It’s a mystery nearly 110 years in in the making: Who murdered Winnipegger Sarah Feinstein? Finding an answer to that question occupied over a decade of Wayne Hoffman’s life.

Hoffman, the executive editor of Tablet and a resident of New York City, is the great-great-grandson of Feinstein, who was murdered in 1913. The killer was never found.

The story Hoffman’s mother told of the killing, and that she passed down to the family, was that Feinstein was shot by a sniper while sitting on her front porch. But was that the case? Hoffman decided to find out.

“I never believed it,” he said. “It didn’t make any sense.”

For years, he kept his skepticism from his mother. But when she was diagnosed with dementia in 2010, he decided it was time to record the stories of her life because she was the keeper of family memories, including her grandmother’s murder.

When Hoffman said he was skeptical about her sniper story—that it was “malarkey,” as he put it—his mother asked: “’If that’s not what happened, then what happened?’”

As a journalist, Hoffman thought it might take a few weeks to find out. “I thought it wouldn’t take long to set right,” he said.

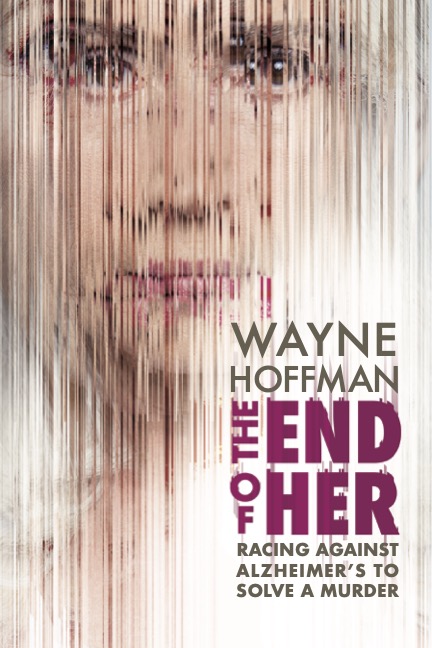

But a few weeks turned into a decade of research before it became the book The End of Her: Racing Against Alzheimer’s to Solve a Murder.

Along the way Hoffman made two visits to Winnipeg, in 2013 and 2017, and found 20 long-lost relatives in Canada and other countries. “I discovered a family history I never knew.”

On his first trip to Winnipeg, Hoffman came to see the places in the city’s north end where his family had lived. The second time, he came to visit relatives and hear their stories.

“At the time, I didn’t know it would be a book,” he said. “But things kept growing.”

Prior to those visits, he had never visited Winnipeg before, or thought about it at all.

“I went from never thinking about the city at all to thinking about it all the time for a decade.”

As for the mystery itself, Hoffman is “99.9 percent sure” who did it—but you have to buy the book to find out.

Beyond the murder itself, the book is also about Jewish life in Winnipeg at the turn of the last century. “It’s also a history of Jews in Winnipeg, and what it was like to be an immigrant in North America back then,” he said.

This includes the way newspapers and police regarded Jews. “Stereotypes about Jews were rampant,” he said, including how Jews were seen as “overly excitable, highly superstitious, and who shared rumours filled with nonsense.”

It’s within this context that the murder of his great-great-grandmother plays out in the book.

“My family story ties in with the story of Jewish life in Winnipeg back then,” he said, adding it shows how life as an immigrant was “much grittier” than the typical story of upward mobility and success of newcomers.

Unfortunately, by the time Hoffman completed his research, his mother’s dementia had developed to the point she could no longer communicate or understand what he was saying.

“I hoped to do it quickly for her, to answer the question,” he said. “I had no idea how long it would take.”

Hoffman is launching his book online, Feb. 20 at 1 p.m. CT. For more information and to register, visit the website of Winnipeg’s Jewish Heritage Centre of Western Canada at https://www.jhcwc.org/programs/