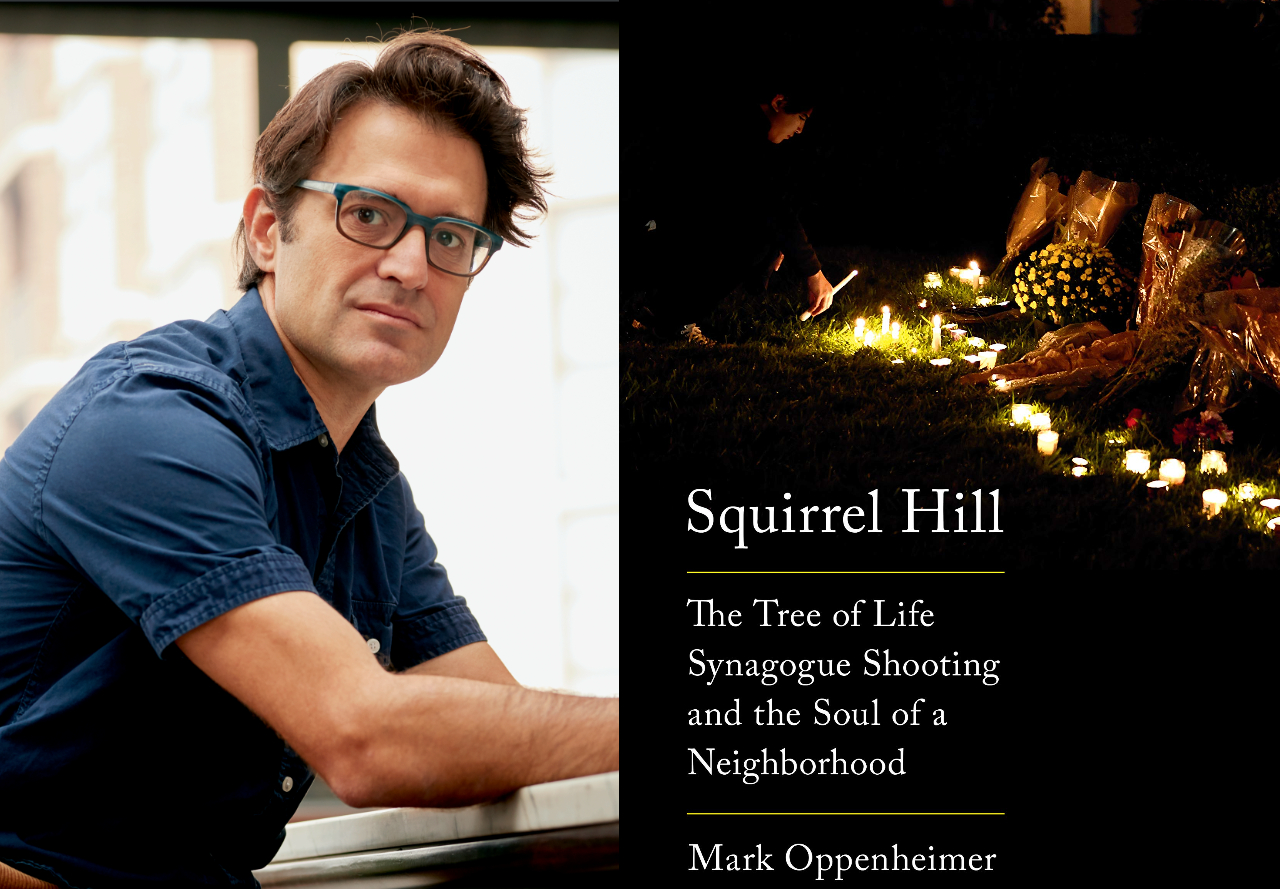

After the Oct. 27, 2018, mass killing at Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, when 11 members of three different congregations (all houses under one roof) were killed—the deadliest antisemitic attack in American history—I traveled to the Squirrel Hill neighborhood 32 times over the next year and a half to interview people about the effect of such an event on a community. Although the resulting book, Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood, contains many sad stories of loss and suffering, I also heard many quirky, unexpectedly funny tales. An event like the Tree of Life shooting has ripple effects that no one could have guessed. Here is one story from the book, about a Pittsburgher who found that the 11 deaths, of people he did not know, had far-reaching repercussions—on his wardrobe.

“I am usually unmarked,” Robert Zacharias said late one afternoon in December 2018. “Zach” had been mentioned in the press for attending a rally put on by IfNotNow, the left-wing Jewish group, and we were talking about Pittsburgh’s radical Jewish scene. As it turned out, Zach was not deeply involved politically—he was more of a curious seeker, in his politics and in his religion. “I’m usually just, like, some boring person—there’s really not much to comment on if I walk by or bike by or something. I’m just some dude. But if I’m wearing a yarmulke, I’m part of an identified special weird class. There’s something unique and unusual about me that makes me not merely some dude: potentially a person to commit violence against or be angry at, potentially somebody to be appreciative toward… somehow separated from the masses.”

Zach teaches at Carnegie Mellon—physical computing, the art and science of building novel interactive objects, “everything from a motion-activated cat toy to an automated yarn-ball winding machine to a device that helps people experience a dance performance through touch.” There is an astonishing normalcy to him, a true absence of danger, but it would be unfair to accept his self-description of “boring.” Rather, he is exceptionally likable. He is tall and lanky, blue-eyed, reddish-bearded, and soft-spoken. He is the summer camp counselor with a guitar who could really sell “Kumbaya.”

Zach was born in 1985 and grew up in Maplewood, New Jersey. His family belonged to a large Reform temple that they seldom attended. After college, he moved to “so-cool Greenpoint,” in Brooklyn. He worked at an education nonprofit, and he was in “a cool apartment, living the ostensible dream.” But it didn’t feel like a good fit. “It didn’t seem like I was actually enjoying it as much as I was supposed to be enjoying it on paper.”

As he tried to figure out who he was and where he wanted to be, he wandered into a semblance of Jewish community. In 2013 he went on a date with a Jewish woman who told him about some email lists that served unaffiliated, progressive Jews. He and the woman never went out again, but he got on those email lists, and he learned about some off-beat Jewish worship groups. He started occasionally attending services with Shir HaMaalot, which followed Friday-night Shabbat prayers with potluck dinners. (The dinners had three tables: one for vegan food, one for vegetarian, one for kosher.) At an event at Romemu, the Upper West Side community known for its spirited musical services, he met Amichai Lau-Lavie, the founder of yet a third community that intrigued him, Lab/Shul, which calls itself “an artist-driven, everybody-friendly, God-optional, pop-up, experimental community for sacred Jewish gatherings.”

Zach never became a regular with any of these groups, but they kindled an interest in Jewish religious life. When he left Brooklyn for Pittsburgh, he found overlapping Jewish communities including IfNotNow (whose politics he considered a bit too strident), a small, home-based branch of the Chabad movement (whose Orthodoxy was far from what he believes in), and Moishe House, a Jewish communal-living house for recent college graduates (whose typical hanger-on was, he admitted, much closer to college age than he is).

The morning of the shooting, Zach had been hanging with an IfNotNow friend at her apartment in Bloomfield, northwest of Squirrel Hill. After getting the news, Zach went home. He checked in with his family and friends, and a couple hours later, in midafternoon, he went to the Giant Eagle supermarket to buy soup and yahrzeit candles, small candles one lights to honor the dead. Before he left, he dug into his closet for one of his yarmulkes. He put it on and left for the market. That was the first time he had ever worn a yarmulke when it wasn’t Shabbat, a Jewish holiday, or some other special occasion.

Zach kept the yarmulke on his head at the Havdalah planned by the Allderdice students. He has been wearing one ever since.

“It is a new experience for me to be wearing a yarmulke out in the world on a regular basis,” Zach said. “It has these interesting implications.” He mentioned a night when he and his girlfriend had been trying to decide where to go out to eat. “I was like ‘Well, Gooski’s is open’—and then I was like, ‘But I heard they have some Nazis.’ ” Zach was referring to the rumor that, at some point, some sort of neo-Nazi punk band had played a gig at Gooski’s, a small dive bar in the Polish Hill neighborhood. Zach figured the rumor was probably false, but his head was spinning with possibility. He’d thought about the overlap between punks, many of whom lived in Polish Hill, and various strains of white nationalist ideology.

And then he realized that if there were neo-Nazis hanging out at Gooski’s, he now looked like a target. “But I didn’t want to take my yarmulke off to go to Gooski’s and have dinner. That doesn’t feel right.

That’s some kind of bizarre paying-of-obeisance to the ghost- or not-ghost-Nazis, and I don’t want to do that. But I also don’t want to not go to Gooski’s if I want to go to some neighborhood bar that has vegan kielbasa!”

The yarmulke complicated everything. If he took off the yarmulke, the neo-Nazis, real or imagined, would win. If he kept the yarmulke on but skipped Gooski’s, the neo-Nazis, real or imagined, would still win, by depriving him of tasty vegan kielbasa. But if he said yes to the yarmulke and to Gooski’s, he put his visibly Jewish self in sight of the real or imaginary neo-Nazis. (To be clear, there is no evidence that neo-Nazis hang out at Gooski’s.)

Zach weighed his options, screwed up his courage, and took himself and his girlfriend to Gooski’s. When he stepped inside, he took a look around, and his first thought was, These are not people who want to hurt me. They’re not antisemitic people here. He saw a coworker at the bar, reading The New York Times app on his iPhone as he drank a beer and smoked a cigarette. It was all copacetic.

But the yarmulke was not finished with him yet. He and his girlfriend sat at the bar and placed their orders. “I made a very expensive order by mistake… and I was like, ‘Oh, I shouldn’t get all that.’ ” He turned away from the bar to look at his menu, to figure out what to order instead. And as he turned away, he noticed the bartender noticing his yarmulke. And then he was immediately concerned that she would see his changing his order as a manifestation of his Jewishness. “I was like Oh Goddamnit. Now I’m a money-grubbing Jew! Like, I’m complaining about the expensive order and adjusting my order to be less expensive! So I felt bad about that, because now I’m a symbol of ‘all the Jews.’ I am the standard-bearer for all these people for whom I don’t bear a standard!”

Zach was still feeling like the guy in a yarmulke who had flagged a problem with his restaurant tab when something compounded his misery. He lifted his bottle of Yuengling to his mouth to have a sip, and a bit sloshed out and landed on a man sitting next to him at the bar. It was just a tiny bit of beer, and it seemed that the man didn’t notice. So Zach elected not to say anything. “I thought, Oh, he doesn’t notice, doesn’t matter.” But no sooner had Zach elected to let the matter drop than the man turned around—he had noticed. Zach quickly apologized, hoping to make everything right. But it was too late. “I was like, ‘I’m sorry, I spilled some beer,’ but I hadn’t said it when I spilled it. So yet again I think, like, Now I’m a jerk, a selfish, unapologetic Jew person. So it’s even worse! Everything is bad!” He threw his hands up in despair. A public Jew can never win.

Those moments of discomfort were not enough to get Zach to doff his yarmulke. It became part of his regular getup, and the times when he felt self-conscious or worried about his appearance became fewer. Still, there were occasions when it seemed prudent to cover up. One time he went for a walk in the woods outside Pittsburgh. “I am out in deer-hunting country,” he remembered thinking to himself. “I don’t know who the hell is here, but if I’m going to run into some backward, racist jerk in Pittsburgh, it’s going to be out in the woods where there’s deer-hunting permitted So I wore a hat over my yarmulke in case I ran into somebody.”

The only time he took his yarmulke off was when he went home to New Jersey for Thanksgiving, the month after the shooting. His parents had “always been leery” of Zach’s surging interest in Judaism—his month on a kibbutz in Israel, his frequenting various alternative Jewish spaces in Brooklyn and Manhattan. So somewhere along the Garden State Parkway, he took his yarmulke off. “I thought I’d get a lot of comments, and confusion I thought all my cousins would give me weird grief about it. I thought my parents would be confused by it. I thought they would all think I was signaling some virtue that I didn’t mean to be signaling, or that I was garnering pity, which I didn’t mean to be garnering”—pity as a Pittsburgh Jew, one month after Tree of Life. “Of all the things I could have been afraid of, like what random strangers were thinking in Pittsburgh, I was actually afraid of my family. And so I didn’t give them the opportunity to even worry along those lines. I took it off.”

Excerpted from Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood by Mark Oppenheimer. Copyright © 2021 by Mark Oppenheimer. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.