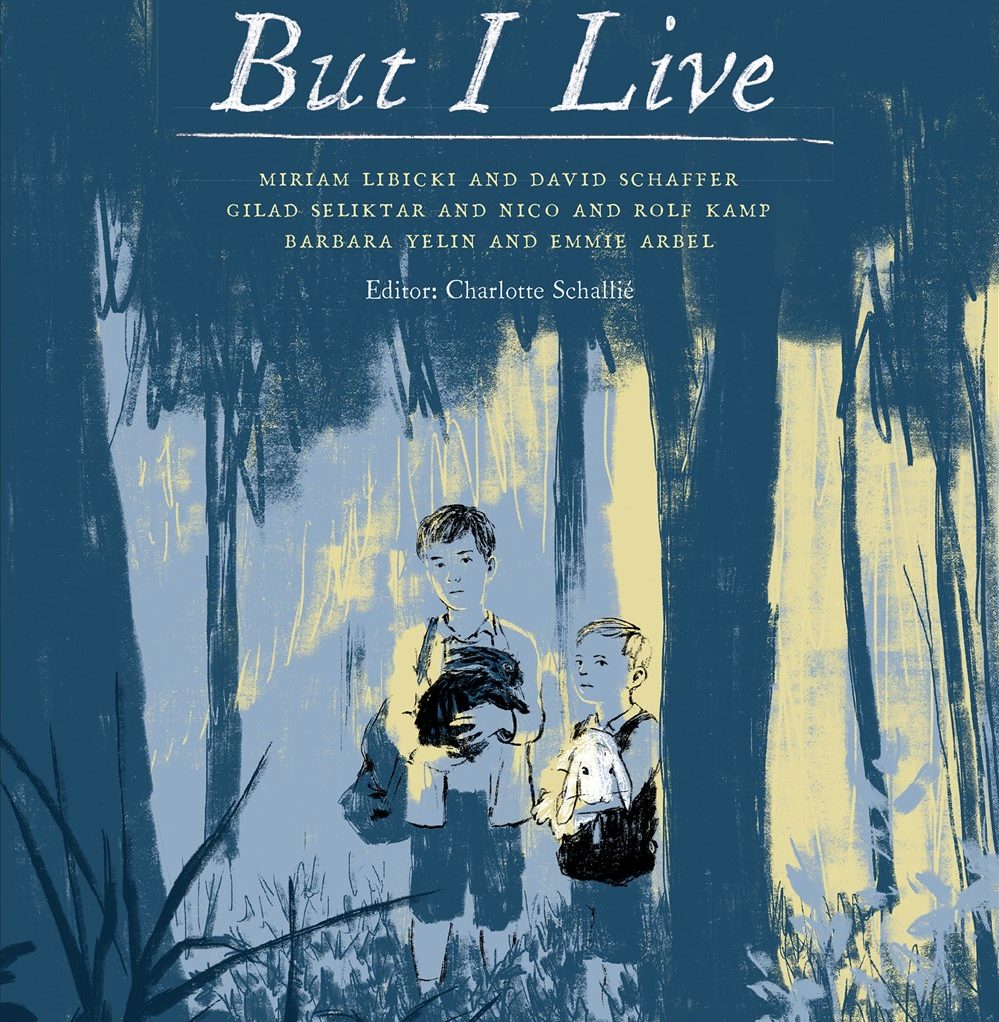

But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust, by Miriam Libicki and David Schaffer; Gilad Seliktar, Nico Kamp, and Rolk Kamp; Barbara Yelin and Emmie Arbel; edited by Charlotte Schallié

German philosopher Theodor Adorno famously said that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” The meaning of this statement has since been debated at length. Perhaps he meant that the barbarism of genocide had stripped words of beauty, and that the entire medium of poetry had to be entirely reinvented. Even if so, we can certainly still find meaning in art about the Holocaust, specifically in graphic narratives. These are powerful forms of storytelling where images can capture emotional depth where words would otherwise fail.

Graphic forms of testimonial storytelling have long been produced to depict the Holocaust. Take for instance Charlotte Salomon’s powerful Leben? Oder Theater?: Ein Singspiel (‘Life? Or Theatre?: A Song-play’, 1940–42), widely considered a proto-graphic novel.

Then there is The Survivors’ Haggadah (1946), which reimagines the Passover story with the experiences of survivors, and includes seven haunting woodcut images by Miklos Adler depicting the suffering of Jews in concentration camps.

And, of course, there is Maus (1980–91)—the only graphic novel to ever be awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

But I Live, published by New Jewish Press (an imprint of University of Toronto Press) stands as the inheritor to this long tradition. Its focus is three stories of child survivors.

The first, “A Kind of Resistance” by Miriam Libicki and David Schaffer, is Schaffer’s story of his and his family’s survival in hiding in Transnistria. The narrative begins in 1939, when he is eight years old. As the story unfolds, we see his character aging and slowly wasting from hunger. His eyes become larger and his face becomes gaunt, which is juxtaposed with depictions of present-day Schaffer recounting his experiences to his grandchildren. Through Schaffer’s words and Libicki’s artwork, his narrative comes to life in striking and vivid watercolour, giving an impression of the imperfect lines that surround memory. We reflect on the meaning of that loaded term “resistance,” and Schaffer’s own complex relationship with it.

In the second narrative, “Thirteen Secrets,” the story of Nico and Rolf Kamp’s 13 hiding places in the Netherlands during the Holocaust takes on a kind of cinematic quality through Gilad Seliktar’s blue-and-yellow sketches. They bring together the different perspectives and recollections of both brothers. As in the previous narrative, the brothers are reflecting as adults on their childhood experiences. In this novella, the illustrator himself is a character, speaking to the Kamps in their Amsterdam homes, and walking about the city together.

The final narrative is the title story “But I Live” of Emmie Arbel, who was only four when deported to Westerbork Transit Camp and then to Ravensbrück, and later to Bergen-Belsen. Now an older woman living in Israel, she shares her recollections—those which she retains, at least—with the story’s illustrator, Barbara Yelin. The lighter tones of Israel contrast sharply with the dark muddiness Yelin uses to depict the camps, suggesting the presence of death. Yet the darkness also seeps into Arbel’s present, where trauma leaves an indelible mark. Narrated with stark and honest statements, the story is punctuated by moments that Arbel cannot recall, with her constant refrain being “I don’t remember.”

But I Live is a thoughtfully crafted book that consciously grapples with the idea of voice and representation in the stories of Holocaust survivors, especially those of child survivors. The voices of survivors are treated with deep respect, and it is their stories that are highlighted rather than those of perpetrators or bystanders. It also provides a meaningful reflection on the experience of co-creation between a subject and artist, as each artist’s unique style is used to bring the survivors’ stories to life.

This volume is truly a collaborative effort. The stories are followed by insights by historians, the artists, and the survivors themselves on the historical context for each story, and on the process of developing the graphic narratives. It is also a deeply international effort, crossing borders and languages.

But I Live is a powerful demonstration of how to effectively and meaningfully engage audiences with Holocaust testimony. It makes a compelling argument for the use of graphic narratives as effective tools for teaching the Holocaust. Indeed, this is a book that not only everyone should read, but, given its focus on stories of child survivors, it is also certainly deserving of being taught in schools.

Last month, I wrote about the dangers of The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas and its sequel. But I Live is its narrative superior in every respect. It is emotionally affecting and a remarkable achievement that carefully considers the voices of survivors. With International Holocaust Remembrance Day upon us, it has the ability to strike a chord with readers and convey the important message: Never Again.