I was 28 years old. What the hell did I know about running a network division? I might have been young and inexperienced when I’d started at CBC as a sports producer, but at least I was working in production, so I was in my element. Running a network division would push me into unfamiliar territory—into the worlds of marketing, public relations, acquisitions, scheduling, and contract and sports rights negotiations. It made my head spin to think about it—but of course I thought about it.

I sat to talk things through with Dennis Harvey, the man who gave me my break at CBC. Now head of the network, he was offering me the job he had when he first interviewed me: head of CBC Sports. Also present was Ivan Fecan, the talented programming head of the network. These two network leaders couldn’t have been more encouraging. I accepted the job, and they told me they would announce my appointment the following week, but I wouldn’t start for several months because they wanted my full focus on Seoul.

“The Olympics are too important to us,” Ivan said. “We need to know the Games are in good hands,” Dennis said. This was good to hear—and I absolutely took their point, because even though Canadian networks were able to stand on our own, we were often big-footed by the American networks when it came to sports coverage. In 1988 Canada was 90 percent cabled, but we’d had access to US channels for as long as I could remember. This meant that, while NBC had the exclusive rights to broadcast the Olympic Games in the United States, Canadian viewers were free to choose between our homegrown CBC broadcast and the American broadcast. This was especially meaningful in 1988, because NBC had just won the rights from ABC, so the network was putting an abundance of its resources into Seoul.

There was a lot of talk in the press that summer about how the CBC coverage would stand up against NBC with its deep pockets and overreaching commitment, but I felt confident that we could hold our own. I said as much at a press conference in the run-up to the Summer Games, during which I predicted that CBC’s “David” would get the better of NBC’s “Goliath.” It was a brash, hotheaded thing to say, and I regretted it the moment the words came out of my mouth. The next day the Ottawa Citizen ran a piece on the developing “battle” between the Canadian and American television networks beneath the headline “CBC’s David versus NBC’s Goliath.” I had put a target on our backs, in biblical terms, and I could only imagine how much worse it would have been if I’d made my remarks as president of the network’s sports division instead of as the brash, hotheaded kid in charge of our Seoul coverage.

So that’s the buildup and backdrop to what would turn out to be one of the biggest moments of my career—a reach moment that found me scrambling to cover one of the most heralded Canadian athletes of all time, while at the same time trying to cover my own ass.

We had about 135 people working for us in Seoul. NBC had about 1,500. Our budget was about one-tenth of NBC’s budget. But I never lost sight of my goal: to beat the big boys in the ratings. I’d said at that unfortunate press conference that my strategy in beating NBC was editorial judgment—you know, having our cameras and our crew in the right place at the right time with the right story. A ton of choices fell to me to make in producing the Games: when to go live or play back an event on tape; when to insert a packaged feature or go to the studio for an interview; when to focus on a marquee event of international significance or cover a smaller, under-the-radar event with a Canadian spin.

An important part of my winning strategy was to beat NBC with our coverage of a marquee event on the track-and-field schedule: the men’s hundred-meter sprint. Ben Johnson vs. Carl Lewis—the clash of the titans. Ben Johnson was one of our own and perhaps the biggest star of the Seoul Games. That’s how it often goes in the race for the title of world’s fastest man, but here the hype was particularly intense because everyone was looking forward to a showdown between Ben Johnson and Carl Lewis, who had been the fastest man at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, where he captured four gold medals, including the gold in the hundred meters.

In Seoul, Ben Johnson was like a rock star. Even the Koreans were in love with him. His image was on posters all over town, and we played that up wherever possible. In the lead-up to the big race, for example, I instructed my track producer to let me know the moment Ben stepped into the stadium for his warm-ups so we could cover it live. His every movement was a big deal, because I knew that back home there were viewers channel-flipping between our coverage and NBC’s coverage and I wanted to keep them glued to CBC. I even tried to burn through our commercials early in our telecast so we wouldn’t have to cut away once Ben was on the track doing his thing—that’s how significant it was for me to find a way to beat NBC. I had the NBC feed on in our control room the entire time, so I was constantly aware of what they were doing, thinking of ways we could do things a little differently. When NBC was in commercial and we had a live shot of Ben and Carl warming up on the track, I knew we had an edge.

There’s something to be said about pushing yourself to meet the level of competition, because our track coverage was tremendous—all the way down to our packaged profiles of the shy, stuttering Canadian, whose star was on the rise on his quest to be christened the undisputed fastest man in the world, set against the companion package we’d produced on Carl Lewis, presenting him as this brassy, ballsy American Olympic hero out to defend his gold medal and hold on to the spotlight a while longer.

By the time NBC came out of commercial, our pregame show was in full swing. Our cameras captured the Seoul Olympic Stadium, electric with seventy thousand people cheering their lungs out for an event that would be over in less than ten seconds. When the place fell silent as the runners stepped into the blocks, we captured that as well.

I was about five miles away in our control room at the International Broadcast Center, but I could feel that electricity. I really could. Everyone in our control room was intensely focused on that track, and it was a powerful, gripping thing to be surrounded by so many dedicated professionals with a common rooting interest. As I sat behind my massive intercom panel, which gave me the ability to speak to producers at all the different venues, I felt like a maestro leading a grand orchestra with dozens and dozens of talented people moving to whatever rhythms I meant for us to follow. I’d never worked with a panel so big. But in this moment, I didn’t need the panel. There was only this one race with our Canadian superstar sprinter—regarded as the race of the century. Nothing else mattered.

Ben Johnson’s big thing was his start. We’d spoken about it in our packaged pieces, and it had been highlighted over and over by our analysts and commentators. Sure enough, he exploded out of the blocks like he’d been shot out of a cannon. For a beat it looked like Carl Lewis was right there with him, but then Ben turned on the afterburners and broke away, on his way to another world record. When he crossed the line, he looked off to the side to see who was coming up in his wake, similar to the way Usain Bolt famously crossed the finish line many years later.

Our control room erupted in cheers and mayhem, everyone jumping up and down and clapping each other on the back. It was glorious—one of those moments in the world of sports where you know you’re on the inside of history. The whole time, I kept a dialogue going with our track announcers, Don Wittman and Geoff Gowan, and I remember telling Don what a great job he did on the play-by-play call when he exulted that it was a “September to remember” just after Ben Johnson crossed the finish line.

Our cameras were fixed on Ben as he took his victory lap, draped in the Canadian flag, when I heard a voice in my ear telling me there was a phone call from the prime minister. Brian Mulroney was pretty much the last person I was expecting to hear from in just this moment, but his booming voice was unmistakable.

“What a great moment for Canada,” he said.

I could only agree, while at the same time thinking, This is the prime minister! Talking to me!

He went on to congratulate me on our coverage of the event and to tell me that everyone back home was so proud of Ben.

I started to wonder why the prime minister was calling. National pride is a stirring and boundless thing, and I supposed it was possible that he was just so damn excited that he wanted to connect with someone on site to share in the thrill of it all. But then he got to the reason for his call.

“I really would like to talk to Ben,” he said. “Can you please make that happen?”

I couldn’t think what to say in response—I mean, what the hell do you say to the prime minister? Regrettably, I got a little cheeky with him. I said something like, “You’re watching, right? You see him down there running around with the flag?”

He laughed—that deep, distinctive laugh—and I thought, Thank God he’s laughing.

A couple minutes later, we were able to get a headset on Ben Johnson as he stepped into position with our commentators and we patched in the prime minister for a rousing congratulatory exchange. Everyone in the control booth was beaming with excitement.

It was a great night for Canada, a great night for Canadian broadcasting, a great night for CBC Sports… just, great. Our coverage that night was the highest-rated program in Canadian television history.

In almost every respect, the night was a triumph, but the story didn’t end there.

Three days later, I got a middle-of-the-night call from a source on the Canadian team telling me that one of our athletes had tested positive for steroids. I was groggy, but in my bones, I knew who it was.

“It’s Ben, right?” I said, as if the world’s fastest man and the entire rest of the world were now on a first-name basis. There had been rumours about steroids, and there was no denying that he was jacked.

My source couldn’t confirm my hunch and promised to call me back with additional information as it was available.

I didn’t wait. I immediately called our lead anchor, Brian Williams of CBC (not the Brian Williams, then of NBC) and told him to get down to our studio because we were going on early. It was about 4:30 a.m., but we mobilized. I got our track-and-field broadcast team out of bed to be available to offer commentary. Then I dispatched crews all around the city, hoping our cameras could catch Ben and we could air some exclusive footage to shed even a small shaft of light on a developing story. We sent a team to the athletes’ village, another to the airport, and still another to the hotel where Ben’s representatives were staying.

By the time Ben Johnson’s name was finally and formally attached to all of this speculation, we were good and ready. There hadn’t been time to mourn what we stood to lose as a nation if the story turned out to be true or what it might mean to the sporting world at large. There was a much larger conversation still to be had about what these allegations (and, potentially, these revelations) might mean to these Olympic Games. My sole focus was getting to the heart of the story and making sure we had it covered from every possible angle. And we did. We had Ben at the airport trying to leave the country. We had his agent vehemently denying the charges and claiming that the sample vials had gotten mixed up. We had the leader of the Canadian delegation talking about what a sad day it was for our athletes and for our country.

The spirit of collaboration permeates the International Broadcast Center at the Olympics. Everybody had television monitors showing what the broadcasters from other countries were doing, and we wound up sharing and trading a lot of footage because we weren’t really competing with each other; we were all in the trenches together, in pursuit of the same goal. If I needed, say, specific footage of Sergey Bubka, the Ukrainian pole vaulter, I could talk to my Russian friends and see if they had it. As the morning wore on and our colleagues started to notice what we were doing on this Ben Johnson story, the global broadcasting community descended on our stage. Our phones were ringing off the hook, and foreign broadcasters were lining up at our door. We, of course, wanted to accommodate every request, but in those pre-digital days we had to dub the tapes manually and pass them along one at a time. We were literally throwing the tapes out the door as soon as we made a new copy, just to feed all these broadcasters.

Somewhere in the middle of that madness, I looked up and realized we’d been on this Ben Johnson story for a long time. We’d stopped covering the rest of the Games altogether. I always believed in the maxim that shows about sports never do as well in the ratings as the sports themselves. I never wanted to be away from the action for too long.

I wasn’t the only one who believed this. Laurence Kimber, one of my early mentors at CBC, came into the control room in a panic. “Arthur, you’re making a big mistake with this Ben Johnson thing,” he said. “You’ve done a great job, but enough is enough. You need to get back to the rest of the Games.”

It wasn’t just Laurence trying to bring me back to our scheduled coverage. There were a lot of folks in our control room and in my headset telling me the same thing, reminding me why we were there, but Laurence’s appeal stands out in my memory. He was right—but I had a different take. I respected Laurence a great deal, but this was the biggest story in the country. It was bigger than the Olympics. It could not be ignored or set aside. We had a spirited argument right there in the control room, in front of everybody, but in the end it was my call to make, so I kept at it.

Before I could convince myself that I was doing the right thing, the red phone rang in the control room. The red phone was like our “Batphone”—it connected me directly to the head of the network back home, Dennis Harvey. The guy who took a chance on me and gave me a break at CBC Sports and most recently offered me the job as head of CBC Sports. The red phone almost never rang, so I briefly froze when it sounded, my mind racing to the many decisions and moving parts I’d been making and juggling that morning. Not only had I stopped covering the Games, but I hadn’t gone to commercial in 90 minutes. I could only think that I was about to be chewed out for losing sight of our bottom line. Ad buys during the Olympics are among the most expensive in television, and here I had ignored our high-end advertisers. In the flash moment between the first peal of the red phone and the second half peal when I answered it, my heart raced.

“I know, I know,” I said before Dennis had a chance to even speak. “I haven’t gone to commercial.”

“Don’t worry about it,” Dennis said. “We’ll make up the commercials. We love what you’re doing. You’re making the right call.”

I think I actually let out a phew! As my sigh of relief at this report from Dennis resonated around our control room, everyone on our Seoul team sighed right along with me.

Eventually, we got to a point where there wasn’t much happening on the Ben Johnson front, and we turned our attention back to the Games. But the full day after the story broke was again dominated by news coverage as it became clear that Canada’s Olympic hero would be stripped of his gold medal. To this day I can close my eyes and picture a shot we grabbed of an IOC official removing the number one from Canada’s tally from the medal leaderboard. It was such a powerful, painful moment presented in such a quiet, somber way, and it stands in memory as a symbol of the highs and lows of those Games, and the artistry we tried to bring to the storytelling.

Our coverage continued into the evening, and I didn’t leave my chair the entire time, except for a bathroom break. It was the most draining, wrenching experience of my career—and, in some ways, the most fulfilling. I was so exhausted I passed out in the control room the following day, right around the time Wendy arrived in Seoul to spend a couple days with me and enjoy the Olympic experience. In fact, as soon as she got to the broadcast centre, the on-set doctor sent me back to my hotel room to recharge, because I was clearly thrashed. I hated giving up the reins like that, and I hated that Wendy had flown halfway around the world to spend some time with me and I was so completely out of it, but the work had taken its toll.

When we got back to the hotel room that night, Wendy read me a fax from Dennis Harvey and Ivan Fecan: “On Friday, it was the best of times. Last night, it was the worst of times. But through it all, you guys were magnificent.”

The Ben Johnson steroid drama gave the lie to that old adage about how no pregame (or postgame, in this case) show beats the game itself. In the end more Canadians watched Ben Johnson lose his gold medal than watched him win it—and of those people, more people watched on CBC than anywhere else. In Canada, we ended up beating NBC in the ratings by a ten-to-one margin, the greatest domination of homegrown coverage over US coverage in the history of Canadian television. So on the back of these unfortunate events, I was able to back up my David vs. Goliath boast—not exactly the way I wanted it to happen, but it happened just the same. More than that, our coverage was praised and highlighted in newspapers and magazines across the country—all over the world, even.

Months after the Games, I was invited to the US Olympic Academy in Olympia, Washington, to discuss our methodology in covering the Games and the surprising number of Americans living in border cities who were watching CBC over NBC. And to cap it all, at the end of the year, we were awarded two prestigious Gemini Awards, our Canadian version of the Emmy—one for Best Sports Event for our overall coverage and one for Best News Coverage for “Ben Tests Positive.”

Still, I came out of Seoul with mixed emotions. As a sports fan and a Canadian, it was depressing as hell to see Ben Johnson’s legacy come apart. Really, it was a killing, dispiriting thing, to see Canada’s favorite son diminished in this way. As a producer, however, I thought our team did an outstanding job. Our coverage was without peer, so there was something to celebrate here as well. There was joy and validation in this moment—and an emotional reminder that sometimes you have to jump on the runaway train and hang on for dear life until you figure out where it’s going.

The reach here came in throwing away the script and doing what I thought was right, even as those around me were telling me different.

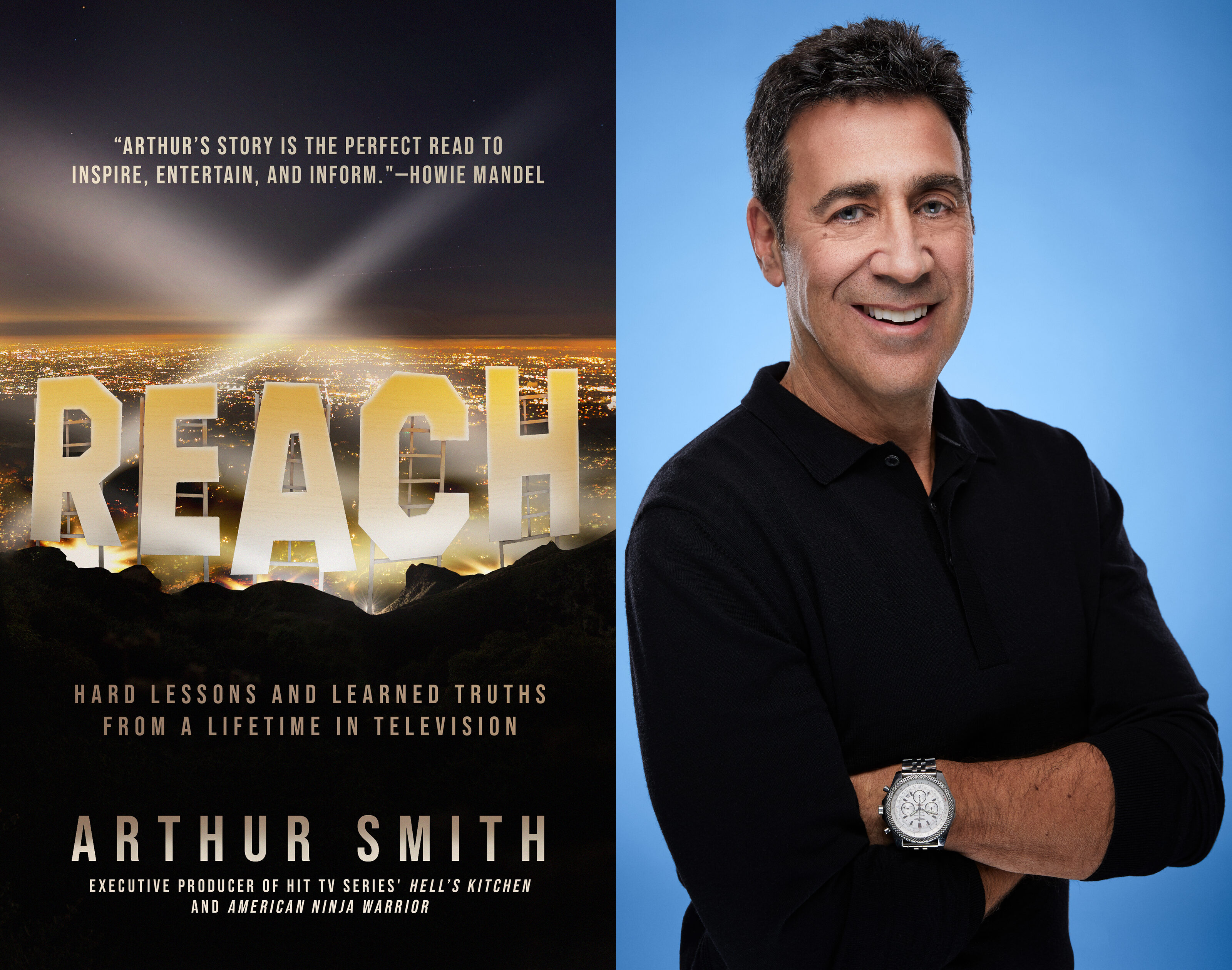

From Reach: Hard Lessons and Learned Truths from a Lifetime in Television by Arthur Smith. Used with the permission of the publisher, Blackstone Publishing. Copyright ©2023 by Arthur Smith.