Prof. Alan Dershowitz of Harvard University is a scholar and activist that the Jewish community can be proud of. He has dedicated his life to the pursuit of human rights for Jews and others, while at the same time establishing an impressive record as a criminal lawyer. He is also a strong and effective defender of Israel on campuses and beyond.

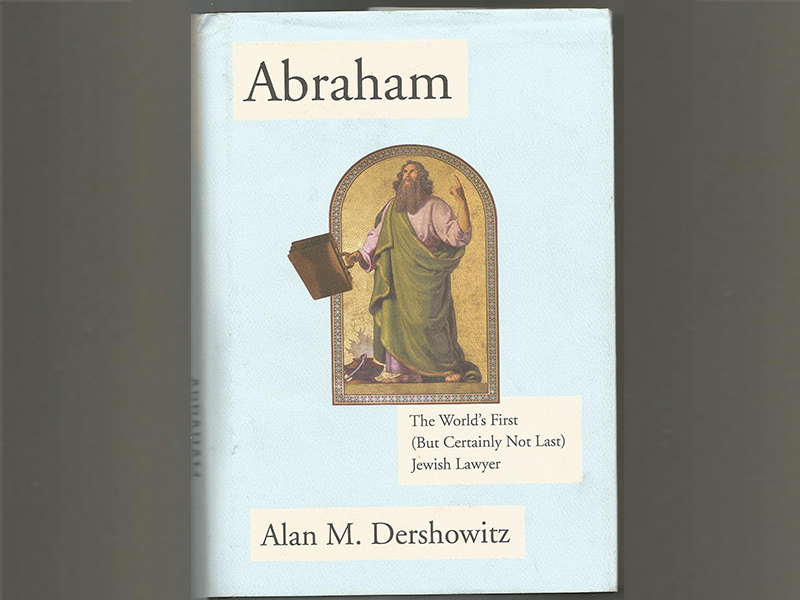

The author of over 30 books, Dershowitz’s latest offering is Abraham: The World’s First (but Certainly not Last) Jewish Lawyer. Dershowitz provides a unique analysis of the Abraham stories in the Bible, with frequent references to how they were understood in the Jewish tradition.

Two Bible stories about Abraham are central to the thesis of the book. For Dershowitz, Abraham’s speech to God about the impending destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah was his finest hour. Abraham challenged God, “Will You sweep away the innocent along with the guilty?” He spoke truth to power, demanding that God exercise justice and fairness: “Far be it from You to do such a thing, to bring death upon the innocent as well as the guilty, so that innocent and guilty fare alike. Far be it from You! Shall not the Judge of all the earth deal justly?” (Genesis 18:23, 25).

READ: AN IMAGINATIVE, MOVING PORTRAIT OF KING DAVID

Dershowitz feels that Abraham fell short in the story that appears a few chapters later in Genesis 22, when God commanded Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac. Abraham acquiesced too willingly, according to Dershowitz. He should have argued against God for giving him this patently immoral order. Instead he behaved like a religious fundamentalist, not a compliment in Dershowitz’s worldview.

Jewish, Muslim and Christian traditions consistently praise Abraham’s selfless behaviour and deep faith in God as demonstrated in the story, but Dershowitz’s atypical understanding underlies the rest of the book, his survey of Jewish lawyers through the ages. He praises the ones who ostensibly follow the model of Abraham, courageously arguing with God, and criticizes those he sees as unthinkingly following the law.

Among the meritorious Jewish lawyers, Canada’s own Irwin Cotler gets special mention, with lengthy praise for Cotler’s commitment to human rights for Jews and others.

Dershowitz quotes from a letter he wrote, nominating Cotler for the Nobel Peace Prize. And he dedicates the book to Cotler, “a modern-day Abraham… who boldly confront[s] injustice and who aggressively demand[s] a single standard of justice.”

This book is part of the “Jewish Encounters” series published jointly by Schocken and Nextbooks. I have previously reviewed here the volumes dedicated to Rashi, Hillel, and Yehuda Halevi. All the books in the series are reasonably well written, and most are authored by Jews with some name

recognition.

Unfortunately, none of the books about pre-modern Jews were assigned to authors with expertise in pre-modern Judaism. For some reason, authors of books about the modern period are often genuine subject matter experts.

Dershowitz tries hard to overcome his lack of expert background in classical Judaica. He is, without a doubt, a knowledgeable and educated Jew, and he has relied on a number of research assistants with subject expertise, whose help he graciously acknowledges. He also wisely spends only the first 54 pages of Abraham talking about Abraham.

For those who might wonder if there is enough to write about Abraham to fill more than 54 pages, I recommend an excellent new Hebrew book, Abraham: A Story of a Journey, by a rising Israeli academic and rabbi, Jonathan Grossman, written for both scholarly and lay audiences (566 pages, published by Yedioth Ahronoth Books), a book that builds careful literary readings of the Abraham stories upon expert knowledge of the ancient near east and the rabbinic tradition. I hope it will be translated into English so it can reach a wider audience.

Dershowitz is indeed an expert on the bulk of his book, the survey of Jewish lawyers through the ages. And his references to Abraham and Jewish tradition contain only a few gaffes. One example: Dershowitz presents an English quotation from Maimonides’ Book of Commandments as “translated from the original Hebrew.” Maimonides did not write his Book of Commandments in Hebrew, but in Judeo-Arabic.

READ: WHEN A BOOK (AND A BOOK REVIEW) IS ALSO A FAN LETTER

The attraction of Jews to the study and practice of the law may be traceable in some sense to Abraham, as Dershowitz suggests. At the end of the book he mentions another possibility: “I chose to become a criminal lawyer at least in part because I am Jewish. I was taught from the earliest age that Jews must always remember that they were persecuted and that they must stand up for those who now face persecution.”

Perhaps another reason for Jews’ attraction to the law lies in the centuries-old ultimate Jewish intellectual pursuit: study of the Talmud, which was always seen as a way of coming to understand this world, and God’s blueprint for it. Any synagogue, yeshiva, or school where Jews study Talmud exposes them to contracts, agency, torts, and criminal law from a young age, thus encouraging us to think like lawyers.

Arguing with God, as Abraham did, has a place in Jewish tradition, but much smaller than the place of study of God’s law.