When Alvin Rakoff, the BBC director who discovered Sean Connery, left his home in Toronto’s Kensington Market in 1952 to seek his fortune in television across the pond, he was told to forget it.

“On the boat over, I remember being told quite pointedly that Canadians could never get employed by the BBC,” he said.

But, beating the odds, he got work with the nascent television broadcaster. “Six days after, I sold my first script and I started writing a few things for the BBC, then adapted a major novel for them and then was invited by them to join the producers/directors course.”

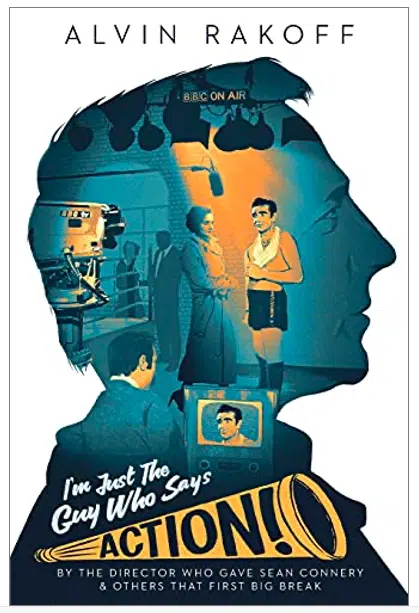

In his recent independently published memoir, I’m Just the Guy Who Says Action, Rakoff tells the fraught behind-the-scenes story of directing his first notable show for the BBC, Requiem for a Heavyweight. It starred Connery.

You don’t have to be a student of early television to enjoy Rakoff’s fast-paced and colourful account of the ups and downs that led to the show’s 1957 broadcast and the rave reviews that followed.

The production’s troubles began at the casting stage. Hollywood actor Jack Palance had played the main character, the boxer Harlan “Mountain” McClintock, in an American production of Requiem. Palance agreed to take the part in the BBC version and a deal was made. Good, easy-peasy, he hought. “Even as a relatively neophytic producer/director, I should have known better,” he writes.

On the Friday before the Monday when rehearsals were to start, he got a call from Palance’s agent. “Jack ain’t gonna make it,” the agent said. “The agent had found something else—by implication, something better—for his client to do. Palance would not be coming over.”

Frantically, he auditioned actors, without success. Jacqueline Hill, an actress with a part in Requiem, also Rakoff’s live-in partner, suggested he audition a bit-part actor, Sean Connery.

The director wasn’t impressed with the audition, but he writes that despite his mumbling Connery was not bad. “There was no escaping that his ability to convey emotion, especially emotion relating to thoughts, was limited. Perhaps, with enough guidance, with enough work from both he and I, a performance could emerge.”

At their first rehearsal, doubts about his choice of Connery began to dissipate. “The words came out clear and strong. Well, reasonably clear. The (American) accent was good. Well, not bad. And we had three weeks to get both better,” he writes.

But trouble was lurking around the corner. Michael Barry, BBC’s head of drama, wasn’t convinced that Connery was up to playing the lead in Requiem. Apparently, someone involved in the production had raised doubts about Connery’s acting ability. Although he was upset about the betrayal, Rakoff decided to stick with Connery.

In his memoir, he writes about the director’s tremendous responsibility during the filming of a live TV show, using the antiquated equipment of the ’50s. During rehearsals for Requiem, he had to calculate which of the four cameras was to be on air at any given moment. So, in addition to scrutinizing the actors, the sets, hand props, costumes, lights and sounds, he was always thinking about the camerawork.

Since television was broadcast live, the unexpected could happen, and when it did, the director had to lead the control room out of disaster.

An interesting thread that runs through the memoir is the story of Rakoff and Hill’s relationship, which like the filming of Requiem, had its ups and downs.

He wanted to direct movies after the success of Requiem, but the leap from TV to film wasn’t easy to negotiate. Not many offers were forthcoming, so he settled for directing Passport to Shame, a picture that has since become a cult classic. It was recently screened at the British Film Institute.

Rakoff still considers it dreck. “It’s a sexploitation movie desperate to get an audience and desperate to make money” he said. “What you learn as a director is that you can’t prejudge how the audience is going to take one of your films.”

It was so low budget that when the lights went out on the set, filming continued, and the dark scene made it into the finished movie. (Passport to Shame can be viewed on YouTube.)

Of the movies he went on to direct, he’s most proud of A Voyage Round My Father (1982), for which he directed Laurence Olivier. Rakoff directed both the television and film versions. In it, a writer, played by Alan Bates, recalls his eccentric blind father, who’s played by Olivier.

“He was meticulous, demanding, excellent as an actor and knew what he had to do and did it, but he was also ill at the time,” he recalled. “He was aging badly and we did one scene where he couldn’t remember the lines or the moves or anything else.”

An assistant thought the footage was unusable, but the film’s editor managed to rescue the scene. (A Voyage Round My Father can also be viewed on YouTube.)

Rakoff has written several screenplays, screen adaptations, theatre musicals and plays. He’s directed and produced many of his plays and screenplays to critical acclaim. He’s also written three novels, including Baldwin Street, based on his youth growing up in Kensington Market.

Born in 1927, Abraham Rakoff was one of seven children who lived in the flat above a struggling store selling general merchandise at 193 Baldwin St., in the heart of the market. Rakoff’s was owned by his father, Samuel, who purchased the stock, and his mother, Pearl, who ran the store.

“You name it, we sold it, as long as it wasn’t edible. Our big reputation as a shop is that we sold sugar bags.”

Rakoff’s sold the bags during the war years, at a time when cotton was in short supply. They bleached the bags and customers sewed them together to make sheets. “Sometimes, the bleaching was bad, and the writing on the bag still remained there. This became fashionable towards the end of the war. People would say, ‘Can I have the ones with the writing on it?’”

The family went bankrupt several times. “My father was always going broke. He was a lousy businessman. He struggled to feed us, and often didn’t succeed. Often the social welfare did help to feed us. We all knew what it was like to go to bed hungry.”

During hard times, he remembers eating onion sandwiches: “All my mother could get was stale bread, given to her by the baker, and rotting onions thrown away by the fruit merchants and she would fry them. And often there was nothing to fry them in, so there were just raw onions and a piece of bread. It doesn’t really alleviate hunger very much.”

As a teenager, Rakoff helped out at home with his earnings from part-time and summer jobs. At 16, faced with antisemitism the summer he worked at Coca-Cola, he changed his first name to Alvin, the first name of the lead character in the movie Sergeant York.

With his summer earnings and with some help from his parents. he paid the tuition to enrol in the University of Toronto. He’d dreamed of becoming a writer, so after graduating with a degree in English, he pursued a journalism career.

However, finding himself unemployed, he and his brother decided to take over the family business. Just before though, he went to New York to take in some shows as a final fling.

But he was so knocked out seeing Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire that he sent his brother a telegram telling him he would fight to get into the world of creativity, whether show business or journalism.

Rakoff landed his first reporting job at the Northern Daily News in Kirkland Lake, Ont., and moved on to other newspapers closer to home, including the Toronto Star.

He did some writing for CBC in the early 1950s. His colleagues encouraged him to go to London to see what the BBC was doing there.

“I told my mother, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll be back in three months at the most,’” he said. “That was 69 years ago.”